15.2 Japan

State of the nation during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries

In 1750, the symbolic ruler of Japan was the emperor, but it was in fact the shogun, a military dictator, who held power. The Tokugawa family held the title of shogun from 1603 to 1867. The Tokugawas unified Japan in 1600 and brought the daimyo under their control.

Daimyo were powerful lords who controlled large areas of land, but who owed their allegiance to the emperor and the shogun. The daimyo and their families were required to spend long periods in the capital Edo (now Tokyo) so that they would not plot against the shogun. This centralisation of power encouraged the growth of Edo, and by the end of the eighteenth century it was the largest city in the world, with more than 1 million residents.

Europeans, especially the Portuguese and Dutch, had been trading with Japan from the sixteenth century. In 1549, Francis Xavier, a Jesuit priest, arrived in Japan. As the number of converts to Christianity grew, Japanese rulers became increasingly concerned about the activities of foreign missionaries and merchants. They knew that the activities of merchants and priests had been the first step in making the Philippines a colony of Spain. During the sixteenth century, Christian converts began to be persecuted by the Japanese authorities. In 1626, Christianity was banned in Japan and by 1639 all Europeans had left the country except for the Dutch East India Company, which was allowed to remain on Dejima, a small artificial island in Nagasaki Harbour.

Mixing between the Dutch and the Japanese was strictly limited. Japanese were forbidden from travelling abroad and those who were overseas were prohibited from returning. For the next 250 years, Japan closed its doors to the rest of the world. This opposition to the foreigners helped to develop a feeling of Japanese nationalism and identity, but it also closed Japan to new ideas and new technologies.

Even though Japan cut itself off from the world, this was a period of change within the country.

It was a period of internal peace; and because the population was stable at around 30 million people, living conditions improved. Although the shogun wanted to freeze the social structure, a merchant class grew in the larger towns. The wealth they were amassing was to become useful later in the nineteenth century. The samurai were no longer needed to fight. Many became involved in civil administration and government work. Many more, however, became effectively unemployed – and because of the strict restrictions on the samurai class, they couldn’t get new work.

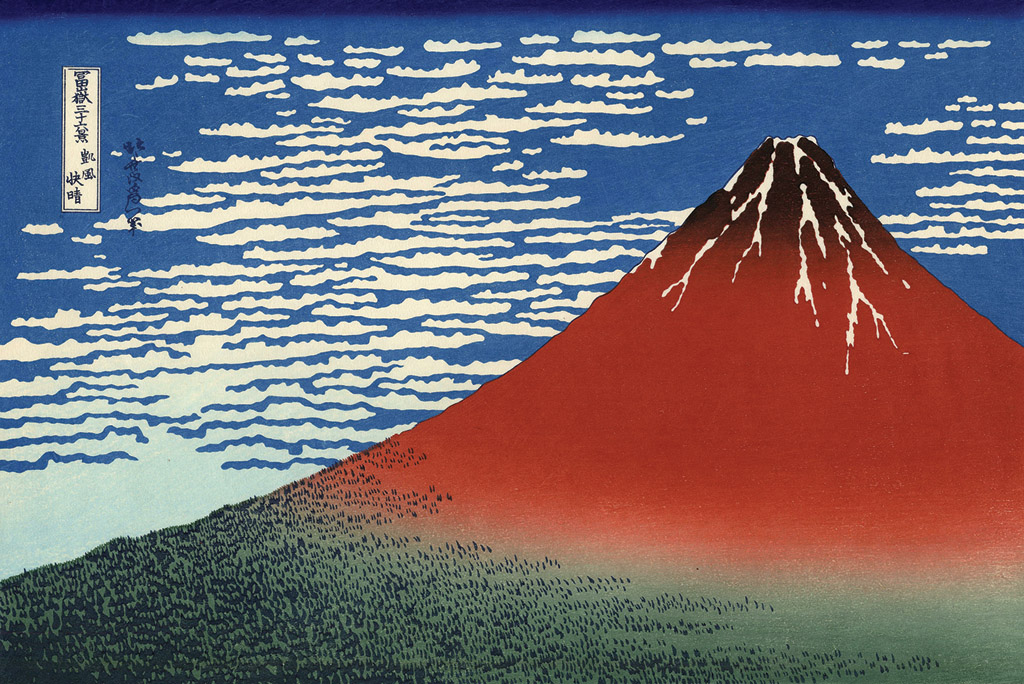

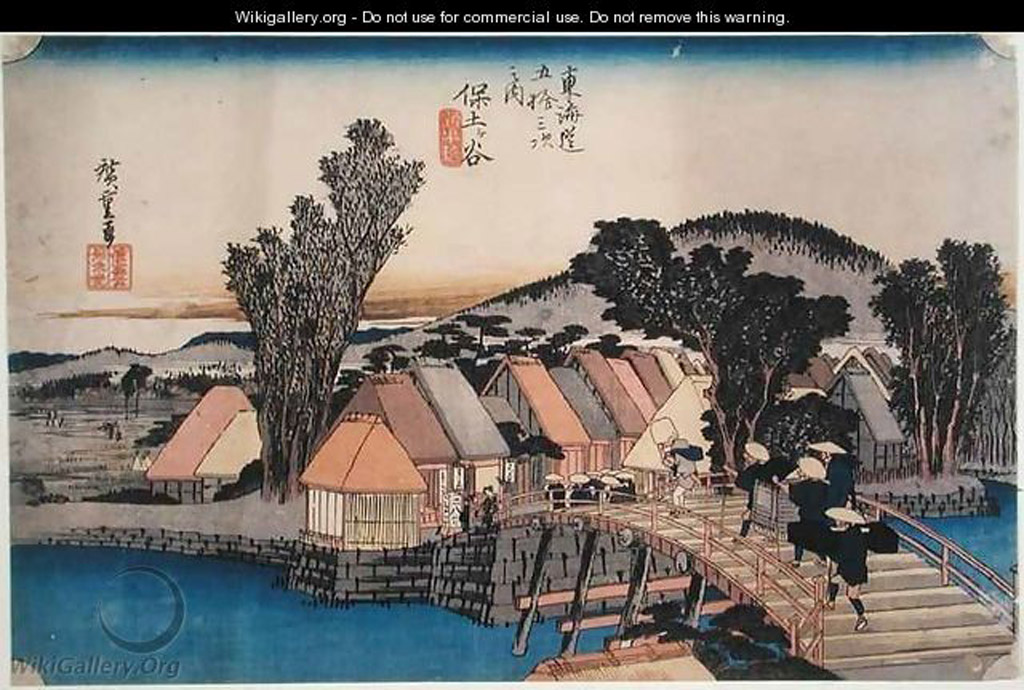

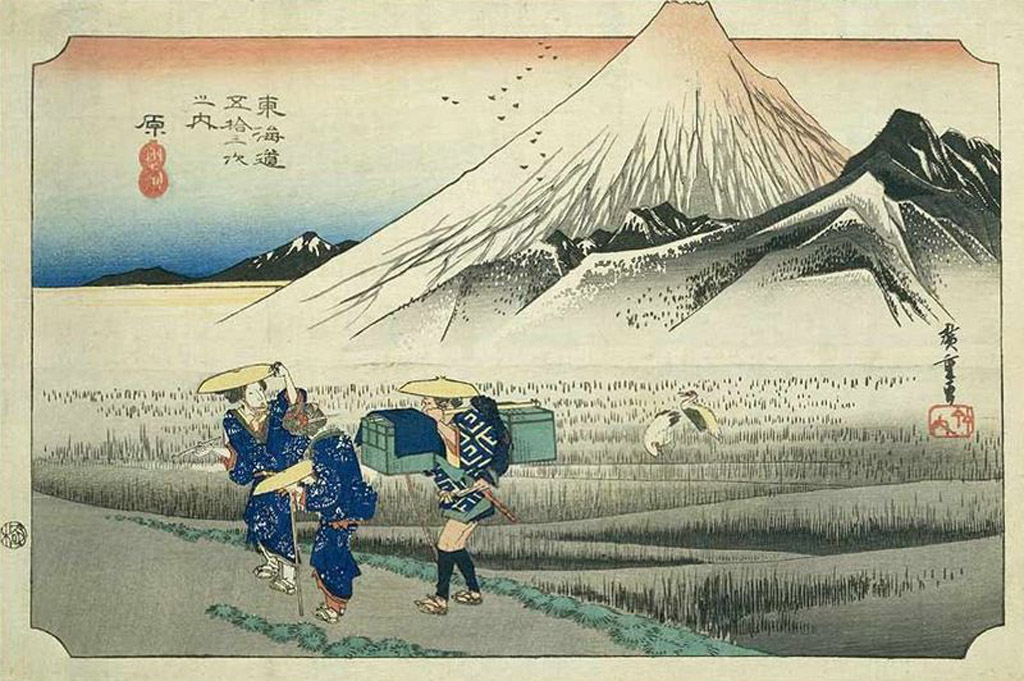

The rapid growth of Edo during this period led to the development of a new kind of urban culture. There was a rich artistic life, with theatre, poetry and visual art all flourishing. One of the most notable art forms was ukiyo-e, or woodblock printing. Famous artists included Utamaro, Hiroshige and Hokusai (see Source 15.5).

Edo society also began to explore Western philosophical, political and scientific ideas, which they were exposed to through the Dutch port of Dejima near Nagasaki. Hence, Western ideas became known as rangaku, or ‘Dutch learning’.

Change and continuity

Foreign devils are back!

With the Industrial Revolution and the growth of capitalism, European and American traders were spreading across the world seeking trading opportunities. From the late eighteenth century, a number of efforts were made to break into Japan, but these were repelled. Japan had witnessed the disasters that had befallen the Chinese with the onslaught of the Westerners. However, some Japanese leaders began to hold the view that Japan should combine ‘Eastern ethics’ and ‘Western science’. Many were critical of the poor response of the shogunate to a severe famine between 1833 and 1837. Dissatisfaction was growing as more people began to view the officials as corrupt and inefficient.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 15.4

- Explain why the Tokugawa shoguns become concerned about the growth of Christianity in Japan.

- In groups, discuss why you think the shogun asked the daimyo to spend long periods in Edo.

- On the internet or in the library, research ukiyo-e. What are some qualities of these paintings? Try to draw something in your classroom in the ukiyo-e style.

In July 1853, the US Commodore Matthew Perry steamed into Edo Bay with four ships.

He had orders from the President of the United States to seek the humane treatment of castaways and, most importantly, the opening of Japanese ports to trade. He made sure that the Japanese understood that the modern US ships were well armed, and presented a letter from the President.

He left saying he would return the next year for the Japanese answer to this diplomatic but forceful request.

The shogun did not know how to handle this unprecedented situation, but ultimately had no choice but to submit to these demands. On Perry’s return in February 1854 with eight ships, the shogun agreed to the opening of Japan under the terms of an unequal treaty, the Treaty of Kanagawa.

As with similar treaties with Britain, Russia, France and Holland, the Treaty of Kanagawa placed low tariffs on goods brought into the country by foreign merchants. The treaties also had clauses about extraterritoriality, which meant that foreigners were not subject to Japanese laws.

Now Western traders, eager to exploit and profit from the new Japanese trade agreement, entered the country. Their behaviour and arrogance was shocking to many Japanese people, who were very critical of the Tokugawa shogunate for failing to protect them, their country and its traditions from these crude interlopers. After all, the shogun was supposed to be the military protector of Japan.

Key event: the Meiji Restoration

Satsuma and Choshu, two of the outside daimyo and traditional rivals, decided to join together to oppose the shogun and to call for the reinstatement of the emperor as the rightful ruler of Japan. They convinced the emperor to decree the abolition of the shogunate in 1868.

The emperor was a 15-year-old boy, Mutsuhito, who was better known as the Meiji – a term that translates as ‘enlightened rule’. He was helped to make decisions by the samurai of Satsuma and Choshu.

The Japanese now had a breathing space to get on with the reforms and modernisation of their country, without too much interference from the West. Japan’s military was weak and it would have been easy for the Western powers to make the inroads they had made in China. But the Western nations were still heavily involved in China, so Japan was largely left alone.

However, the transition from the shogunate to the Meiji era was not all smooth sailing. There was a series of conflicts, most notably the Boshin War of 1868–69, which was fought between the supporters of Meiji and the supporters of the shogunate. Victory by the Meiji supporters allowed the new rulers to implement their reform program.

Edo, now renamed Tokyo (‘eastern capital’), was retained as the capital city of the new regime.

One of the first things the new government did was to issue the Charter Oath, which showed the different approach of the new government. New principles included:

- public discussion of all matters

- the participation of all classes in the administration of the country

- freedom for all persons to pursue their preferred occupation

- the abandoning of evil customs of the past

- the seeking of knowledge throughout the world in order to strengthen the country.

Position of Japan leading up to 1900

Economic development and modernisation

The Meiji government wanted to engage with the new Western ideas while maintaining Japanese ways. A popular slogan was ‘Japanese spirit, Western learning’. They hired many foreign technical advisers to help them in fields from mining and engineering to agriculture and education. Additionally, groups of officials were sent abroad to study and observe. One of the most important was the Iwakura Mission of 1871–72 (see Source 15.6), which sent 60 students overseas to complete their education. Five young women stayed in the United States, including Tsuda Umeko, who was only 7 years old.

When she had finished her studies she founded Tsuda College, a university college for women, which still exists today.

New modern systems assisted the development of the new Japanese economy. Railway construction connected major centres and made trade and transport more efficient. The first railway opened in 1872 and ran from Yokohama to Shinagawa and then on to Tokyo. By 1900, 5000 miles of track had been laid. Before, it had taken 2 weeks on foot to travel from Tokyo to Kyoto, but in the 1880s it could take 1 day on the railway.

The old social distinctions also were abolished.

The 1868 Charter Oath meant that people from all classes could enter any occupation. The old samurai class was phased out, as in theory the Meiji restoration gave every citizen equal opportunity. Universal education was proclaimed in 1872, but this took some time to achieve. In 1879, just two-thirds of boys and one-quarter of girls were attending school. At first the Japanese adopted everything Western in their new schools, but soon they realised the importance of maintaining traditional ways and values. Thus the schools, along with a new modern curriculum, began to teach students values of Confucianism, Shinto and nationalism.

As industry grew, many new companies were able to call upon some Japanese funds to support their ventures. Many, such as Mitsubishi, benefited from this close relationship with the government and over time developed into the powerful multinational corporations of today.

Moves to democracy?

Even though the Charter Oath had promised ‘public discussion of all matters’ and ‘the participation of all classes in the administration of the country’, the Meiji period saw political power concentrated in the hands of important advisers around the emperor. The cult of the emperor was developed, following a clause in the Meiji constitution that read, ‘The Emperor is sacred and inviolable’.

The Japanese developed a type of government that had some of the elements of democracy, such as elections, but which was weighted in favour of the powerful advisers to the emperor. The new constitution introduced in 1889 included a bicameral parliament, known as the Diet and modelled on the German parliament.

The upper house, the House of Peers, had nobles appointed to it and the Lower House was elected.

Only 2% of the male population had the vote, because of the requirement that voters pay at least 1 yen in tax per year. This eliminated all but the wealthiest members of society from the electoral system. The cabinet was not responsible to the parliament. It was an uneasy mixture of democracy and authoritarianism. A strong sense of nationalism was encouraged by the government.

Japanese imperialism and power

Like other capitalist nations, Japan was eager to expand in order to gain new sources of raw materials and new markets for its manufactured goods. The Japanese government and people also greatly resented the unequal treaties they had been forced to sign by Commodore Perry. By the late nineteenth century, they had managed to remove some of these unequal terms. However, this was the age of high imperialism, when European nations dominated much of the world’s people, and it was common for white people to assume that they were superior to the people of other nations they encountered. The Japanese particularly resented the idea that they, too, were seen as inferior. Japan wanted to be, and to be treated as, the equal of the leading nations.

Traditionally, Korea had been a vassal state of China, but Japan was concerned that Korea was a ‘dagger pointing at Japan’s heart’ and that this dagger might be used by some European colonisers. Japan tried to prevent this by increasing its influence in Korea, thus causing the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War, in which China was quickly defeated. Using naval tactics they learned from the British, Japan destroyed the Chinese fleet.

Source 15.6a A naval battle during the Sino-Japanese War. (00:21 - no audio)

Japan made China pay a huge indemnity and give up some territory. This was the beginning of Japan’s hoped-for empire in the East. But Germany, France and Russia stepped in, forcing Japan to return part of this territory to China.

The Japanese were furious, especially when a few years later these powers started taking over the same parts of China for themselves. The Sino-Japanese War had demonstrated the military might of Japan, but once again Western powers, especially Russia, had humiliated Japan.

However, Japan’s military expenditure was growing. From 1897, half the national budget went to the armed forces. The British recognised Japanese strength and negotiated a treaty: the Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1902, which was the first treaty of equality between an Asian and a European power in the modern era. This treaty meant that Japan and Britain would declare neutrality in the event that the other signatory became involved in war with another power, and would actively support the other signatory if they were involved in war with more than one power.

The Russian Trans-Siberian railway, the construction of the port of Vladivostok and Russian control of parts of China showed that Russian power was growing in the east. The Japanese wished to stem this Russian advance.

With the British committed to neutrality, in 1904 the Japanese waged war against the vast Russian empire. This led to great casualties on both sides, but the Japanese commanders were very successful, especially when they destroyed the Russian fleet in May 1905 in the Straits of Tsushima.

The defeat of a great European power by an Asian nation resounded around the world. It gave hope to the many colonised people in Asia and Africa. It also led the colonising powers to realise that the colonised peoples of the world could adopt modern technologies and challenge European and American dominance.

During the sakoku jidai (‘closed country period’), any foreign castaways who landed on Japan were likely to be executed. Some were luckier and were only expelled.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 15.5

- Research the Iwakura Mission and the life of Tsuda Umeko and present a poster on it to the class.

- On the internet, research Dejima and the interaction between the Dutch and Japanese people there. Draw a diagram of the island and make a poster about the interactions.

- Draw up a chronological chart with columns for China and Japan. Compare how each country was handling its relationships with the West during the period 1750–1900 and how this affected their autonomy.