16.3 War on the home front

Censorship and propaganda

Soldiers and airmen who fought in or above the trenches and across Middle Eastern deserts experienced the harsh realities of warfare at first hand. Those who had stayed behind on the home front, however, understood the war mainly as a series of highly manipulated images.

Official censorship was imposed from the moment the war began to ensure that the Australian public rarely, if ever, learned how the fighting was really progressing. Unpleasant realities were blurred or blanked out. Realistic images of warfare or of wounded and dead were banned. Such censorship was particularly strong in Australia. The War Precautions Act imposed these regulations upon the 1843 Australian newspapers and magazines, as well as on all films made locally or abroad. Soldiers’ letters and postcards were heavily censored and troops were forbidden to carry cameras to the front. Military censors, stationed at post offices, even intercepted and censored suspicious civilian correspondence.

A mass of officially produced propaganda created false images both of warfare and the nature of the soldiers themselves, whether Allied or enemy. Military defeats were often presented as victories, or not reported at all. Terrible carnage was simply glossed over. For instance, after Australia’s single worst troop losses at Fromelles on 19 July 1916, all that people back home read in their daily newspapers was that the Australians broke into the German trenches, stayed there for a while and then came away, bringing around 140 prisoners with them. There was no mention of the 5000 Australian casualties.

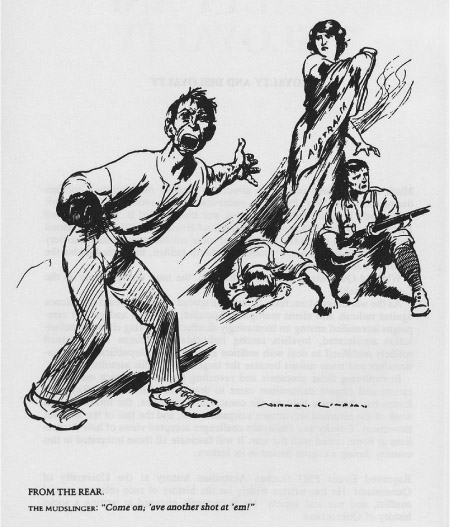

While propaganda downplayed the horrors of war, it also exaggerated the alleged frightfulness of the enemy. Germans were depicted as beasts, capable of any atrocity. In Australia, the artist and cartoonist Norman Lindsay produced some of the most lurid Allied cartoons, depicting German soldiers as massive, ape-like monsters wearing spiked helmets, their hands dripping with innocent blood.

Taken together, censorship and propaganda were continuously applied to boost civilian morale, encourage men to enlist, suppress the horrors of war, protect national security and present the Allies as heroic crusaders and the enemy as savage brutes. Civilians, therefore, did not know or understand the real war the soldiers endured.

The first song ever banned by an Australian government was called ‘I didn’t raise my son to be a soldier’, which was widely sung at anti-war rallies in 1915.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 16.8

- Conduct a class debate on the value of censorship and propaganda in wartime. Should they be regarded as a benefit or liability?

- Investigate the Australian War Precautions Act of World War I. What were its main features and how was it implemented?

- Assess how effective censorship and propaganda were in the manipulation of public opinion. Do you think people realised their understanding was being manipulated?

Loyalty and disloyalty

Many Australians remained unwavering in their loyalty to the British cause throughout the entire war. Affection for Britain was strong. Most Australians had direct family ties with the British Isles and often called Britain ‘the Motherland’ or even ‘Home’. For example, the Lewises were a respectable, affluent Melbourne family who believed fervently in the righteousness of the Allied cause. By early 1916, four of their seven sons had enlisted. Two of them were invalided home as shambling wrecks with fever, injury and shell shock. A third was killed in action on the Western Front after twice being severely wounded. In his memoir Our War, Brian Lewis, the youngest son, charts the family’s searing grief and increasing disenchantment with the war. He reveals the tension in loyalist households between a belief in the ‘winnability’ of a ‘just war’ and the slow realisation of its injustices and appalling costs.

There were others – a small, outspoken minority – who opposed the war from the start. Some were Quakers and secular pacifists who opposed international violence on principle.

Others were eugenicists who argued that war destroyed the nation’s healthiest specimens, thus causing social degeneration.

Still others were internationalist socialists who believed that the world’s workers should unite rather than destroy each other, arguing that the workers’ true struggle was against the abuses of capitalism. It was winning that sort of battle that really advanced freedom and democracy in any society, not fighting fellow workers in foreign wars.

The message of such dissenters was muted by official censorship but, as the war dragged on, more people were persuaded by it. The return of wounded, gassed and distraught men from the front also shocked the Australian public.

Gradually, a feeling of war-weariness – and a growing war opposition – spread through Australian society. Loyalists attacked anti-war activists in the mainstream press, the Protestant churches and the parliaments, branding them as traitors who were working in harmony with the enemy. Social division and polarisation increased dramatically from 1916 onwards. The war was splitting the nation into the ranks of ‘loyal’ and ‘disloyal’, rather than unifying it under the banner of ANZAC.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 16.9

Military conscription: the first attempt (1916)

The struggle over military conscription in 1916 and 1917 was one of the most dramatic conflicts in Australian history. Few today can grasp how bitterly this contest was fought by opposing sides, each of whom believed that their cause was both righteous and vital to the nation’s future.

Those who supported conscription claimed that only military compulsion could now force fit Australian men to the fighting front in sufficient numbers to win the war and prevent a German takeover of British territory.

Those who opposed it argued they were fighting for the democratic right of free choice and to prevent the spread of military tyranny into the workplace. They claimed that Australia had already done more than its fair share and that conscription would drain away all its manpower.

By May 1916, Britain had introduced universal military conscription for all eligible males and it was expected that Australia would soon follow.

Local volunteering was falling away, despite the most determined recruiting efforts to encourage men to enlist. Between December 1915 (when the Gallipoli withdrawal occurred) and May 1916 (when Australian troops began fighting in Europe), the reinforcement numbers required had fallen short by around 47 000.

By early August 1916, Labor Prime Minister William Morris Hughes began pressing for conscription. Many in the Australian Labor Party, however, strongly opposed the idea. Before the year was over, the party, federally and in most states, was split over the matter.

It was the greatest political schism in Labor’s history.

The issue was put to the people in the form of a referendum. The campaign to encourage voters to decide on ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ extended across September and October 1916. It came in the wake of the loss of 27 000 Australians in 7 weeks in the terrible Somme campaign.

The campaign was waged in an atmosphere of extreme tension and hysteria. Appeals to women by both sides were particularly emotional. In many centres, there were heated encounters and episodes of street violence. Enormous rallies were held by both sides, and arguments grew more extreme and irrational. Pro-conscriptionists, led by Hughes, claimed that members of the anarchist group, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), were planning to burn down the city of Sydney.

Twelve of its leaders were sent to prison for long terms after a widely publicised show trial.

Polling day was 28 October. Although voting was not compulsory, 82.8% of the electorate voted. When the votes were counted, it was found that, out of 2 247 590 cast, there was a slim ‘No’ majority of 72 476 (or 3.2%). Victoria, Western Australia and Tasmania had voted ‘Yes’, while New South Wales, Queensland and South Australia had voted ‘No’. Conscription for the time being had been defeated, but the matter was not yet over.

Military conscription: the second attempt (1917)

In November 1916, New Zealand introduced military conscription and in 1917 Canada and the United States followed suit. In the same year, Australia mounted a massive national recruitment drive, using every conceivable method to pressure men to enlist. It was now calculated that the nation needed to produce 5500 to 6000 reinforcements per month to replace these casualties and to prevent the Australian 4th Division being broken up and dispersed among the other British ranks. By the last quarter of 1917, however, the average monthly total of recruits was only around 2500, or less than half the number required.

The year of 1917 had also been a tumultuous one on the home front. The failure of the first conscription referendum was denounced by Prime Minister Hughes as ‘a black day for Australia … a triumph for the unworthy, the selfish and treacherous’. In November 1916, he had quit the Labor party with 23 other parliamentarians who later merged with the Liberals to form the National Party. During a federal election in May 1917 the Nationals, depicting themselves as the ‘win-the-war party’, had won a decisive victory, heavily defeating Labor.

Though Hughes had promised during his campaign not to ‘attempt conscription … during the life of the forthcoming Parliament’, his outstanding win encouraged him to try a second referendum in November and December 1917.

The second conscription referendum was even more disorderly than the first. The historian Joan Beaumont writes of violence at levels rarely seen in modern Australian politics. There was uproar when the federal government closed the polls only 2 days after announcing the campaign, thus disqualifying many itinerant workers who would need to re-enrol. Australians with a German-born father were also stopped from voting. Official censorship was applied to the ‘No’ campaign in an even more heavy-handed way than before.

Despite all these tactics – or perhaps because of them – the second referendum failed more decisively than the first. On 20 December, the ‘No’ majority was 166 588, or 7.6% of the valid votes. Victoria joined New South Wales, Queensland and South Australia in opposition, while Tasmania now only supported the proposal by 279 votes. Australia had been the only country to try to introduce conscription by democratic means and remained one of the few combatant nations to support a voluntary enlistment system throughout the war.

The wording of the second referendum question was made deliberately obscure. The question read: ‘Are you in favour of the proposal of the Commonwealth Government for reinforcing the AIF overseas?’ The word ‘conscription’ was not mentioned.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 16.10

Select two opposing teams of speakers: one team to support the pro-conscription case and the other to argue against conscription. After the debate, get the class to vote by secret ballot, either for the ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ position. Tabulate your votes to see where your class would have stood in the great controversies of 1916 and 1917.

Through further reading, attempt to discover how different groups in Australia voted on the conscription issue; for example:

- Protestants and Catholics

- working-class and middle-class people

- women and men

- British-born and Australian-born people

- rural and urban Australians.

Australian women and the war

In wartime Britain there were dramatic changes in the economic role of women. An extra 800 000 women entered the paid workforce, where they became, for instance, tramway conductors, van drivers and milk deliverers. By 1917, over 800 000 women worked in the munitions industry alone.

Much of this change occurred because eligible British men were conscripted into the trenches.

In Australia, however, where military conscription was defeated – and where there was no local munitions industry of any size – the change in women’s economic position, even in the short term, was not so marked. Most women workers were clustered in the worst paid jobs, and received less than half the wages of men.

Nonetheless, with more than 400 000 males enlisting, more women became clerical workers, entering the banking and insurance industries as well as the public service. Some women became police officers for the first time and there were calls for more female medical officers and lecturers. Many of these jobs were lost, however, when men returned from the war.

During World War I, a vast grief and sense of bereavement gradually spread across the nation as men left to fight and women stayed behind and waited. This waiting created huge anxieties, as mothers, sisters, wives and female companions worried continually about the fate of each absent male.

A relatively small number of women, however, did serve on or near the fighting fronts. Around 2060 became nurses who tended the war wounded, while others served as doctors and medical orderlies. These women therefore experienced the realities of war in a most intimate manner.

One of them, Sister Alice Kitchen, described in her diary attending hundreds of dirty, hungry and ragged wounded men aboard the underequipped hospital ships standing off Gallipoli. Another, Alice Williams from Queensland, later wrote:

When I remember how well and strong our boys were … how full of hope and cheer … I am sad, for I also remember how we brought them home again … maimed, wounded, gassed, crippled for life, and some did not return.

Some women on the home front, who initially had little idea of such realities, took a leading role in shaming men into enlisting. This behaviour was particularly marked when the war began and during the great recruiting drives of 1916–17.

Other women joined rifle clubs and indulged in military drilling. Many helped to raise money for patriotic funds or knitted socks for the soldiers. There were also women of pacifist and socialist beliefs who campaigned strongly against the war. Arguing that a woman’s role should always be a nurturing and life-preserving one, they formed such organisations as the Women’s Peace Army.

Their meetings were often disrupted by angry returned soldiers and other loyalists. These activist women also led demonstrations, particularly in Melbourne, against the fast-rising cost of living, especially of food for their children. During August and September 1917, these marches became violent when police intervened. They sometimes turned into shop-window-smashing food riots.

![Source 16.11 Australian schoolgirls knit socks for soldiers at the Western Front [AWM/H11581].](https://www.cambridge.edu.au/go/epub/library/Humanities9/OEBPS/images/Chapter16/9781107654693_1724.jpg)

Yet overall, women’s roles changed far less in Australia than in Britain because of the war. Women in Australia had already cast a national vote since 1902; and their move into wartime work, previously restricted to men, was far less dramatic than in those countries that had introduced military conscription for all eligible males, leaving many more job vacancies.

One of the leading anti-war campaigners in Australia was Adela Pankhurst, a daughter of the British suffragette, Emmeline Pankhurst. Adela was arrested numerous times for her activism and Prime Minister Hughes attempted unsuccessfully to have her deported.

Indigenous people and the war

Learning the full story of Indigenous servicemen in World War I is a work still in progress. It remains unclear how many actually served. Several years ago, the figure given was usually 300 to 400 men.

Today, the Australian War Memorial believes that up to 800 may have been involved.

This is because many of the Indigenous men who fought could only enlist by hiding their Aboriginality. The Commonwealth Defence Act 1909 prevented any male who was not ‘substantially of British descent’ from enlisting.

Thus Indigenous men had to ‘pass for white’ and tended to join up on a ‘don’t ask; don’t tell’ basis.

Many were barred from the services, especially in the early stages of the war. Later, as the demand for recruits became more desperate, regulations were somewhat relaxed. Following the failure of the 1916 conscription referendum, it was decided that part-Aborigines (called ‘half-castes’ at the time) could be accepted if the examining medical officer was satisfied that one parent was ‘of European descent’.

These restrictions point to the highly racist nature of Australian society at this time. Indigenous people had very limited rights. Mostly, they could not vote or own land or other property. Their civil liberties were severely restricted and they were being forcibly moved onto reserves and missions.

Their families could be broken up and children taken at will. All this was a result of their thorough dispossession in Australia, during which many Indigenous men had died fighting for their homelands.

Why, then, would young Indigenous men decide to fight for the British cause in World War I? After all, it was the British takeover of Australia that had created most of their difficulties. Yet Australia was still primarily their land and many joined to fight for it. Furthermore, military pay was very enticing, as was the prospect of leaving behind oppressive conditions at home and seeing some of the outside world. Some may have thought that fighting and sacrificing alongside other Australian men would lead to an improvement in their racial plight after the war.

Many who fought came from Queensland, but lists have also been compiled of 165 Indigenous men from New South Wales, 68 from Victoria and 45 from South Australia. Indigenous men also enlisted from Tasmania, especially from the Bass Strait Islands. One was John Miller, the grandson of Fanny Cochrane Smith, an Indigenous Tasmanian woman whose voice is preserved singing on one of our earliest recordings. Miller was killed in the Gallipoli landing. Five Indigenous men are presently known to be buried at ANZAC Cove.

Many Indigenous servicemen fought on the Western Front and around 118 served in Egypt and Palestine in the Light Horse. Indigenous men were also among the tunnellers beneath Hill 60 during the Battle of Messines in June 1917, and were to the fore in the Light Horse charge in the Jordan Valley. Presently, around 115 Indigenous casualties are known, while others, such as Ben Murray from the Flinders Ranges, were taken prisoner.

Murray survived, returning to the South Australian outback and living beyond the age of 100 years.

Those who came home, however, faced an ungrateful nation that did not want to recognise their sacrifice. They were still thought of as ‘inferior beings’. All the racial restrictions remained in place. Indigenous ex-servicemen could not even enjoy a beer alongside their warfront comrades.

Their military pay was often withheld and they were offered no repatriation services for the terrors they had encountered. Even the best agricultural land on certain Indigenous missions was taken away and given to white returned soldiers to farm.

Some Indigenous men had earlier fought in the Boer War (1899–1902) in South Africa. It is believed that several from Queensland, used as ‘black trackers’ near Bloemfontein, found it difficult to return home to Australia, owing to the racial restrictions of the White Australia Policy.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 16.11

Social and ethnic division

Many commentators today claim that the war experience first time. They emphasise that it was not the colonial created a unified national feeling in Australia for the struggles that led to Australian Federation in 1901 that had developed this, but rather national pride in a large warfront ‘blood sacrifice’; that is, the scale of Australian military casualties.

When historians have studied the Australian home front during and immediately after the war years, however, they have not discovered an enhanced sense of national unity so much as evidence of social division and ethnic discord.

The two conscription struggles are dramatic examples of this. Australians had never felt so divided over a single issue. It split families and ended friendships as well as emphasising deep religious, political, class and ethnic divisions throughout society. The negative economic effects of war had also fallen heavily upon working people. They struggled with high unemployment and inflation, as well as falling wages. When war broke out, there were few strikes, but from the mid-war period (1916–17) onwards, industrial disputes mounted.

Furthermore, war involvement led to a sustained official attack on civil liberties and democratic rights. There were almost 3450 prosecutions under the War Precautions Act.

People were imprisoned for speaking out against the struggle. Censorship was more severe in Australia than in Britain, muzzling all forms of opposition. Nevertheless, anti-war activity remained a constant and increasing feature of the home front experience as a sense of loss, anxiety and sadness mounted.

War propaganda, as we have seen, contained a powerful strand of anti-Germanism. Germans composed a substantial minority population, especially in Queensland, New South Wales and South Australia. Before the war they were regarded as one of the most favoured ethnic groups. The war, however, transformed this, as hatred for all things German rapidly grew. Germans lost their jobs, their property and their votes. Their schools and newspapers were closed down. They were vilified in the street, in the press and in films such as The Hun and The Enemy within the Gates.

Anti-German riots occurred in several Australian cities and towns, including Melbourne, Perth, Lismore, Broken Hill and Charters Towers.

After the war, 6180 German people were deported from Australia to Europe, crammed into nine ships during 1919 and 1920. Other ethnic scares during the war involved the Irish, Southern Europeans, Turks, Jews, Afghans and Asians – and, from 1917, Russians. From 1915, Aliens Restriction Orders curbed ethnic freedoms in much the same way as the White Australia Policy restricted non-whites.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 16.12

- Assess how substantial social and ethnic divisions in Australia were during World War I.

- Identify the causes of such divisions.

- Describe the nature of anti-Germanism.

- Recount the effects this had on German individuals and their communities in Australia.

- Discuss the forms of ‘anti-foreigner’ feelings that existed.

- Explain the ways war involvement intensified antagonism.

- Recall how divided Australian society was by 1919.