15.4 Indonesia

State of the region during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries

The idea of Indonesia as a nation did not exist when the Dutch first came to the Indonesian islands in search of spices in 1595. At that time there were a number of different sultanates and kingdoms across the various islands, ruling people of different beliefs and ethnicities. However, by 1750 the Dutch East India had established treaty ports all over the archipelago, and had occupied significant amounts of territory.

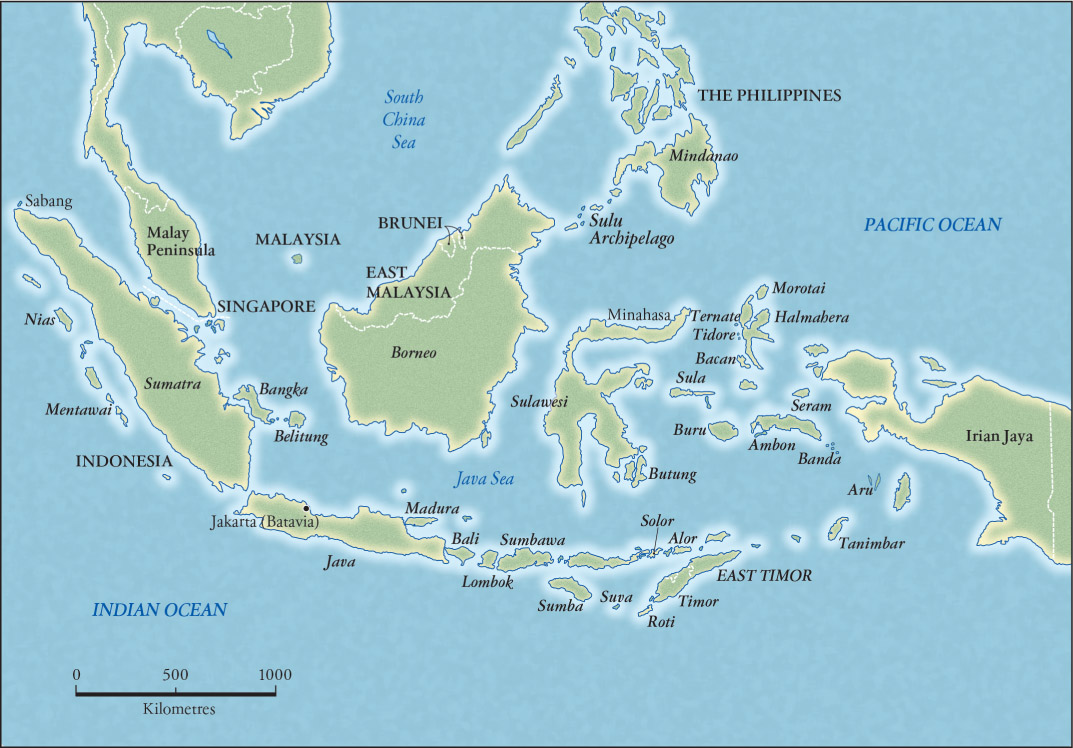

The present-day nation of Indonesia is made up of more than 17 000 islands stretching from the Indian Ocean towards the Pacific Ocean. Many of these are extremely small, but the largest are Java, Madura, Sumatra, Sulawesi, Borneo (which also includes the state of East Malaysia and the nation of Brunei), the Moluccas, Bali, Lombok, Sumbawa, Sumba, Flores, Timor (which includes the nation of East Timor) and New Guinea (which includes the nation of Papua New Guinea).

These islands over time have been subject to many cultural influences. Over the centuries, traders and seafarers from India, China, the Arab Peninsula and Europe (especially the Portuguese and Dutch) have had a great influence on these islands. Some of these traders stayed only briefly, while others had a lasting impact upon peoples and their cultures.

Puppet performances, known as wayang, reflect the cultural history of the Indonesian archipelago. Over the centuries people would gather at night in their villages to enjoy the mastery of the dalang (puppet master and narrator), who would make the flat leather puppets come alive and entrance them into the early hours of the morning. The village would resound with the voice of the dalang and the laughter of the audience.

Old Indonesian ways of storytelling were influenced by the arrival of Hindus from India from the first century CE and of their great epic tales, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. When Islam came to the islands in the fifteenth century, the puppet shows were seen as blasphemous because they involved the representation of human figures, which is largely forbidden in Islam. An ingenious way around this was to display only the shadow of the image on a large white sheet and thus wayang kulit was born (Source 15.10).

This video of a modern wayang kulit performance shows both the shadows and the puppeteer behind the sheet – https://www.cambridge.edu.au/redirect/?id=221.

Late in the sixteenth century, the Netherlands, a maritime nation, was eager to take over the spice trade in these islands from Portugal, which was a declining power. In 1595, Dutch ships managed to get to Java and thus began a series of Dutch ships coming to buy spices (in 1598, for example, 22 ships set out). These were mostly highly profitable voyages. One expedition made a profit of 300% on its outlay.

As well as pepper and other spices, the port of Aceh in Sumatra exported elephants to India for the sultans, rajahs and maharajahs to use in their battles and ceremonies.

Dutch East India Company

In 1602, the Dutch East India Company was set up to control the spice trade, and eliminate wasteful competition between Dutch traders. The Dutch government allowed the company to wage war, colonise and do anything else necessary to maintain a monopoly on the eastern trade. The company organised information about the sailing route to the East, built ships and warehouses, equipped and dispatched expeditions, invested funds and fought wars to maximise its profits.

In 1750, the Dutch East India Company made a huge profit on selling spices in Europe; approximately 17 times what it paid for them.

The Europeans were eager to buy spices that made their food much tastier, but the people of the Indonesian archipelago did not want any of the goods that Europe could supply.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 15.8

Trade between Asian ports

At the beginning of its operations, the only things that the Dutch East India Company were able to exchange for the spices it bought was silver and gold. Because silver and gold were in quite limited supply in Europe, this heavily restricted the growth of the spice trade. For this reason, the directors of the company decided to carry on a large intra-Asian trade, which means that they traded goods between various places in the Asian region. The company also sold other products from places in Asia to European markets. The company set up trading posts in coastal regions and bought spices produced in the local region.

At first the company only took over land near their ports. In 1619, it set up Batavia, on the site of the town of Jayerkarta (now Jakarta, capital of Indonesia). Dutch East India Company forts and trading factories were set up at important strategic places, such as Aceh (now in Indonesia), Malacca (Malaysia), Galle (Sri Lanka), Nagasaki (Japan), Canton (now Guangzhou in China), Cape of Good Hope (South Africa) and Bengal (India).

An amazing variety of products was shipped between these ports, including some items that are hardly known today. As we saw in the earlier discussion of Japan, the Dutch had a base at Nagasaki during the period when Japan was closed to outsiders. Each year the company sent eight ships to Dejima in Japan loaded with products such as cloth, ivory, sandalwood, ebony, fur clothing, pepper, sugar, amber, large dogs and other goods. Often ships were lost in typhoons, but this was still a profitable trade. They brought a wide range of Japanese goods back to Batavia, including silver, gold, copper, camphor, rhubarb, pearls, rice, curved swords and fur pelts.

Silver, gold, elephants and rhubarb

The Dutch East India Company took silver, gold and cloth from China, the Coromandel Coast (south-east India) and Surat (west India) to Galle, and returned with cinnamon, ginger, pepper, elephants, rhubarb and precious stones. At Peraka and Kedah on the Malay Peninsula, the company bought tin and sold Coromandel cloth and reals of eight. They also exchanged cloth goods for horses, wax, honey and slaves at Butung, an island near Sulawesi.

RESEARCH 15.2

The first multinational corporation

The Dutch East India Company was the world’s largest commercial enterprise and we can think of it as the first multinational corporation. From the eighteenth century, it had its own currency marked with its distinctive symbol or logo (see Source 15.14).

Change and continuity

The story of the Indonesian archipelago is filled with rivalries and conflicts between various local rulers and sultans, as well as between European powers. As the Dutch East India Company became established in this region, it became involved in struggles with and between various rulers in Java, Sumatra and the Moluccas. On Java, the great Sultanate of Mataram was in decline in the eighteenth century and the company became involved in a number of wars about who would succeed to the position of Sultan, and thus extended its control over the rich lands of Java.

The rulers of Mataram asked the company to help them in their struggles and the company was able to exploit rivalries between members of ruling families and advance its control over the wealth of the islands. The local sultans were not as concerned about the growing power and influence of the company as they were with the local struggles, and saw that the company could be a useful ally. As a result of these intrigues, the Treaty of Giyanti in 1755 divided the Kingdom of Mataram between the sultanates of Yogyakarta and Surakarta.

Decline of the Dutch East India Company

Through the seventeenth and into the eighteenth century, the Dutch East India Company paid huge dividends to its Dutch shareholders. However, the costs of administering the large areas around the forts and trading stations grew. The company fought expensive wars to protect their trading interests, becoming involved in rivalries and disputes between local princes and sultans, and there was also a growing level of corruption among its employees. At the same time, the company’s monopoly over trade in the East was being challenged by other European powers.

The Dutch had pushed the Portuguese out of the rich spice trade, but now the British were eager to extend their trading networks into the region.

The Dutch and the English fought a number of wars over access to these regions. By 1780, the British began to get the upper hand. When the Dutch supported the Americans in their rebellion against the British, the Anglo-Dutch war of 1780–84 ensued. The defeat of the Dutch also brought on the collapse of the Dutch East India Company.

The company lost 70% of its assets and many ships and trading stations to the British. In 1799, the great Dutch East India Company went bankrupt and its activities in the East Indies were taken over by the Dutch government.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 15.9

The Dutch East Indies after the company

In 1800, fewer than 6 million people lived in the Dutch East Indies. Some areas, such as the western coast of Sumatra, were scarcely populated. At this time, the Europeans had had little impact on the economic lives of most people. Europeans, particularly the Dutch, controlled small parts of east Indonesia, Java, Sumatra and the Moluccas.

These traders were located on coastal areas, together with Chinese and Arab traders who for generations had crossed the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean. However, trade was not an important activity for most people, who were engaged in agriculture and did not use money; they bartered crops and goods to meet their needs.

The most populated areas were in central and east Java, where high rainfall and rich volcanic soils allowed for intensive irrigated rice production.

The land here had been carefully terraced over generations and people were settled in towns and villages.

In other parts of the islands, conditions were poorer and people carried out slash and burn agriculture. The peasants cleared patches in the jungle, which they farmed before moving on to a different section. Most people were Muslims, but on some of the far eastern islands there were some animists. The Chinese performed ancestor worship and there were many Buddhists and Confucianists.

European struggles had an ongoing impact upon Dutch power in the east. The Netherlands were invaded by Napoleon’s forces and annexed by the French in 1806. As Britain and other forces carried on the struggle against Napoleon, the Dutch empire became part of the spoils. In May 1811, the British captured Batavia, appointing Sir Stamford Raffles as Governor-General of the Indies. Raffles was very keen for the British to expand its empire into the Indonesian islands. However, this was not to be and with the peace in 1816, the Netherlands regained their control over the Dutch East Indies. In order to pay for the costs of war, both British and Dutch rulers imposed forced labour on the Javanese peasantry along with heavy financial burdens.

Sir Stamford Raffles (1781–1826) was fascinated by the vegetation, wildlife and cultural monuments of Java, such as the ancient Buddhist monument at Borobudur. He kept a number of animals from Indonesia as pets. He reared a sun bear cub that joined the family for dinner, eating mangoes and drinking champagne.

Key incident: Treaty of London

The Dutch and the English had been competing in the east for some centuries when, during the Napoleonic Wars, the British took over Java and the Dutch territories in the Dutch East Indies. With the defeat of Napoleon, the Dutch were keen to regain their former territories, and were annoyed that the British had set up a new trading station at Singapore. They claimed that Raffles’ agreement with the Sultan of Johore to set up Singapore was not valid.

In 1820, Dutch and British negotiators began meeting to discuss these issues and to work out a way to return the Dutch territories. Talks dragged on until agreement was reached in 1824 with the signing of the Treaty of London. Under the terms of the treaty, Britain and the Netherlands agreed to exchange territories so that the Dutch held the Dutch East Indies and the British held Singapore and India. The Malay world was divided at the Straits of Malacca with the British holding sway to the north of the Straits and the Dutch to the south and west of the Straits. Under this arrangement, the Dutch gave up their colonies in India and Malacca, and the British gave up their trading post at Bengkulu (Bencoolen) and all their interests in Sumatra. The Dutch agreed that Britain could hold Singapore.

Thus, at the stroke of a pen in Europe, the lives of millions of people in Southeast Asia were changed. The Malays in Indonesia were subject to Dutch rule and the Dutch legal system, while the people of Singapore and, later, the Malay Peninsula were ruled by the British and subject to British law. In Indonesia, the language of the rulers was Dutch and across the Strait of Malacca it was English. These two parts of the Malay world evolved in different ways. Today the Strait of Malacca still forms the boundary between Indonesia on one side and Singapore and Malaysia on the other.

Source 15.16a The Treaty of London (02:05)

The early nineteenth century

The Dutch were introducing new ways into Java, and they consolidated their power over the Indonesian archipelago throughout the nineteenth century. The heavy burden on the peasantry caused widespread discontent, as did Dutch interference with the succession to Sultanate of Yogyakarta, especially among those members of noble and aristocratic families who lost out in these struggles. Conversely, members of other ruling and aristocratic families benefited from their association with the Dutch, and these divisions allowed the colonisers to flourish.

Often the Dutch ruled indirectly through a sultan or ruler, who appeared to have power and authority; however, a Dutch-appointed advisor (usually called a Resident) kept a close watch over the ruler and controlled his decisions.

Prince Diponegoro and the Java War of 1825–30

The Java War of 1825–30 was the last uprising led by members of the old elite. The central figure was Prince Diponegoro, who was the oldest son of the Sultan of Yogyakarta. Born in 1785, he was raised in a devout Islamic environment. When his father died in 1814, he expected to become sultan, but the Dutch appointed his younger half-brother, Hamengkubuwono, as ruler. In 1821, Hamengkubuwono died in a cholera epidemic that swept the land. Once more Diponegoro was passed over as Hamengkubuwono’s baby son was made sultan; Diponegoro was not even appointed regent for the young sultan. Diponegoro also believed the Dutch and Christians were turning the court away from a proper observance of Islam.

This was a difficult time in Java: a poor harvest and heavy taxes were causing great distress for the growing population. Diponegoro was disturbed by the Dutch plans to build a road through his rice fields, close to his father’s tomb. For Diponegoro, the death of the sultan, the famine and plague, and the eruption of Mount Merapi were very significant; he viewed them as signs that the infant sultan had lost the right to rule. Diponegoro believed that he was the ‘Just Prince’ who had to free the people from the oppression of the Dutch and their allies in the court at Yogyakarta in order to restore peace.

Supported by many among the Javanese elite and the peasantry, Diponegoro launched a holy war against the Dutch and the corrupt court.

There was great loss of life: 200 000 Javanese died, mostly of starvation, as well as 8000 Dutch soldiers. The gracious city of Yogyakarta lost half its people. Eventually, the war reached a stalemate. The Dutch were finding the war very expensive, so in 1830 they invited Diponegoro to a meeting, ostensibly to discuss a truce. However, they doublecrossed him and sent him into exile in faroff Sulawesi.

This war marked the end of any resistance to Dutch rule in Java. Historians have noted that at this time the Javanese were reacting to the challenge of the more modern Dutch society by harking back to traditional ways rather than moving forward, as they were to do in the twentieth century. Today, the Javanese regard Prince Diponegoro as a nationalist hero, and there are many streets and a university named after him.

Cultivation system

The Dutch had fought two costly wars in Java and Sumatra, plus another in Europe in 1831–32 when they unsuccessfully tried to stop the Belgians separating from the Netherlands to form a separate kingdom. This meant that the Dutch desperately needed more revenue. With all these wars, the Dutch had incurred debts of 37.5 million guilders (the Dutch currency of the day). In order to raise money, the Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies, Johannes van den Bosch, introduced the cultivation system in 1830. This system required every village to set aside one-fifth of its land for cash crops to be sold in Europe. Instead of growing rice, they had to grow sugar, coffee, tobacco, indigo, cinnamon or cochineal. If they did not produce these crops for the government, they had to pay a 40% tax.

The cultivation system was like a heavy system of taxation. It was confined to Java and the Minangkabau highlands in Sumatra. It did not affect the outer islands.

As well as bring an effective way of using the land and the labour of the Javanese, this was also a highly profitable system for the Dutch. Wealth flowed from the colonies to the Netherlands. From 1830 to 1840, the profit from Java was on average 9.2 million guilders per year. The 1840s was even more profitable, averaging 14.1 million guilders per year. In the 1860s, about one-third of Dutch government revenues came from the Indies. In all, from 1831 to 1877, 832 million guilders were sent to the Netherlands. This allowed the Dutch to quickly pay off their debts and to build railways, canals and forts at home.

However, this system was very bad for the Javanese. The forced delivery of crops for the government monopoly over 40 years had a long-term impact on the economy. It meant that any profits went out of the country and the Javanese could not invest in industry and new technologies to support their growing population (Java grew from about 7 million in 1830 to 16 million in 1870) or to raise their standard of living. The Dutch built a network of roads and railways across Java not only to transport goods but also to control the local population. There was little spending on hospitals, health-care or schools for Indonesians.

Although this was a very profitable system, criticism of it grew in the Netherlands. After the 1848 revolution, the Dutch people had more say in their government policies. Stories about the harsh cultivation system and its impact on the Javanese peasants were heard in the Netherlands. Dutch voters became concerned about what was happening with the cultivation system.

Max Havelaar

In 1860, the novel Max Havelaar was published and caused a great outcry in the Netherlands against the cultivation system. It appeared under a pseudonym, Multatuli, but was written by a former official in the Dutch East Indies, Eduard Douwes Dekker. It was a devastating description of the state of affairs in the Dutch East Indies, showing the corruption of the Dutch officials and the cruelty of the cultivation system, and depicting colonial rule as immoral and inhuman. The book was a plea for the Dutch king to improve the lot of his subjects in the Indies.

Middle-class opinion in the Netherlands wanted change, and because they were voters, they had some influence. After the publication of this book, the forced deliveries of various crops were phased out. Deliveries of pepper ended in 1862; cloves and nutmeg in 1864; indigo, tea and cinnamon in 1865; and tobacco in 1866. Coffee and sugar deliveries had been the most lucrative for the government and lasted longer. Sugar deliveries were ended during the years between 1878 and 1890 and coffee only in 1917.

The great Indonesian novelist, Pramoedya Ananta Toer, has argued that Max Havelaar did more than just end the cultivation system. He saw it as leading to the liberal policy that involved the setting up of schools in the Dutch East Indies. The Indonesian students who received an education at these schools went on to become the nationalists who founded the independence movement that finally expelled the Dutch in the 1940s. Pramoedya also notes that this novel was translated and read around the world, providing inspiration to the foes of colonialism everywhere. For many, this was the book that ‘killed colonialism’.

Position of Indonesia leading up to 1900

After the publication of Max Havelaar and the growth of the Dutch middle classes, a liberal policy was introduced in the Indonesian archipelago from the 1870s. It was introduced not only for humanitarian reasons but also to let private Dutch entrepreneurs come and make money in the Dutch East Indies. This policy saw the growth of large estates producing coffee, sugar, tea and tobacco, and also the exploitation of rubber and oil – resources found in Borneo and Sumatra and important to new industries in Europe.

As we have seen, the forced delivery of cash crops was slowly phased out across the Indonesian archipelago. The new system ended the great monopoly of the Dutch government in agriculture. With the passing of the Agrarian Law in 1870, private entrepreneurs could set up farms and other enter-prises. The Dutch could not own land, but could lease it from the government for up to 75 years or from local people for up to 20 years. During the period from 1870 to 1900, more Dutch men, women and children came to live in the Dutch East Indies. In Java, the number of European civilians increased from 17 285 in 1852 to 62 447 in 1900, a threefold increase over a period of 50 years.

The opening of the Suez Canal to shipping in 1869 made it easier to travel between the Netherlands and the Dutch East Indies, while improvements in steam navigation made the journey much more comfortable. Still more Dutch families settled in Java and other islands, employing Indonesian workers on their plantations.

Alongside these plantations, the Indonesian people grew rice and other crops for their own survival. During this era, agriculture in Java and the outer islands was intensified. The volume and the value of exports increased greatly, especially from the private entrepreneurs. In 1885, the value of exports was twice that of 1860. Much of this increase came from the private sector: in 1869, private and government exports were about equal but, by 1885, private exports were 10 times higher than those of the government. Chinese entrepreneurs also prospered, but the income of Indonesian entrepreneurs and that of artisans and waged employees fell. There was famine in Banten, west Java, in 1881–82 and in Central Java in 1900–02. Despite the wealth being created, the standard of living of ordinary people fell.

The cash crops were hit by diseases such as coffee leaf curl disease, which from the 1870s led to a fall in production. The sugar blight spread across Java from 1882 to 1892 and, with the development of beet sugar in Europe, sugar prices fell dramatically. The peasants working in sugar industries became unemployed.

Rice consumption fell, especially after 1885, and people had to eat cheaper introduced crops such as maize and cassava. The rural depression was worst in 1887–88. Later in the century, new strains of sugar were created and sugar production recovered.

During this period, the people were burdened by taxes. In 1904, a report showed the average household in Java owed 20% of its income to the government. Many turned to money lenders in order to survive; indeed, much of the tax bill of the colony was passed to ordinary people.

Private European companies that benefited from the roads, railways, harbours and irrigation works that the government built did not pay their fair share of tax. Ordinary people also paid for the cost of the Dutch expansion of control over the outer islands. For the Indonesian people, this was a system of shared poverty.

Education

Pramoedya Ananta Toer wrote that developments in education during this era killed colonialism.

In 1863, primary schools for European children were opened to local children, but high fees kept out most Indonesians. In 1867, an education department was finally established in the Dutch East Indies.

Many of the Dutch were opposed to extending education to Indonesian children. Some believed that education would make the Indonesian people harder to control and less accepting of Dutch authority over them. An opinion piece written in a newspaper of the time stated: ‘They will be less obedient because they are more acquainted with the norms and the way of life of the white man.’ Between 1871 and 1898, the number of primary schools increased from 263 to 516. Given the population numbers, this meant that most children still had no access to schooling. From 1871 to 1898, the numbers of male students increased fourfold, from 12 186 to 48 156, while the numbers of females grew from a tiny 4420 to just 8238. From the early 1870s, poorly resourced 3-year primary schools for the indigenous population were set up. Most of the funding was spent on Dutch children rather than on Indonesian children (see Activity 15.11).

There were very few high schools or higher education institutions for Indonesian students.

From 1873 to 1899 there were only 907 graduates of teacher colleges. The Dokter-Djawa School was set up to train Indonesian people to work as vaccinators. By the 1870s this had become a medical school for Indonesian male students, but only a small number of graduates flowed from this school. Between 1875 and 1904 there were just 152 graduates.

Indonesian doctors and teachers were paid a lot less than Dutch doctors and teachers. Often they were socially snubbed by Dutch officials and people in the Dutch East Indies, who strongly believed that they were superior to the Indonesians.

An 1863 government decree meant that all positions in the civil service were open to all in the colony, whatever their religion or ethnicity. But in practice, Indonesians in the civil service were often treated very badly. Even when they gained educational qualifications for higher positions in the public service, they found that these positions were often granted to Dutch people.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 15.10

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 15.11

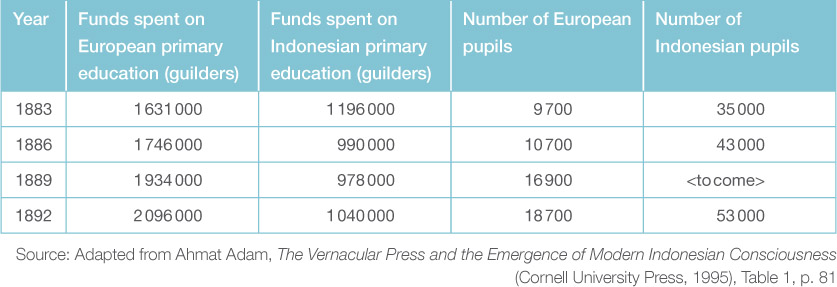

The following table lists the funds spent on European and Indonesian students in the period 1883–92.

Source 15.19 Funds spent on European and Indonesian students in the period 1883–92

| Year | Funds spent on European primary education (guilders) | Funds spent on Indonesian primary education (guilders) | Number of European pupils | Number of Indonesian pupils |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1883 | 1 631 000 | 1 196 000 | 9 700 | 35 000 |

| 1886 | 1746 000 | 990 000 | 10 700 | 43 000 |

| 1889 | 1934 000 | 978 000 | 16 900 | <tocome> |

| 1892 | 2096 000 | 1040 000 | 18 700 | 53 000 |

Source: Adapted from Ahmat Adam, The Vernacular Press and the Emergence of Modern Indonesian Consciousness

(Cornell University Press, 1995), Table 1, p. 81

Calculate how many guilders were spent on the education of European children versus that of Indonesian children for the years listed in this chart. What conclusions can you draw from these figures?

Newspapers

Gradually, educated Indonesian people, teachers, doctors and the junior officials began to discuss their situation and the difficult position of their own people. They were critical of both Dutch officials and senior Indonesian officials who came from noble families. Educated Indonesians set up newspapers and journals, and saw the value of modern education and modern science for the progress of Indonesia. They started to feel they were Indonesian, and not just Javanese, Maduran or Sumatran. They could see the importance of working together as Indonesians, whatever their religion and region. It is not surprising that Budi Utomo, the first modern Javanese organisation, was founded at the Indonesian medical school, STOVIA, in 1908. Later, in 1913, the radical Indies Party was born. It aimed to unite all Indonesians in one party and demanded full independence for Indonesia.

Abdul Rivai (1871–1937)

Abdul Rivai was born into a family of teachers. He studied medicine at the Dokter Djawa school from 1887 to 1895 then worked as a doctor and also did some translating and journalistic work.

In 1899, he went to the Netherlands to undertake further medical training. Obstacles were put in his way, as he had to study for a Dutch highschool leaving certificate before he could enter a Dutch university. His funds were running out so he published articles in various magazines to get some money. Some of these were critical of the colonial administration. He began a newspaper, and then, in 1902, with a Dutchman called Brousson, he started a publication Bintang Hindia. They told the government the journal was to educate Indonesians about the Netherlands, and for a number of years gained some funds to help to produce it. It was read widely among the educated classes of Indonesians, with up to 30 000 subscribers. The articles encouraged discussion of the need for education and progress for Indonesians. For example, Rivai wrote about the victory of Japan in the 1905 Russo-Japanese War:

So far the people of the white race, the spoilt pets of history, had regarded themselves as the sole lords and masters of the earth. The sudden appearance of a people of another race on the scene to defy one of the most powerful nations of the West with implements which, though adopted from them, it had perfected independently, seemed almost like an affront to them. They were not used to this. The fact remains even so. Willy-nilly, they will have to get used to prospecting Japan as a major power.

Rivai advised Europeans to stop putting themselves above other peoples and stop thinking only of enriching themselves at the expense of others:

It is a matter of urgent necessity that the white races finally accustom themselves to approaching people of other races without prejudice and without self-exultation, and that they finally stop letting the course of their politics, often influenced by the merchant and the mine-owner as it is, be determined by purely materialistic interests. Justice and fairness in the estimation of other people, that is what the future of Europe demands.

The journal campaigned for more Dutch language schools, more opportunities for Indonesians to study abroad, a rise in teachers’ salaries, and the opening of more government posts for Indonesians. His newspaper inspired other editors in Indonesia to set up similar papers.

Rivai wrote for a group of Indonesians whom he called kaum muda and described as, ‘all people of the Indies whether young or old who refuse to follow the ancient system, obsolete customs and outdated habits, but wish to obtain respect by way of knowledge and education’.

After his medical studies in the Netherlands, Rivai came back and probably worked as a doctor in Sumatra. He continued his support for progress in Indonesia, and in 1913 chaired the first branch of the Indies party in Sumatra.

RESEARCH 15.3

Raden Adjeng Kartini (1879–1904)

Raden Adjeng Kartini, the daughter of the governor of Jepara, attended school with Dutch girls and became fluent in Dutch. When she was 12 years old, as was the custom for women of her class, she had to withdraw from society and stay secluded in her father’s home and prepare for marriage. During this time she read widely, including the novel Max Havelaar, and wrote to a number of Dutch women friends. She expressed her ideas about the need to improve the position of women in her society and also her criticisms of the Dutch colonists who lorded their power over the local people. She was keen to study to become a teacher. She also wanted women to have the same opportunities to learn and study that were available to males. She criticised the suffering of secluded Javanese women, who were tied down by old-fashioned customs.

Her father was ill and wanted her to marry and, although she was opposed to the custom of polygamy, she became the fourth wife of another noble Javanese official. He supported her wish to set up a school for girls at their home. Sadly, she died soon after the birth of her son in 1904. She was only 25 years old.

Some years after her death, her letters were published under the title Letters from a Javanese Princess. This was a rather silly title, as Kartini did not emphasise her noble birth, but was interested in the needs of people of all classes. Like many of the kaum muda, Kartini resented the Dutch colonials who saw themselves as superior to the Indonesian people. Educated Indonesians were constantly reminded of their lowly status. She wrote about one young man, a brilliant student, who was humbled because he dared to speak in Dutch to a small-minded official. This official punished him by sending him to a lowly clerical job in a remote place to think over his misdeeds.

His new boss was like the worst Dutch colonists: ‘In many subtle ways they make us feel their dislike, “I am European, you are a Javanese” they seem to say, or “I am the master, you are the governed”.’

Kartini set an inspiring example as an early Indonesian nationalist and feminist. In 1964, President Sukarno declared that her birthday, 21 April, would be Kartini Day, a national holiday across Indonesia.

Towards the new Ethical Policy

Early in the twentieth century, the Dutch government developed new policies for the Dutch East Indies, known as the Ethical Policy. In 1898, Dr Conrad Théodoor van Deventer wrote an article entitled ‘A debt of honour’ and argued that the Netherlands should repay to the Indonesians the surplus millions it had taken, and that this should be spent on educational and economic opportunities in the colony. This humanitarian plea was also in the interests of Dutch capitalists, he argued, for if the standard of living of the Indonesian peasants grew, then they would buy many goods produced by Dutch manufacturing industries.

In 1901, the Dutch Queen Wilhelmina introduced the new ethical policy in high-minded terms:

As a Christian power, the Netherlands is obliged in the East Indian archipelago … to imbue the whole conduct of government with the consciousness that the Netherlands has a moral duty to fulfil towards the people of these regions.

Looking towards an independent Indonesia

By the end of the nineteenth century, the Dutch were strengthening their grip upon the Indonesian archipelago. With the end of the war in Aceh in 1908, the whole of present-day Indonesia was under Dutch control. The Dutch territories had reached their greatest extent, stretching over 3000 miles from Sumatra in the west to New Guinea in the east.

However, a new class of people was emerging.

These people had a modern outlook and were happy to take some ideas from the West and to use them for the progress of Indonesia. They did not want just to copy the Dutch or follow the old customs of the aristocracy. In the first decades of the twentieth century, they worked to make a new and independent Indonesia.