16.1 Causes of World War I

In terms of death and destruction, World War I was one of the greatest catastrophes in human history. Surprisingly, it was begun by the actions of a headstrong grammar school student. Gavrilo Princip was a sickly 19-year-old, just finishing high school, when he shot and killed Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria-Hungary, and his wife Sophie on the morning of Sunday 28 June 1914 in the Bosnian town of Sarajevo. Princip and his fellow conspirators were all young Serb nationalists who resented the recent absorption of Serbia into the Austro-Hungarian Empire. By their act of terror they hoped to free Southern Slavs (Serbs, Croats and Bosnians) from Austrian control.

Why did this single assassination lead to the immense calamity of World War I? It was because the various nations of Europe were locked in an intricate series of political alliances, diplomatic arrangements and military agreements that committed a nation to war if its ally was threatened, often without the full knowledge or consent of their populations. There was little international openness, extreme territorial competition for colonies and an escalation of armaments manufacture, along with much general distrust and suspicion. All these features contributed towards the fateful escalation into full-scale warfare over the following 5 weeks. The assassination of the Archduke, who was also heir to the Austrian throne, was therefore the catalyst for the war.

First, Austria, with Germany’s encouragement, declared war on Serbia (28 July 1914) in retaliation for the assassination.

This caused Russia to mobilise millions of troops in support of Serbia (29–30 July 1914). Russia and France were secretly allied. Germany therefore responded by declaring war on both Russia (1 August 1914) and France (3 August 1914). After the initial declarations of war, Germany’s plan was to first attack its principal rival, France; and, following a hopefully swift victory, to then turn its forces eastward upon Russia. This was known as the Schlieffen Plan.

Britain initially hoped to stand aside from a continental war, using the Royal Navy to blockade German ports, while providing only token assistance and financial aid to France and Russia.

After Germany, France and Russia had tired, Britain then planned to step in and impose peace terms upon all. Yet when Germany accelerated its invasion of France by passing through neutral Belgium on 4 August, Britain responded to this diplomatic violation by also committing itself to sending in ground troops.

Britain was bound by the Treaty of London (1840) to protect Belgium militarily.

The heads of state in three of the major fighting nations were closely related. Britain’s King George V and Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm II were the grandsons of Britain’s Queen Victoria. The wife of Russia’s Tsar, Alexandra, was also Queen Victoria’s granddaughter. Kaiser Wilhelm and Tsar Nicholas II, in turn, were the great-great grandsons of Tsar Paul I. From a certain perspective, therefore, World War I could be viewed as a massive family feud.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 16.1

Because Britain was now at war, Australia, as a self-governing Dominion within the British Empire, saw itself as automatically at war with Germany and Austria-Hungary as well. Australia’s interests were seen as identical with Britain’s. Its head of state was the British monarch, it possessed no diplomats of its own and its foreign policy was in the hands of the British government. One of Australia’s greatest tragedies had begun.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 16.2

War’s outbreak: European reactions

World War I was called ‘The Great War’ at the time. Of course, nobody knew that a second world war would one day erupt, so there was no point numbering this one as ‘the first’. Instead, participants soon began to claim that this ‘Great War’ would be ‘the war to end all wars’ and that it would ‘make the world safe for democracy’.

As we have seen, however, it was brought about more by the shifting balance of power in Europe.

Britain, for instance, fought not only to defend Belgian neutrality but also to prevent European domination by Germany and to protect its colonies in Asia, Africa and the Pacific.

Populations on both sides of the struggle were told that they were fighting for justice and freedom. The politicians, religious leaders and newspapers of each nation claimed that it was fighting in its own self-defence, although that usually meant invading the territory of some other nation. Therefore, as soon as war was declared, many people were overcome more by a spirit of militant nationalism than any desire for peace and universal friendship.

Each nation proclaimed that ‘Almighty God’ was on its side. Each side blamed the other for causing the war. In the capital cities of Berlin, Paris, London and Vienna, there were loud prowar demonstrations. Whitehall and Parliament Street in London were thronged with people chanting, ‘Down with Germany’ and singing ‘Rule Britannia!’ In Munich, a young, joyful Adolf Hitler – the man who 25 years later would provoke World War II – was captured on camera among the cheering masses outside the Feldherrnhalle (Marshall’s Hall) in Munich. From Paris and other French cities, 4300 trains, decorated with flowers and flags, carried tens of thousands of conscript troops rushing to meet another 11 000 German trains, similarly packed with soldiers. The troops called ‘To Paris!’ and ‘To Berlin!’, but their real destination would soon be a wasteland of mud and trenches. For most, the Great War began in an atmosphere of innocence and naiveté. Few understood what modern, technological warfare really meant. The last substantial European conflict – the Franco-Prussian War – had been long ago in 1870.

Britain had recently fought the Boer War (1899–1902) in South Africa, but that was a highly mobile struggle, often conducted from horseback.

The military generals themselves had little direct experience of warfare. They visualised rapid campaigns, won by aggressive cavalry charges and a war that would be ‘over by Christmas’. They did not understand that the new military technology – especially howitzers and machine guns (firing 500 rounds per minute) – favoured defenders over attackers.

In the first month of the war, France alone suffered 300 000 casualties. By war’s end, some 17 million soldiers and civilians had died.

Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, had visited New South Wales in May 1893 on a hunting expedition. In 10 days, he shot around 300 animals. During his life, he is estimated to have killed 300 000 animals.

War’s outbreak: Australia’s reactions

As the European nations stumbled into war, Australia was in the midst of a federal election campaign. On 31 July 1914, following news of Russia’s mobilisation, Labor leader Andrew Fisher declared that Australia would support Great Britain ‘to the last man and the last shilling’.

The Liberal Prime Minister, Joseph Cook, on the previous evening had spoken about the coming of ‘Armageddon’ and promised that ‘when the Empire is at war so is Australia at war’. Great Britain would not declare war for another 5 or 6 days. The news of Britain’s declaration was received in Australia at 12.30 p.m. on 5 August.

Such eagerness has encouraged some historians to see Australia as ‘terrifyingly willing to go to war’. Australians, positioned on the other side of the world, probably understood far less about Sarajevo and the fatal web of national alliances than the European populations themselves. They tended to think of warfare as short, heroic and glorious.

As in Europe, crowds gathered in the major cities to demonstrate their support. In Melbourne, for instance, after cheering for Britain, a mob attacked the German club, before turning upon unoffending Chinese in Little Bourke Street. War support could quickly descend into overreaction and hysteria; and local Germans soon became targeted as ‘Huns’ and ‘cultural monsters’.

If we shift the focus away from the flag-waving crowds and look across the entire nation, what do we see? While some people expressed enthusiasm, others reacted with resignation, worry and alarm. Some small groups, such as Quakers and socialists, expressed outright opposition. Mothers, sisters and wives were deeply concerned for the safety of sons, brothers and husbands who offered themselves as military volunteers. Yet freedom to speak out against the war was rapidly curbed by the War Precautions Act 1914.

Economically, war’s outbreak brought a sharp downturn, as global markets were disrupted and trade routes threatened. The outcome was stagflation, as prices and unemployment both rose sharply. Wages were frozen and strike activity curbed. In Queensland, unemployment numbers quadrupled between August and December 1914. In New South Wales, the prices of imported goods jumped 20%. For Australian workers generally, and for farmers already struggling with a severe drought, these sharp economic blows brought great hardship.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 16.3

The first military shots of World War I were fired in Australia. At around 10.45 a.m. on 5 August (1 hour and 45 minutes after Britain and Australia’s involvement in the war began), the gunners at the Fort Nepean Battery, Port Phillip Heads, in Victoria opened fire on the German cargo ship, SS Phalz, which had just steamed out of Port Melbourne. The Phalz was commandeered and used by Australia as the troopship HMT Booroora during the war.

Enlisting to fight

In August 1914, Australia had a permanent army and citizen’s militia force that together numbered 45 645 men. In January 1911, Australia had been the first English-speaking country to introduce compulsory military training of young males aged 12 to 17 years. There had been resistance to this scheme. Around 28 000 youths had been prosecuted and 5732 imprisoned for failing to comply. Yet 100 000 cadets were undergoing military drills by 1914. Australia also possessed a small navy, a new officer training centre at Duntroon and the beginnings of an air force.

All this, however, had been introduced to defend Australia directly. It was widely believed that the coming war would be fought in the Pacific against Japan, rather than in Europe and the Middle East against Germany, Austria and Turkey.

Japan at the time, however, was no real military threat to Australia. When the war began, Australia immediately placed its navy under British control.

It also needed to recruit volunteers quickly for overseas military service. On 3 August, 2 days before Britain declared war, the Australian Cabinet offered to send an initial force of 20 000 men.

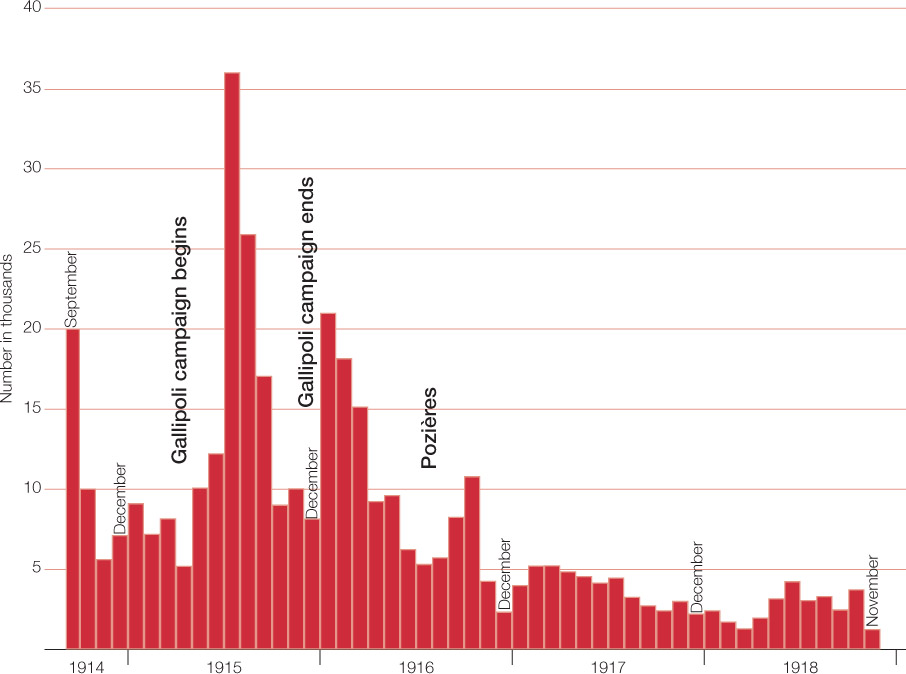

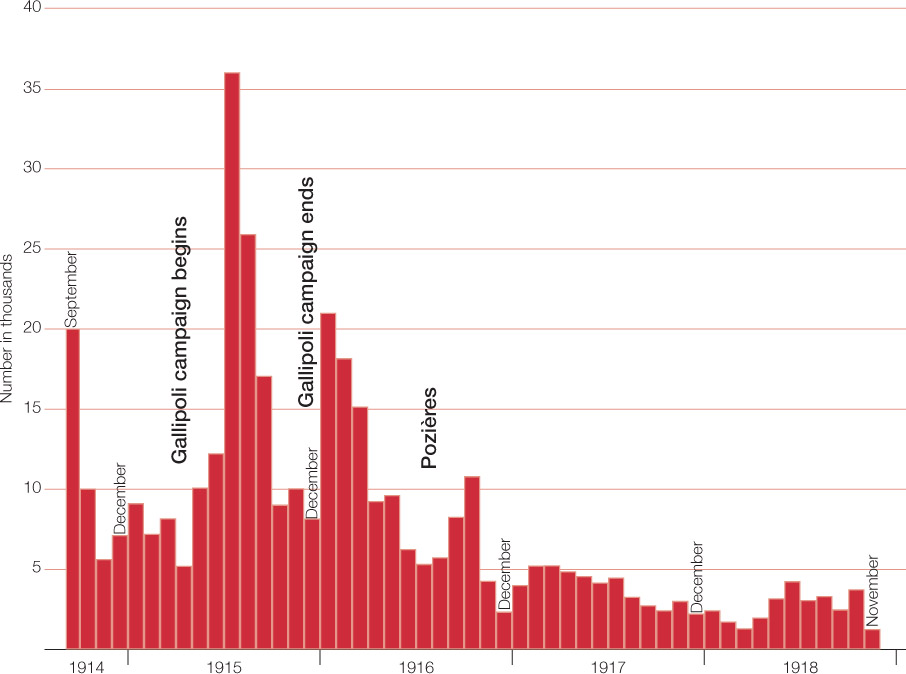

Little did they know that over the next 4 years, 416 809 would enlist, 331 781 of whom would serve overseas. Even this was a relatively small force in comparison with the millions of British, French, Russians and Germans who fought. Yet it was an enormous sacrifice for a small nation of less than 5 million people: it represented 38.7% of all eligible males in Australia aged 18–44 and, unlike in other combatant nations, it was raised by voluntary enlistment only.

Some historians write of ‘a rush’ by eager young recruits to enlistment centres. Others show that the number initially accepted was modest. On 8 August, the Sydney Morning Herald reported that only 735 men had turned up at Sydney’s Victoria Barracks. In the first month, only 700 of the 2000 who had offered themselves were considered medically fit. Later in the war, Minister for Defence George Pearce found, to his surprise, that enlistment statistics had been artificially inflated by 21 000 because ‘perhaps 20 or even 50 out of every hundred [recruits] had frequently, during the early stages of the war, failed to turn up’ for embarkation on the troopships! Nevertheless, by the beginning of 1915, official statistics showed that 52 561 people had been accepted into the Australian Imperial Force (AIF).

Physical and medical standards were initially demanding and many were turned away. Within 5 months, Australia had more than doubled its first promise of 20 000 men. Enlistment continued to rise in 1915 but then began to falter. In 1917, the annual total had fallen by two-thirds, and in 1918 by five-sixths of the 1915 figure. Australia, seemingly, had exhausted itself in its determination to support Britain in combat.

![Source 16.3 The original 12th Brigade marches through Hobart to depart for the war on 20 October 1914 [AWM/H11609].](https://www.cambridge.edu.au/go/epub/library/Humanities9/OEBPS/images/Chapter16/9781107654693_1707.jpg)

Although Australian troops were often called ‘bushmen’, only 17% were from the countryside and 83% from urban areas. Around 34% were tradesmen (skilled workers) and another 30% were labourers (unskilled workers).

Reasons for enlisting: the importance of Empire

Why did so many men, a large proportion of whom were not much older than yourselves, decide to enlist?

When historians try to understand the soldiers’ motives, they meet both a frustrating silence and a confusing jumble of rationalisations, emotions and impulses.

It can safely be argued, however, that most Australian men had been prepared to fight for Britain by the nature of their schooling. In Australia, their ‘British patriotism’ was stirred by a continual ‘recounting of the heroic deeds of our forefathers’.

British heroism at such battles as Trafalgar, Waterloo, the Crimea, the Indian ‘Mutiny’, and the Afghan, Zulu and Boer wars was emphasised by teachers; and male children especially were encouraged to sacrifice themselves, when the time came, to the imperial cause.

Compulsory military training for all boys aged 12 years and over imposed the discipline of obedience and emphasised that warfare was the manly way to solve international disputes. Fighting for ‘King and Country’ in ‘the service of Empire’ was encouraged, for the Empire was presented as being ‘glorious’ in its vast dimensions and always virtuous. Such sentiments were often reinforced by the church and the family.

One soldier from Wollongong recalled that, due to such urgings, more than half of his class of 45 pupils went away to war. Eleven were killed and many others wounded. He concluded that they had all enlisted out of loyalty and duty. At least 90% had been ‘conscripted by their consciences’. But there were other reasons for fighting as well.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 16.4

- Describe what images first come to your mind when you think about World War I.

- Evaluate how predictable this war was.

- Assess how aware Australian military recruits were about what lay ahead for them in the fighting.

- Clarify why Australia’s existing army was for local defence only.

- Recall whether or not there was an initial rush of recruits.

- Explain why recruiting declined so dramatically between 1916 and 1918.

Other reasons for enlisting

The ‘call of Empire’ was strong in the Australian soldier. Yet historian Bill Gammage believes that most of the early volunteers were roused by a sense of adventure. Enlisting was seen as an escape from the monotony of everyday life and the tedium of the workplace. It provided a chance to travel and see the world outside Australia.

Many men also saw war as a glorious opportunity to ‘prove their manhood’.

After active recruiting began on 11 August 1914, a campaign of ‘hatred of the enemy’ was also mounted. This encouraged some recruits to express their motives in terms of anti-German hostility. ‘I am itching to get a dig at a few Germans,’ wrote a Melbourne volunteer; while a South Australian declared his intention to ‘get to grips with those inhuman brutes … [and] help wipe out such an infamous nation’. Some were simply carried along in a tide of peer-group pressure: their mates were enlisting so they would too. Others were shamed into going by female scorn at their lack of manliness. Some women sent men white feathers as a symbol of cowardice and this was reinforced by press campaigns attacking those unwilling to fight as ‘slackers’, ‘shirkers’ and ‘cold-footers’. Some left on troop ships to escape difficult situations on the home front: a failing marriage perhaps, an unhappy home or a gambling debt.

Yet it should not be forgotten that others were forced to ‘join up’ due to poverty. As we have seen, when war began, unemployment skyrocketed, wages froze and prices rapidly increased. The Australian countryside was also suffering severe drought. There were no state welfare services for the unemployed, only private charity. Cash-strapped men were attracted to the AIF’s offer of 6 shillings (roughly 60 cents) per day. In such times of hardship, economic motives could be as important as idealistic ones.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 16.5

- Discuss how ‘the British connection’ influenced Australian soldiers’ decisions to enlist.

- Clarify why soldiers often said they were ‘fighting for England’ rather than ‘fighting for Australia’.

- Evaluate how influential schooling was in encouraging soldiers to volunteer.

- Construct a list of all the motives for enlisting in World War I. Can you think of any other motives besides those covered in the text? How would you rate these motives in order of importance?

- Locate an Australian recruiting poster from World War I through an internet search engine, the Australian War Memorial website or a book such as Sam Keen’s Faces of the enemy (Harper and Row, 1986). Develop a class debate to analyse the poster’s message.

- What values does it represent?

- What sort of impact do you think this poster would have made at the time?

- Does it reflect an accurate image of the warfront? If not, why not?