15.3 India

State of the nation during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries

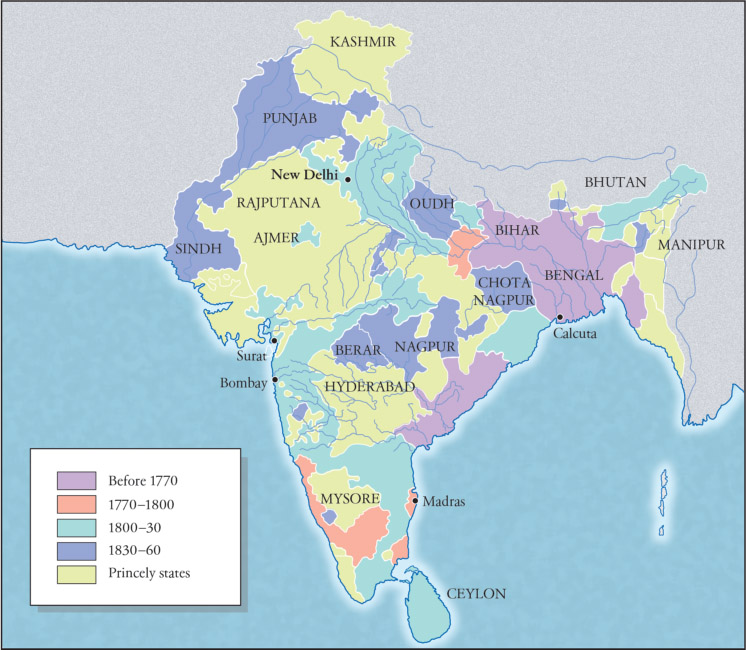

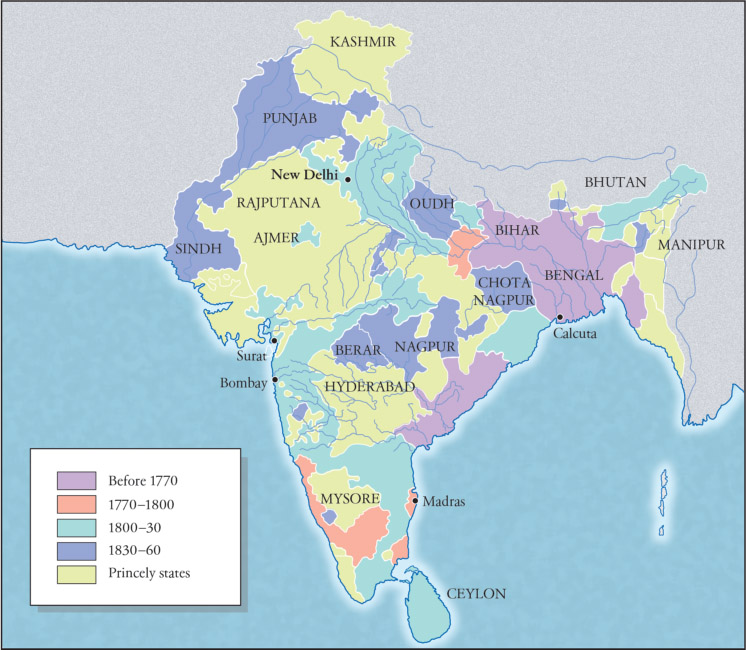

The East India Company was granted a charter by Queen Elizabeth I in 1600 to exploit the spice trade with the East. In 1608, the company set up its first trading station at Surat on the west coast of the Indian subcontinent. By 1750, the East India Company had established a foothold in the subcontinent, which expanded over the second half of the century, giving birth to the British Empire.

India had been ruled by the Mughal emperors from the sixteenth century. They did not have direct control over all of India, but ruled through various sultans, rajahs and nawabs who controlled their own kingdoms. By the eighteenth century, these local rulers were becoming more independent of the emperor.

Initially, the East India Company was focused on making profits, rather than gaining territorial or political control. In return for payment, local rulers granted them the right to trading stations and trading privileges. These rulers borrowed money from the East India Company and occasionally used company troops in their struggles with rival neighbours. Because of these negotiations, the company was gradually drawn into Indian politics, and company officials such as Robert Clive saw the opportunity for immense profits if they gained more political power.

The ruler of Bengal, Nawab Siraj Ud Daulah, was having a dispute with the company, which wanted to fortify its settlement at Calcutta.

In 1756, the nawab captured Calcutta and imprisoned many British citizens. However, Clive soon recaptured the city, but by using trickery rather than might. Before the Battle of Plassey, where the company forces faced the troops of the nawab, he made an agreement with Mir Jafar, the nawab’s commander, that the commander would lead many troops away from the battle and thus allow Clive to win. This was because Jafar wanted to become nawab himself. It is therefore not surprising that Clive won this battle in 1757, which placed this rich province virtually under British control. Clive’s own reward for his part in the battle was magnificent. The new nawab allowed him into the Bengal treasury full of gold, silver, jewels and money and he emerged with treasure worth more than £10 million today.

Clive saw that the British could become the governors of Bengal. In 1759, he advised the British Prime Minister that with a force of only 2000 Europeans it would be easy to get ‘the absolute possession of these rich kingdoms’. After further battles and political intrigues, the East India Company was made legal ruler of Bengal in 1765 and established their government administration.

The Indian peasants were required to pay high taxes, which were increased to 50% of the harvest value. The company also forced the growing of cash crops such as opium, jute and indigo, rather than rice. They particularly wanted to sell more opium to China to increase company profits there. The export of Indian opium to China led to the Opium Wars discussed earlier in this chapter. These policies led to the 1770 famine in which 10 million people, or a third of Bengal’s population, died.

Robert Clive had a pet Aldabra giant tortoise, named Adwaita, which was given to him in India in the 1750s or 1760s. In 1875 Adwaita was given to the zoo in Calcutta, where he finally died in 2006. At the time of his death, Adwaita’s age was estimated to be 255 years.

Change and continuity

In the late eighteenth century, the East India Company became a political force in India, extending its power from its bases in Madras and Bengal. In the south, it came into conflict with the state of Mysore and its commander-in-chief Haidar Ali, and his son Tipu Sultan. In 1792, the company defeated Tipu Sultan, who was later killed in 1799 when his capital was taken by the East India Company. The company also tightened its grip on the state of Oudh and imposed British power over the Marathas in the west, near Bombay (today known as Mumbai).

While Clive was extending the power of the company, other British officials were studying Indian cultures, religions and literature. Sir William Jones, a judge and accomplished linguist living in Calcutta (today known as Kolkata), was entranced by the richness of Indian cultures. In 1786, he wrote, ‘The Sanskrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either’.

Tipu Sultan employed up to 5000 men to send rockets containing blades over a distance of 2 kilometres into opposing forces. The British captured some of these rockets and successfully copied them. They later used them in the wars against the French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte.

Key event: First Indian War of Independence

In 1857, a revolt of Indian soldiers (known as sepoys) broke out across the provinces of central India. This widespread uprising, known by Indians as the First War of Independence, was a great blow to British power and led to great changes in India.

Christian missionaries were increasing their efforts to convert Indians to Christianity, and setting up schools to educate children about their religion. Some Indians were concerned about the criticism of their own religions. The sepoys, which made up the majority of the British forces in India, were dissatisfied with their wages and chances of promotion. When the army introduced new Enfield rifles, the soldiers had to bite off the end of the cartridge before the rifle could be fired. The sepoys believed that the cartridges had been greased with fat of cows and pigs. As Hindus do not eat beef and Muslims regard all pig meat as unclean, the sepoys feared this was a strategy to make them break religious teachings.

They saw this as part of a British plan to convert them all to Christianity.

Sepoys rose against their officers, murdering them and their families. The British authorities had no idea that this violent uprising was about to occur, nor that it would spread so quickly to major centres. Soon the rebels held Delhi, Lucknow, Kanpur, Bareilly and Jhansi. They proclaimed Bahadur Shah, the last of the Mughals, as the rightful emperor of India.

Acts of great cruelty were performed by both the British forces and the rebels.

Not all Indians joined the revolt, and with the help of Sikh soldiers from the Punjab region and Ghurkhas from Nepal, the British were able to regain control. At this time, Indians did not think of themselves as Indians, but rather as people from different regions and religions. This helps to explain why the revolt was not more successful.

In Britain, the news of the revolts and massacres made people ask why the East India Company, a private company, was governing such vast territories in India. After the tragic events of 1857, the British government moved for the Crown to take over the company’s territories and activities in India. In 1858, Queen Victoria issued a proclamation to ‘the Princes and Peoples of India’ promising equal rights between Indians and the British. Educated Indians also would be able to take up positions in the Indian Civil Service, an organisation of public servants or officials who did the day-to-day work of administering British India. However, Indians were only slowly admitted to the ICS, mainly to lowly positions.

Source 15.8a The First Indian War of Independence (04:26)

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 15.6

Position of India leading up to 1900

British India

In the later nineteenth century, the British authorities extended their power in India, taking over the Punjab region in 1849. Economic changes there led to some Punjabis coming to Australia to work as hawkers and in the sugar industry. The British fought expensive wars with Afghanistan, all paid for by Indian taxes. A railway system was extended over vast regions, along with a telegraph system that helped trade communications and enabled the government to control the population and to move troops quickly to trouble spots.

More British soldiers, officials, and planters and their families came to live in India. Although the British decided that, after the catastrophe of 1857, they would take care not to interfere with Indian customs and beliefs, missionaries continued their activities.

Other changes came in and Indians developed new ways of life. Universities were set up in Calcutta, Bombay and Madras (known today as Chennai) and Western-style schools grew up in many towns. Some Indian people went to study in Britain at Oxford, Cambridge and other universities. Mohandas Gandhi, the great Indian nationalist of the twentieth century, studied law in London from 1888 to 1891. Such Indian students learned much about British life and politics. For a while, Gandhi copied British ways – in his own words he played ‘the English gentleman’, wearing a top hat and tails – but he later become critical of some British ways.

Equal rights for Indian subjects?

From 1876, Queen Victoria was referred to as Empress of India. Indians who learned English and studied British politics observed that in Britain more people were gaining the right to vote, and wondered why, if they were ruled by the same queen, they also did not also have the right to vote. As Indians began publishing newspapers discussing Indian affairs, the government restricted the freedom of the press. Indians resented the greater privileges that the British enjoyed in India.

Many Britons at home and in India opposed ideas of equality with Indians. The British Empire was a system of foreign domination and India was governed in the interests of Britain and not of India. British industry benefited from cheap raw materials from India and the development of modern industry in India was largely neglected.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 15.7

Indian National Congress

In 1885, the Indian National Congress was established in Bombay by AO Hume, a retired British official, and a group of Indian men. It aimed to allow educated Indians to have a greater say in the government of India and in the Indian Civil Service. Wyomesh Chandra Bannerjee was president of the first meeting where 72 delegates met to discuss the way forward.

Soon the organisation became an important force in Indian politics, calling for more political rights for Indians and finally for independence from British rule. In 1901, Mohandas Gandhi, who had just returned from South Africa, went to his first Congress meeting. Later he was to become a key leader in the Congress and in the struggle for Indian independence. By 1901, Congress members were beginning to think of themselves as Indians united in the same struggle, rather than as people from different regions and religions with different interests.

RESEARCH 15.1

Use the internet or your school library to investigate the life of Mohandas Gandhi. Particularly focus on his early student days in London. How do you think his time in London influenced his future career with the Indian National Congress? He said he played at being and looking like an Englishman at this time. How do you think this influenced his ideas about Indian nationalism?