16.4 War’s end: commemoration and creating a legend

How the war ended: the war front

By November 1918, the Great War was in its fifth year. Soldiers talked mockingly of it continuing for decades. British military planners calculated that it would not end until 1919 or 1920. Its sudden conclusion took most people by surprise.

One by one, Germany’s allies surrendered: Bulgaria in September 1918, Turkey in October, and Austria in early November. An armistice followed that took effect on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918.

During World War I, the German-sounding names of approximately 80 Australian towns, mostly in South Australia and Queensland, were changed. For instance, Rossler in Queensland became Ambleside, Mueller Park in Western Australia became Kitchener Park, Bismarck in Tasmania became Collins Vale, Germantown in Victoria became Grovedale and German Creek in New South Wales became Empire Vale.

On most fronts, the roar of gunfire stopped at 11 a.m. An eerie, unfamiliar silence followed.

An American pilot, looking out over the trenches from his plane, then saw helmets and guns flying into the air and men waving to each other across no-man’s-land.

When the war ended there were around 90 000 Australian soldiers at the Western Front. More than 60 000 others were in Britain in hospitals or at training depots, and another 30 000 were in the Middle East. By September, 11 of the 60 AIF battalions had already been disbanded due to lack of reinforcements. The Australians composed less than 10% of the British Army, but in the final stages of the war they had won many victories, liberating 116 villages and towns and capturing nearly one-quarter of the German prisoners and guns taken by the British.

Bringing the troops home

The task of bringing Australia’s fighting men home was a monumental one. At war’s end there were up to 185 000 troops on service in France, Belgium, Egypt and Mesopotamia. As well, there were around 5000 munitions and other war workers in Britain, 4000 sailors in the Royal Australian Navy and another 3000 in the Australian Flying Corps. Additionally, there were still almost 1500 Australian nurses abroad, serving in many places, including India and Italy. All told, around 200 000 Australians had to be repatriated, along with 15 500 wives and children of Diggers who had married abroad.

Lieutenant General Sir John Monash, who had performed so outstandingly in the war’s closing phase, was placed in charge of repatriation and demobilisation. He acquitted himself magnificently in this task as well. Huge numbers of soldiers who were no longer engaging an enemy could easily become a serious disciplinary issue. There were riots involving Australians at a French general hospital and a military prison in mid-November 1918, just days after the Armistice. There was also determined strike action by the 5th Divisional Artillery against a heavy application of military regulations. The Surafend tragedy in Palestine, mentioned earlier, occurred in December.

There were more than 900 Australian deserters on the loose behind the lines in France when the war ended. Twenty years later, around 750 were still unaccounted for.

Then, when the ships arrived back in Australia, there was a new problem. A global pandemic of ‘Spanish influenza’ was now raging and killing huge numbers of people – in fact, 20 million to 30 million across the world. Soldiers returning home spread the virus across the world. It first reached Australia in January 1919, leading to considerable concern and mass panic. As a result, troop ships were often quarantined on arrival and the men prevented from landing, which led to numerous disturbances. In this manner, the epidemic was more contained here, although 12 000 lives were still lost.

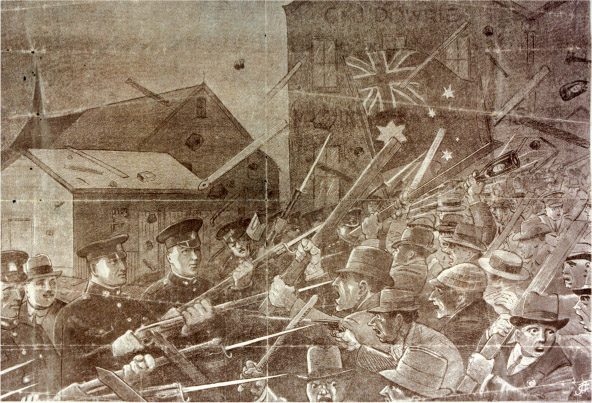

The men who returned home were not the same people who had left to fight. Even those who were not physically injured were often psychologically damaged by what they had seen, experienced and done. They tended to be unstable and volatile. During 1919 and 1920, research has now uncovered around 20 major riots in Australian cities involving returned soldiers, as well as higher levels of domestic violence in Australian homes.

Australians were extremely proud of their fighting men, but they were also wary and alarmed by their unexpected home front behaviour. They seemed to represent a new, unpredictable force in Australian society.

When the ‘original’ ANZACs – those who had enlisted before Gallipoli – returned home on furlough in September 1918, there were only 7000 to 9000 still in the fighting ranks, out of 32 000 who had first gone to war.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 16.13

- Explain the operational difficulties involved in bringing home the surviving soldiers, sailors, airmen, nurses and munitions workers after the war.

- Discuss why it was so difficult for the authorities to discipline and control the Australian soldiers.

- Investigate the troopship disturbances caused by the Spanish influenza pandemic.

- Examine the effect of the Spanish influenza pandemic on Australia. Compare it with the outbreak in other nations.

Repatriation and grieving

Until early 1918, it was thought that the private patriotic funds could look after the needs and problems of returning soldiers. Help was therefore seen more as a charity than a right. Yet, with the numbers of damaged men rising alarmingly, the Hughes government rather reluctantly agreed in March 1918 to establish a Federal Repatriation Department to help rehabilitate war veterans, and aid them with housing and retraining for nonmilitary employment. War pensions for the families of the dead and for disabled men, along with the necessary medical services, were also required. Later, in 1935, service pensions for ‘prematurely aged’ and ‘permanently unemployable’ ex-soldiers and warfront nurses were introduced.

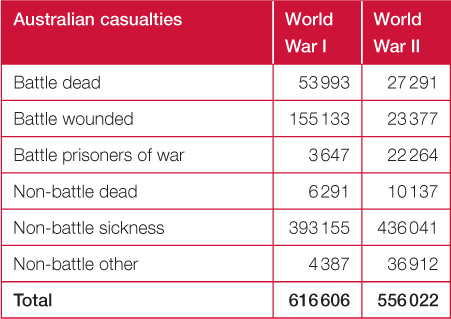

The casualties of war continued mounting after the guns ceased firing. In the book, Australians, an Historical Atlas, there is a remarkable table that includes, along with the war dead and injured, the numbers who fell ill due to warfront conditions (see Source 16.15). Sickness adds a further 393 155 casualties to the already growing list, resulting in an extraordinary total of 616 606 cases of war-afflicted men. Remember that around 417 000 men had enlisted and 332 000 had fought. So, in total, Australia’s most comprehensive casualty list for World War I considerably overshadows its full enlistment total.

| Australian casualties | World War I | World War II |

|---|---|---|

| Battle dead | 53 993 | 27 291 |

| Battle wounded | 155 133 | 23 377 |

| Battle prisoners of war | 3647 | 22 264 |

| Non-battle dead | 6291 | 10 137 |

| Non-battle sickness | 393 155 | 436 041 |

| Non-battle other | 4387 | 36 912 |

| Total | 616 606 | 556 022 |

Source 16.15 Australian casualties: World War I and World War II. Particularly, note the numbers of wounded and sick.

This presented a formidable challenge for repatriation services. Though not all needy ex-servicemen sought assistance, by the 1930s, up to 80 000 incapacitated ex-soldiers were receiving a pension. The number rose to over 283 000 in 1931 when widows and children of the deceased, plus wives and mothers caring for limbless and other disabled veterans, were added.

Unlike the United States, which was closer geographically to Europe and had fewer casualties, Australia did not bring its war dead home. There are about 35 600 deceased Australian soldiers buried in more than 50 cemeteries in France and Belgium. There are another 2848 lying underground at Gallipoli and others again buried in Egypt and Palestine. Additionally, the Australian War Memorial at Villers-Bretonneux in France provides the names of a further 10 892 men killed on the Western Front whose bodies were not recovered. A vast collective sadness flowed across the land, taking up residence in most of its homes. Historian Michael McKernan aptly named these after-war decades ‘The Grey Years’.

Returned soldiers often found great difficulty in adapting back into civilian life. They and the society they re-entered had both been harshly transformed. The soldiers’ warfront sufferings were unimaginable to civilians. Communication broke down. Marriages often dissolved in quarrels and violence. Crime rates rose. Fears were expressed that city-gatherings of ex-soldiers could lead to serious disturbances – and they often did. The veterans’ mood was volatile.

The Soldier Settlement Scheme, one of the central plans of the repatriation program, therefore attempted to remove returnees from urban areas into more dispersed agricultural regions. Unfortunately, it was a poorly conceived and administered venture. Men carrying the scars of war often made poor farmers and the land was often badly chosen. Debts accumulated and most of the farms failed with many tragic results. Sadly, this was one war for which there were few happy endings.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 16.14

The cost of annual war pensions in 1931 was £8 million (or around $1600 million in today’s currency). This was almost equal to half the entire Commonwealth budget when the war began.

Growth of returned soldier organisations

From mid-1916, Australian returned soldiers began organising to defend their rights and future welfare. The first groups emerged from soldiers’ club rooms in many Australian cities, which were havens for the wounded and invalided men. Here they met with others who had shared similar experiences and truly understood what warfare meant. As members of one such organisation, the Returned Soldiers Labor League, stated: ‘The undying gratitude which the returned man has earned is gratitude and little more’.

Between 1916 and 1919, a range of such groups was established, spreading over the entire political spectrum. On the conservative right were such bodies as the Returned Soldiers and Patriots National League. Further to the left, they included the Returned Soldiers Anti-Conscription League and the Australian Comrades of War.

From this confusion of contesting groups, the organisation we know today as the RSL (Returned & Services League) eventually emerged, by around October 1918, as the official association representing returned men. The RSL enjoyed official endorsement and funding, and had the advantage of recruiting members on the returning troop ships before they docked in Australia.

Although the RSL depicted itself as a non-political organisation that defended the welfare needs of veterans, it tended to adopt a distinct range of positions. It strongly supported the British Empire, the White Australia Policy and an active defence policy. It maintained a forceful anti-German position for a considerable time and tended to regard all non-British ‘aliens’ with suspicion. It also opposed militant trade unions and left-wing activists. The RSL declared its intention to ‘resist revolution by force’. Thus, it was a strong advocate of conservative values and a vigilant defender of the status quo.

During 1919, the RSL was attracting ex-soldiers at the rate of a thousand per week, and by year’s end had reached a strength of 150 000 members. During the 1920s, however, its numbers went into serious decline, bottoming out at around 24 000 in 1924 – or only 9% of returned men. Feelings of disillusionment and a general turning against warfare during the 1920s may have had much to do with this. Numbers slowly recovered as Australian politicians began actively promoting ANZAC Day in a disunited society. Membership rose from about 50 000 in 1930 to almost 80 000 in 1936. The RSL badge became a powerful symbol of political pressure, and was stronger than that of similar veterans’ groups in the other Allied nations.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 16.15

- Outline why returned soldiers felt the need to band together.

- Explain how the RSL emerged as the sole returned soldiers’ league.

- Identify the ways the RSL supported the needs and demands of war veterans.

- Describe what other values the RSL supported.

- Describe the role returned soldiers played in the resistance.

- Recall why RSL membership declined in the 1920s.

How ANZAC Day began

Queensland was called ‘the most disloyal state’ during the war by the Commonwealth authorities.

Yet it was here that the idea to commemorate the Gallipoli landings of April 1915 as ‘ANZAC Day’ began. It was the brainchild of Thomas Augustus Ryan, the son of a Bathurst grazier. He spoke of it to the State Recruiting Committee in late 1915.

Ryan’s only son, Gus, was fighting with the 5th Light Horse at Gallipoli. It was believed that marking the event with church services, a street march and patriotic speeches might establish ‘a solemn day in memory of the baptism of blood’. It might also encourage more men to enlist.

Evacuation from Gallipoli began on 18 December 1915 and ended on 8 January 1916.

Several days later, a meeting in Brisbane, prompted by Ryan’s suggestion, was attended by Queensland’s Governor, the Premier, the Inspector-General of Commonwealth Forces, the Mayor of Brisbane and other leading opinion-makers.

It was here decided that ‘the heroic conduct of our gallant Queensland troops’ should receive ‘undying fame’. The Queensland 9th Brigade had been the first ashore at ANZAC Cove. Follow-up meetings by educators and Empire loyalists, with Queensland’s Labor Premier acting as Chairman, organised the details, including a complementary ceremony to be held at Westminster Abbey in London, and invited other Australian states to join the commemoration.

After church services on the morning of 25 April 1916, 50 000 Brisbane citizens attended the first ANZAC Day march. The Brisbane Courier said it was the biggest crowd ever assembled in the metropolis. The surging mass of people was ‘almost uncontrollable’ at the saluting base in front of the General Post Office and several women fainted in the crush. The Daily Standard newspaper added that many people were ‘dressed in mourning’ and carried ‘some cherished relic … associated with one or another of those sleeping at Gallipoli’. Around 5000 purchased the first ANZAC Day badges, depicting the winged lion of St Mark (‘a symbol of super-human strength’) along with the Queensland crest and motto, ‘Brave yet Faithful’.

Around 6430 soldiers marched that day, most of whom were fresh recruits. They were greeted with hearty cheering, but this fell away to a silent hush as the ‘pathetic figures’ of wounded and disabled returned men who could not walk were carried from 20 motor cars onto the saluting platform. Speakers claimed that the ‘greatest military event in Australian history’ had allowed the nation ‘to find its soul’.

Meetings that evening and over subsequent days were devoted to encouraging more able-bodied men to enlist. The battle of Fromelles was only 3 months away. In Sydney, around 700 recruits staged an unauthorised march, watched by huge crowds at the Domain. Tasmania did not mark the occasion until 3 days later. In this manner, ANZAC Day began in Australia. Its future history was to be a most variable one.

In 1922, the RSL opposed the burial of an ‘Unknown Soldier’ in Australia, arguing that ‘the sentiment of the Empire was expressed in the burial in London’. An Australian ‘Unknown Soldier’ was not buried at the Australian War Memorial’s Hall of Memory until November 1993.

Developing the ANZAC legend

The ‘spirit of ANZAC’ is said to provide the foundational cement for Australian nationalism.

Yet the commemoration itself did not become a single national event until 1930, 15 years after the ANZAC Cove landing. Before this time, ANZAC Day was differently observed in the various states. In some, such as Western Australia, it was a holiday. In Queensland, it was not. Certain states allowed other entertainments, including racing and gambling, on the day. Other states enforced a more solemn, religious-like observance.

In 1927, after Melbourne had declared a holiday on the day, 28 000 people joined its march, but in Sydney only 4000 paraded, while 1600 marched in Perth. It was only when state and federal politicians and church leaders joined the RSL in promoting the occasion nationally in the late 1920s that it emerged as a leading national day. ANZAC Day, therefore, was arguably as much a political creation as a spontaneous people’s event.

ANZAC Day during the 1930s settled into a regular pattern of morning church services followed by a solemn march, and then an afternoon of drinking, sporting events and two-up games – much as soldiers had behaved at leisure on the Western Front. In 1938, for instance, ex-soldiers played two-up in the main streets of Sydney. They danced, sang wartime songs, staged mock marches and directed traffic.

World War II (known as ‘the Good War’) increased ANZAC Day’s popularity, but by the late 1950s it was again being criticised for promoting military values and drunkenness. This was dramatically shown in Alan Seymour’s 1960 play, The One Day of the Year, which caused great controversy.

Indifference and hostility grew during the Vietnam War years, as the march became a focus for anti-war protests. In 1973, the Australian Labor Party even discussed changing the ANZAC Day format into a celebration of peace. With civilian casualties again mounting in global warfare, feminists attempted to join the march in the early 1980s to remember the female victims of war, leading to clashes and arrests.

Since 1990, however, when Prime Minister Bob Hawke visited Ari Burnu cemetery at Gallipoli, ANZAC Day has been revitalised, with annual pilgrimages to ANZAC Cove and the Western Front. Following this, Prime Minister Paul Keating suggested in 1993 that the 1942 Kokoda campaign in New Guinea, where Australians fought more to defend their homeland than for Britain, should be revered above Gallipoli. Finally, in the years of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, both Liberal Prime Minister John Howard and Labor Prime Minister Kevin Rudd began recasting the mood of ANZAC Day less as one of commemoration of soldier sacrifice and regret about war’s cruelties and more as one about celebrating Australia’s long military tradition. Each generation, it seems, moulds the ANZAC story to its immediate needs.