16.2 Where Australians fought and the nature of warfare

Gallipoli: the landing and digging in

The first Australian casualties of the war (Able Seamen John Courtney and Bill Williams) were not killed on a Turkish beach, but rather in a jungle in German New Guinea, near Rabaul in early September 1914. The Gallipoli landings were still more than 7 months away.

The Gallipoli campaign was also not the first large military encounter in which Australian troops had fought. Thousands of Australian volunteers had joined British regiments in the Maori Wars (1845–47 and 1863–68); New South Wales infantry had supported Britain at the Sudan in 1885; and Australian blue jackets (sailors acting as soldiers) had helped suppress the Boxer Rebellion in China in 1900–01. Around 20 000 Australian servicemen and irregulars had also fought beside Britain in the Boer War (1899–1902) in South Africa. It was said in 1900 that: ‘from … the landing of Australian troops on African soil will date the true birth of Australian nationhood’.

It was to be the Dardanelles campaign (February 1915 to January 1916) and the Gallipoli landings of April 1915 that would eventually be viewed in this light. Around 16 000 ANZAC (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) troops were involved in the first Gallipoli assault at dawn on 25 April 1915. Throughout that day, more than 2000 would be killed and wounded. The ANZACs were part of a far larger Allied force of British and French, in what has been described as one of the most mismanaged military campaigns in history.

The 70 000 Allied troops included Irish Fusiliers, Indian Ghurkha and Senegalese battalions, a Maori Contingent and a Jewish Legion.

The idea behind the campaign – to open up a supply route to struggling Russia through the Bosphorus and Black Sea; and perhaps even knock Turkey out of the war – was over-ambitious and ill-judged. The British, underestimating the Turks’ capacity to defend their country, expected to succeed by a naval bombardment that began in February. By mid-March it had failed dismally and an amphibious invasion of ground troops was substituted.

Source 16.5 The military invasion of Turkey in April 1915 (03:45)

However, seaborne military assaults are difficult to mount tactically and, above all else, rely on surprise – an ingredient that was entirely lacking on 25 April. The Turks had been given 4 weeks to prepare.

The ANZACs, training in Egypt en route to the European front, were unfortunate enough to become caught up in this disastrous campaign.

Intelligence was faulty and maps unreliable.

Because of a navigation error, the ANZACs were landed at the wrong beach (later named ANZAC Cove), 2 kilometres too far north of the planned entry point.

Therefore, instead of finding a gentle slope behind the beach as expected, they were faced with cliff-like hills, around 100 metres high. In one respect, this initially helped the landing, as the Turks were not expecting any force to come ashore at this difficult location. They had fewer than 500 defenders there. Further, the steep slope offered some protection from enemy fire.

Some officers recommended total evacuation during that first afternoon, but there were insufficient boats available. From this time until the Allied retreat at the close of 1915, the Australians and New Zealanders were confined to defending a line approximately 1 kilometre inland, dug in, boxed up and raked by gunfire from the Turkish defenders on the surrounding hills above them.

Source 16.5a During May and August 1915, Ellis Ashmead Bartlett recorded footage of life at ANZAC Cove. This is a portion of that footage, restored by Weta Digital. (01:10 - no audio)

John Simpson Kirkpatrick, the best-known ANZAC at Gallipoli, was born in South Shields, England. He had once been a British ‘donkey boy’, taking children for rides on the beach at Whitney Bay, on the Tyneside in north-east England. He had illegally jumped ship in Queensland before joining up. The donkey, named Duffy, that he used at ANZAC Cove to carry wounded men was from Greece.

Gallipoli: failure and withdrawal

Most military historians conclude that Gallipoli was ‘a sideshow’ to the main events of the Western Front. They also see it as a tragic waste of human life that was poorly conceived by Lord Kitchener, the British War Secretary and Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty. By the time it concluded, for no territorial gain whatsoever, there had been more than 392 000 casualties.

Almost 131 000 troops from all the nations involved had died. Only the Turks could celebrate at having repulsed a major military invasion.

The role of the Australians and New Zealanders was secondary in strategic importance to the British onslaught at Helles, further to the south.

The French, who landed at Kereves Dere and Kum Kale, also sustained many more casualties.

Nevertheless, the ANZACs were widely praised for their skill and tenacity as assault troops. It was not expected that ‘mere colonials’ would perform so courageously under concentrated fire. There were some episodes of terrible carnage on both sides as the ANZACs beat back Turkish attacks or engaged in poorly planned assaults. On 8 May, around 1000 ANZACs were killed in an hour in a failed attack on Krithia. On 19 May, there were an astonishing 10 000 Turkish casualties in 1 day when they attacked the ANZAC trenches. In early August, during a diversionary battle for Lone Pine (or ‘Bloody Ridge’ in Turkish terms), the Australians took the post after fierce fighting, but lost 2200 men. At the same time, on one narrow strip of ground called The Nek, which was not much larger than a tennis court, hundreds of members of the 8th and 10th Australian Light Horse regiments were needlessly sacrificed.

This battle forms the central episode of Peter Weir’s 1981 film, Gallipoli, but the main officer responsible was actually Australian, not British.

This August offensive was finally abandoned after 12 000 British, Indian and ANZAC troops were lost.

On 7 December 1915, the British Cabinet ordered a retreat of all Allied troops from Gallipoli. A British war correspondent, Ellis Ashmead- Bartlett, and a young Australian journalist, Keith Murdoch, had at last exposed the terrible conditions and flawed military campaigning to the British leaders. Winter had set in with freezing blizzards in November and thousands were already being evacuated with frost bite, dysentery, typhoid, influenza and trench foot.

One of the greatest disasters in British military history ended for the ANZACs on 19 December 1915. The Australians departed, shattered to leave more than 8000 of their dead behind, but comforted to have stuck it out so resolutely and to have gamely played their part in such a hopeless cause.

Chemical warfare (tear gas) was introduced on the Western Front by the French in August 1914. Germans began using chlorine gas at Ypres in April 1915. The British soon followed. The latter had first experimented with poison gas against the Maori at Ohaeawai, New Zealand as early as June 1845.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 16.6

Western Front: Australians at the Somme

By November 1914, the European war had reached a stalemate. The trenches of the Western Front, with its ‘no-man’s-land’ of immense shell holes, tangles of barbed wire and the littered bodies of men and animals sandwiched between them, stretched like an ugly scar for nearly 800 kilometres, from the Belgian coast to the Swiss border.

The 1st and 2nd Australian Divisions arrived at the Western Front in mid-March 1916. The 3rd and 4th Divisions followed in April and May. They came to the 130 kilometres of the line held by the British, which extended from the River Somme in the South to Ypres in Belgium.

In 1914–15, the Western Front had already experienced savage battles and huge casualties, but the fighting in 1916–17 would dwarf these earlier struggles. The campaigns the Australians were now to face made Gallipoli seem a relatively modest affair. These new battles were usually fought over hundreds of metres of blasted, muddy ground with a loss of thousands of lives. This became known as ‘attrition warfare’.

In Australia’s first major engagement at Fromelles on 19 July 1916, the recently arrived 5th Division was sent into combat in bright daylight in a poorly devised exercise. Thousands of untried, exhausted men were mown down by German machine-gun fire and nothing significant was achieved. There were 5533 casualties across one evening, almost 2000 of whom were killed. The British commander, General Sir Richard Haking, who was responsible for the bloody fiasco, merely commented that the experience had done the men ‘a great deal of good’. It remains Australia’s worst single wartime loss.

As it had begun, so unfortunately it was to continue. During the extensive Somme offensive, Australian units fought at Pozières under devastating bombardment. When they were withdrawn in early September, the 1st, 2nd and 4th Divisions had lost another 23 000 men.

Throughout the freezing winter of 1916–17, they continued to fight. During April and May 1917, in the two rushed and bungled battles of Bullecourt, another 10 300 Australians became casualties.

British officers generally believed that Australians were ‘fine fighters’ but poor soldiers.

They were seen as badly disciplined and dressed, and lax at marching and saluting. The Australian rank and file would only salute officers – whether Australian or British – whom they respected. This meant they did not salute often. War experience was changing their formerly favourable attitude towards British culture and civilisation.

Western Front: the 1918 campaigns

Statistics show that the AIF did have disciplinary problems. In the first half of 1917, the Australian desertion rate was four times greater than the other British Dominion troops. By March 1918, the British had less than one soldier per thousand in prison for disciplinary offences. Canada, New Zealand and South Africa had around 1.5 per thousand, but Australia had 9 per thousand.

Many Australian recruits did not come from a military background and arrived at the warfront with less training and drilling. They tended to show more commitment to each other than to the military hierarchy.

They were quick to realise when they were being led by incompetent officers and reacted accordingly. Whereas the British Army code pronounced the death penalty for 17 different offences, the Australian Defence Act 1903 (Section 98) allowed capital punishment only for mutiny, desertion to the enemy or treason.

What the Australian forces required was inspired, methodical leadership that understood the new technology of battle. During 1918, they began to receive this from a number of outstanding commanders, particularly Major General John Monash and Brigadier General William Glasgow.

The war by this stage had reached a critical point. During 1917, Russia exploded into revolution and withdrew from the fighting. The French army had been checked by huge troop mutinies against the endless slaughter. Britain and Germany were both approaching exhaustion. In early 1918, Germany, using divisions brought westward from the former Russian front, mounted a huge offensive to smash through the Allied lines before US troops arrived in Europe in large numbers.

![Source 16.7 The band of the Australian 5th Brigade marches through Bapaume on 19 March 1917, while the town is still burning after the German withdrawal [AWM/E00426].](https://www.cambridge.edu.au/go/epub/library/Humanities9/OEBPS/images/Chapter16/9781107654693_1713.jpg)

In these desperate months, Australian soldiers, led by Monash and Glasgow as well as Brigadier Generals John Gellibrand and Charles Rosenthal, played a crucial role in avoiding defeat. At Villers-Bretonneux, on the third anniversary of the Gallipoli landing, the 59th and 60th Battalions retook the town after a wild bayonet charge and hand-to-hand fighting from house to house, which effectively halted the great German offensive. Above the blackboard in a school room at Villers-Bretonneux today are the words: N’oublions jamais l’Australie (‘Never forget Australia’).

Australians and Canadians then spearheaded the Allied counter-offensive of 8 August at Amiens, using infantry coordinated with tanks, artillery and aircraft. German General Erich Ludendorff later declared this ‘the black day of the German army in this war’ as 13 000 of his troops were taken prisoner. From this point until 5 October – when, in their final engagement, the 2nd Australian Division captured the French town of Montbrehain – the Australian Corps had advanced 60 kilometres into enemy territory and played an important role in both ending and winning the war.

Source 16.7a This footage of Australian soldiers was shot by Herbert Baldwin and George Wilkins in the final year of the war. (00:25 - no audio)

Conditions of trench warfare

The trenches of the Western Front were an elaborate system of excavations, honeycombed about 2 metres deep into the earth. Due to almost constant conditions of fog, rain, sleet or snow, the earth itself was usually converted into mud and slime, with the land in between churned up by high explosives into a landscape resembling the craters of the moon.

Each trench system contained an offensive front line defended by barbed wire, backed by a defensive or reserve line containing the soldiers’ dugouts where they rested and tried to sleep, plus a third supply or support trench, containing ammunition, food and other equipment. These were connected by communication trenches that criss-crossed the landscape. Sometimes the enemy trenches could be as close as 15 metres (as at Gallipoli) or they could be as distant as a kilometre: usually they were separated by around 90 to 275 metres of ‘no-man’s-land’.

Soldiers might spend 3 or 4 days in the front trench, then another 3 days at reserve or supply lines before being withdrawn for four or more rest days behind the lines. At Villers-Bretonneux in 1918, however, the Australian 35th Battalion spent a record 33 days in the front-line trenches. Incessant bombardment could drive men mad with ‘shell shock’, which their superiors, planning ambitious manoeuvres far away, tended to deny as a ‘real’ medical condition. Around 80 000 men in the British lines succumbed to shell shock during the war.

Trenches were usually open to the weather and men stood at times knee-deep in stinking mud and water. Sanitation was primitive or non-existent, and there were millions of rats (some as big as cats) that fed on the corpses of the fallen. Trench foot and trench mouth – extreme fungal infections that could turn to gangrene – were common, especially in the earlier period of the war, while painful trench fever was contracted from lice infestation. Dysentery, typhus, cholera and death from exposure to extreme cold (especially during the freezing winters of 1916 and 1917) were also common.

This was far removed from the heroic images that men had earlier been fed at school, in their adventure books or through the press.

Three days after the Australians captured Villers-Bretonneux, Gavrilo Princip, the young man whose shots at Sarajevo had started the war, died of tuberculosis in an Austrian prison hospital.

RESEARCH 16.1

War historian Les Carlyon paints a terrible picture of Australian troops at the Somme in late 1916. Soldiers tried to find shelter in freezing trenches, collapsing under the weight of muck and rainwater. There was little wood or kerosene for heating and open fires were disallowed. Wounded men lay in the open for up to 12 hours before rescue from the sucking mud. The only recompense was comradeship, humour and community (or, in Australian terms, ‘mateship’). These were practices shared by men of all nationalities, not simply Australians, as they struggled to survive the ‘monstrous boredom’ and ‘intense anxieties’ of trench life.

Desert campaigns

When the war began, many experts believed it would be won by gallant cavalry charges, as in earlier campaigns. But in the muddy stand-off of the Western Front there was little chance for this. However, across the Middle East (in Egypt, the Sinai Peninsula and Palestine, following the failure of Gallipoli) it would be a different story.

Here, brigades of the Australian Light Horse fought highly mobile, mounted campaigns and achieved some remarkable victories.

Around 85% of Light Horsemen were from the Australian bush where they had learned to ride and handle horses expertly. Their horses were known overseas as ‘Walers’ – sturdy, solid mounts of great endurance, speed and stamina.

Walers soon gained a reputation as the best cavalry horses in the world. Around 160 000 of them would serve in World War I.

The Australians fought against rebellious Arab tribes (such as the Senussi) that were supporting Turkey and also contested the Turks at Romani (near the Suez Canal) and Magdhaba, en route to Palestine, during 1916.

Source 16.7e This footage of the Australian Light Horse was taken during the Desert Campaign. (01:06 - no audio)

On 31 October 1917, two Light Horse regiments of the 4th Brigade under Lieutenant General Harry Chauvel mounted a successful cavalry charge, trotting then galloping across 3.7 miles of broken ground under heavy fire to take the important strategic centre of Beersheba. Following this – which was one of the last great cavalry charges in history – the Australians rode on to take Gaza, Semank and Damascus. They were the first Allied troops to enter Jerusalem in triumph. Their 400- mile advance was summarised by the British Commander, General Edmund Allenby as ‘the greatest cavalry feat the world has known’.

Source 16.7f The Light Horse in the desert. (03:56)

Far less acceptable, however, was the behaviour of many hundreds of Australians and New Zealanders who attacked the Bedouin village of Surafend, near Jaffa in December 1918 and conducted a massacre of between 20 and 137 male Arab civilians. Allenby condemned the assault as the work of cowards and murderers.

Another sad aftermath of the desert campaign was the official decision not to repatriate the valiant Waler horses to Australia or New Zealand along with their riders. They, too, became the casualties of war. Only one horse was returned. Later, some members of the Desert Mounted column raised a memorial to their dead or abandoned horses in Sydney. In part it read: ‘to the gallant horses who carried them over the Sinai Desert into Palestine 1915–19. They suffered wounds, thirst, hunger and weariness almost beyond endurance but they never failed. They did not come home.’

About 23 000 of the 61 000 Australian soldiers who died in World War I have no known graves.

Casualties

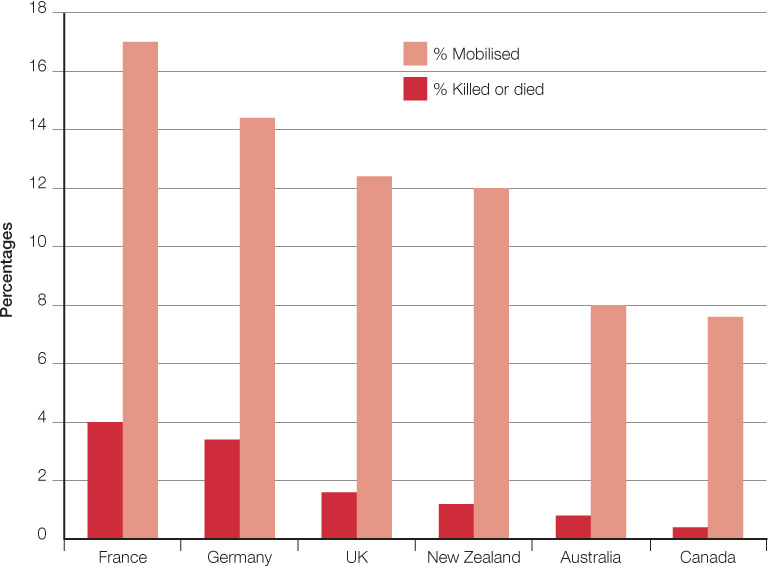

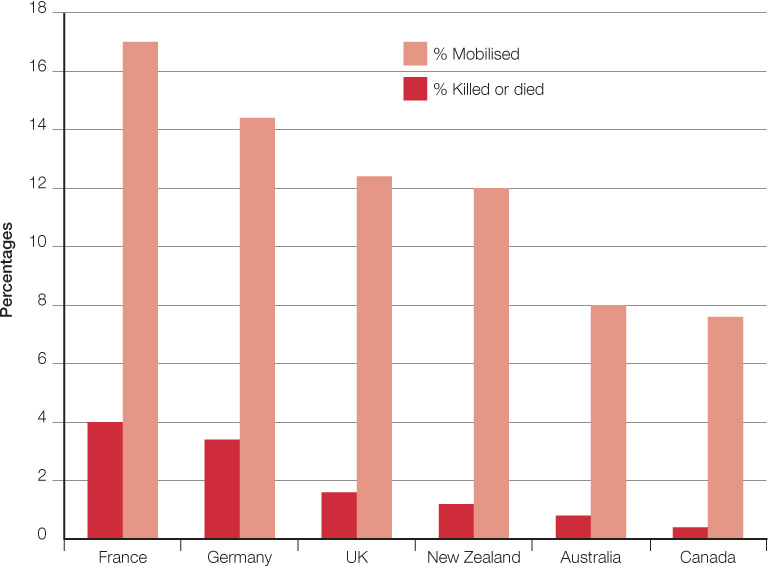

The numbers killed in World War I were more than double those of World War II. The exact casualty toll will never be known and the figures provided alter substantially in different accounts. However, in rough terms about 16.5 million people died and around 21 million were wounded; or roughly 37.5 million casualties, of which more than 40% were civilian.

Another way to look at it is in terms of deaths per day. The war lasted for around 1550 days, which means that on every one of these days, there were almost 23 870 casualties (10 645 of whom were killed). It is difficult to adequately grasp or visualise such appalling rates of death and destruction.

Australians read the mounting casualty lists in black-bordered columns in their daily newspapers.

They were also posted at railway stations, ferry terminals, post offices and factories. Families awaited the dreaded official telegram.