14.4 Legislation 1901–14

Australia at Federation

Historians have found it hard to discover much enthusiasm by colonists in Australia for the six separate colonies to federate and become a Commonwealth in 1901. The proposal was decided by popular vote in a series of 10 referenda in 1898–1900. Voting was not yet compulsory and usually less than half of the registered electors – all male, adult property holders – even bothered to vote. For the most part, only between 30% and 43% favoured Federation. Victoria was the colony most enthusiastic about national union, and this was the only place where an actual majority voted in the affirmative, in 1899. Western Australia, worried about financial disadvantages, held out the longest – not holding its referendum until mid-1900. It was passed only due to the goldfields’ vote.

Many people tended to be apathetic; and some regarded Federation only as a business venture to dismantle customs barriers between the colonies in order to improve internal trade. A more idealistic minority, however, was moved by nationalistic feeling and looked towards Australia becoming ‘a mighty nation’ someday.

Yet the new Commonwealth was far from being an independent, sovereign nation in 1901.

It had no foreign policy separate from that of Britain. It could not declare war or peace. It was unable to make treaties with other nations and had no diplomatic standing abroad. It retained the British national anthem and its head of state remained the British monarch. The flag flown was the Union Jack. Even Australia’s domestic legislation could be ruled invalid by the British parliament, and its highest court of appeal was the British Privy Council. As historian Manning Clark observed, ‘There was no declaration of independence … No one seemed to be able to say who Australians were or what they stood for’. The new Australian states also jealously guarded their own powers and finances, thus further restricting central control.

At the Commonwealth inauguration ceremony in Sydney on 1 January 1901, British officials – politicians, churchmen and military figures – were prominent. A large crowd of more than 100 000 people watched the ceremony in Centennial Park and attended the procession through the highly decorated Sydney streets. The loudest cheers were reserved for the British Imperial soldiers: Queen Victoria’s Hussars, the Imperial Life Guards, Bengal Lancers and Indian Ghurkhas. Australian troops were fighting in British wars in South Africa and China at the time. But when the Commonwealth was proclaimed by Britain’s Lord Hopetoun, the press reported a crowd reaction of ‘Listless Apathy’. There was hardly a spontaneous cheer in the park. Assembled schoolchildren cheered on command and sang the ‘Federal Anthem’, but everyone else continued on with their picnics.

‘There was a meagre cheer, and Australia was born,’ the Sydney Bulletin stated. Less than 3 weeks later, Britain’s Queen Victoria died, casting a cloud of gloom over further proceedings.

Among the architects of Federation, only one man, Andrew Inglis Clark, was a republican. He was a shy, retiring person who worked hard on the Australian Constitution. But he was not a prominent speaker. The rest tended to see themselves as ‘children dependent on a superior people’ (to quote Sir Samuel Griffith). These ‘superior people’ lived in the British Isles. The founding fathers of Australia therefore regarded themselves as Britons first and Australians second.

All of Australia’s strength and national essence, it was widely believed, rested upon ‘the British connection’.

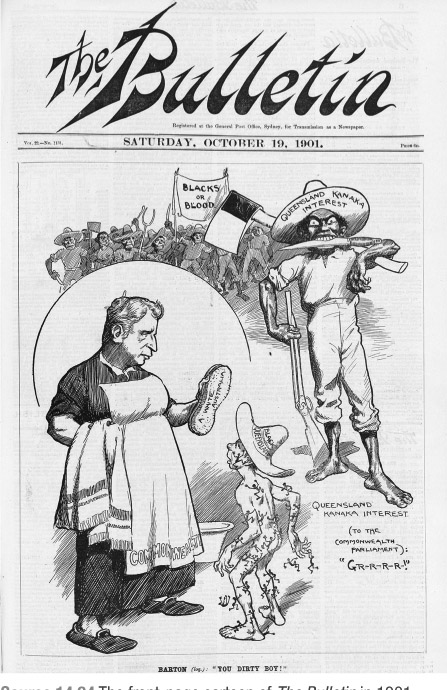

The White Australia Policy

The so-called ‘White Australia Policy’ cannot be traced to any single piece of legislation. Rather, it developed from a considerable number of parliamentary Acts of the new Australian Commonwealth, aimed at preventing non-white nationalities from migrating, removing certain non-whites already resident and severely restricting the rights and opportunities of others. It also concentrated early national defence measures on an expected Japanese military invasion, though no such invasion was contemplated by Japan.

Of all the Australian capital cities, Brisbane was the only one to vote against Federation in the referendum of 1899. There was great fear that local manufacturing and commerce would be swamped by stronger competition from Sydney and Melbourne.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 14.8

Examine Australia’s move to Federation and answer the following questions:

- Why was Australian Federation greeted with so much public apathy in 1901?

- Which groups were the most enthusiastic about Federation?

- What happened in Sydney on 1 January 1901?

- Was the Inauguration Ceremony more of a British than an Australian one?

- Why was the British connection so strong?

This approach arose from dominant concerns that we would now consider as racist: for example, the widespread belief that non-whites were both naturally servile and worth less as workers than whites.

Therefore, it was thought that non-whites would not agitate (as white labourers did) to improve their working situations or wage levels by forming trade unions and striking or negotiating for better pay and conditions. So, it was concluded that their migration would lower Australian wages and degrade working conditions generally. The migration of British and European light-skinned people was not similarly regarded.

Furthermore, racist theories of the time claimed that non-whites were also inferior intellectually, morally, sexually, culturally and socially. So, it was said that their presence in Australia led to degeneration, crime, immorality and disease.

Very few mainstream Australians disagreed with this viewpoint at the time. It was supported by widespread Western scientific, philosophical and religious beliefs.

In 1888, the separate Australian colonies had united to exclude further Chinese migration. In the 1890s, individual colonies – such as Western Australia (1897), New South Wales (1898) and Tasmania (1898) – adopted a blanket restriction of all non-Europeans. White protests in northern and western Queensland, rural New South Wales and Victoria, and the Western Australian goldfields had opposed the presence of even small numbers of Malay, Sri Lankan, Indian, Japanese, Melanesian and Syrian people.

Consequently, the first national issue addressed by the Commonwealth parliament in 1901 was the restriction of all non-white immigration.

The Immigration Restriction Act of December 1901 accomplished this by devising a so-called ‘Dictation Test’ to be given only to non-white migrants in such a form that they were doomed to fail it. This bogus test camouflaged the Act’s real racial intentions. This was done to address British concerns that an openly expressed racist ban would offend Indian Imperial subjects and the emerging Pacific industrial power of Japan.

Further, the Post and Telegraph Act 1901 prevented non-whites working on any ships carrying Australian mail, while the Pacific Island Labourers Act 1901 directed that all Melanesians be denied access to Australia from March 1904.

Melanesian sugar workers (known as ‘kanakas’) in Queensland and northern New South Wales were to be deported and repatriated to their islands from December 1906. Almost 7300 Islanders were removed between 1906 and 1914, while 1500 to 2000 managed to stay by obtaining exemptions or going into hiding.

The Naturalisation Act 1903 reserved British citizenship for whites only, while the Franchise Act 1902 withheld voting rights from non-whites and the Old Age Pensions Act 1909 and the Maternity Allowance Act 1912 denied them welfare benefits. Many pieces of state legislation, especially in Western Australia and Queensland, also adopted a ‘Dictation Test’ to restrict rights and opportunities on a racial basis.

The White Australia Policy was long regarded as the foundation stone of the new Australian nation. Its discriminatory provisions were not entirely removed from legislation until 1972.

Working life in the 1900s

What was it like to be an Australian wage-earner in the Federation era? The answer to this, of course, depends on the kind of work being done.

Was it skilled or unskilled? Rural or urban? And what was the status of the workers themselves? Were they members of a trade union? Were they male or female? Of European or non-European descent? Aboriginal or non-Aboriginal? Torres Strait Islander or non-Torres Strait Islander?

Generally, however, we can conclude that in this era the vast majority of people were ‘doing it tough’.

Early migration propaganda that encouraged poor labourers to come to the colonies had depicted Australia as ‘a working man’s paradise’. Yet this was rarely the case by 1900.

Trade-union organisation had only been legalised in the mid-1880s, but the new unions had then been almost destroyed in the 1890s strike wave by a forceful combination of employer groups and colonial governments. By 1906, only around 6% of the workforce was unionised. The long 1890s depression had also created around 30% unemployment in the skilled workforce.

It was even higher among the unskilled and there were no state welfare services to counter distress.

The Federation drought had also wreaked havoc on rural industries that employed one-third of the workforce. Although real wages between 1850 and 1890 usually had been higher than in Britain, they fell below the British average for most years between 1889 and 1908.

In most industries, weekly wages barely allowed for frugal survival. Skilled workers might earn up to 60 or 70 shillings (that is, $6 to $7) per week, but large families and high rents or mortgages usually accounted for most of this.

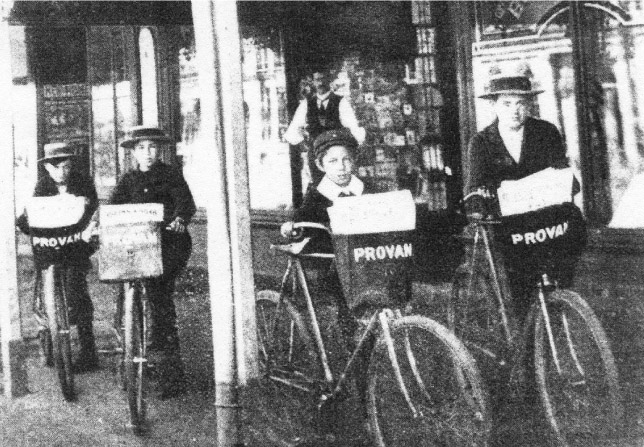

Most workers earned far less. Women workers, in particular, struggled to manage on less than 20 shillings ($2) per week. A female clothing worker, operating from her own home, might earn less than one cent per hour. This was called ‘sweating’. Child workers, selling newspapers on street corners for instance, received around 30 cents for a working week of 70 hours. There was no paid overtime, sick leave, holiday pay or superannuation. All such reforms had eventually to be won by trade-union struggle.

It was common for most people to work for more than 60 hours per week for such small wages. Factory workers laboured for 70 hours, usually in unhealthy and hazardous conditions.

Factories were insanitary, badly ventilated, poorly lit, loud and toxic, with no protection from dangerous machinery. Temperatures could be freezing during southern winters and more than 50°C in summer. Children as young as 12 years might work in such conditions.

Bakers and butchers worked up to 90 hours weekly; female bar attendants (called ‘barmaids’) and domestic servants performed their hard and dirty work for around 100 hours. Shop workers stood for up to 12 hours daily. Sitting down on the job could bring instant dismissal.

Indigenous workers were usually paid only with monotonous and nutritionally poor rations.

White employers often treated them brutally. If cash wages were granted, as in Queensland by the 1900s, the bulk of the money was taken by the state under the guise of ‘protection’. Queensland Aboriginal Protector, Archibald Meston, wrote in July 1900 that Aboriginal working conditions would ‘excite the horror of the Nation’. Their plight, however, was largely ignored by the early trade-union movement.

The Harvester judgement (1907)

The Australian Constitution did not grant the Commonwealth government any power to determine reasonable wages or tolerable workplace conditions. In order to sidestep this, federal parliament adopted an ingenious solution.

In 1906, it passed the Excise Tariff (Agricultural Machinery) Act. This imposed a tariff (or financial levy) on local machinery manufacturers. It would be removed, however, if the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration decided that a company was paying its workers a ‘fair and reasonable’ wage. In early 1907, workers at a company making agricultural machinery, known as Sunshine Harvesters, met at Braybrook in Melbourne to protest against the lack of overtime rates. Their employer, Hugh McKay, was Australia’s largest export manufacturer and owned factories employing more than 1000 men.

McKay argued that his weekly minimum wage of 36 shillings ($3.60) – or 6 shillings per day – was ‘fair and reasonable’. He had already applied for his exemption from the Commonwealth excise.

The Court of Conciliation and Arbitration decided to make the Sunshine Harvester Company a test case for the New Protection. Its recently appointed President, Henry Bournes Higgins, set about determining what a ‘fair and reasonable’ wage should be. He concluded that it should not be decided by what an employer said he could afford to pay or by what workers could extract from him by strikes or negotiation. Rather, it should be based on ‘the cost of living as a civilised being’.

In October and November 1907, Higgins listened to the evidence of workers’ wives about their household budgets. He wanted to know how much it cost for an average family of five members to meet the ‘normal needs’ of ‘a human being in a civilised society’. These needs included food, shelter, clothing and warmth. They also included, Higgins decided, such items as furniture, utensils, insurance, books and newspapers, tram and train fares, schooling needs, amusements and holidays.

Overall, the judge concluded, this minimum or basic wage should be 42 shillings ($4.20) a week or 7 shillings (70 cents) per day. This was significantly higher than McKay’s minimum wage and similar to the amount that colonial trade union leaders had earlier demanded for their members. If a company could not afford it, Higgins argued, it should probably be shut down as inefficient. Australia had thus established the first basic wage in the world. It would be many decades before other countries followed suit.

Yet the ruling applied to only one sector of the population. White male workers were granted this payment whether they had a family to support or not; neither was the size of the family taken into account. Females were not defined as family bread-winners (even when they were) and continued to receive lower wages – usually around 54% of a man’s. Aboriginal people, Torres Strait Islander people and many other non-white workers similarly did not qualify, and continued to live precariously.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 14.9

Consider the Harvester judgement and answer the following questions:

- What do you understand by the term ‘the New Protection’?

- Why was the Harvester Company chosen as a test case?

- How did Higgins determine what an Australian basic wage should be?

- Why were women, Aboriginal people, Torres Strait Islander people and non-whites excluded from this ‘social right’?

Hugh McKay later succeeded in having the excise Act ruled unconstitutional, but Higgins continued to use his basic wage finding as a yardstick in determining the outcome of industrial wage disputes.

How people lived at Federation

By 1910, almost 40% of Australians lived in the six capital cities. There were also more than 30 towns with populations between 10 000 and 30 000 people. Even smaller centres, however, supported a rich local culture. Bathurst, with a population of 9223 in 1901, produced three local newspapers.

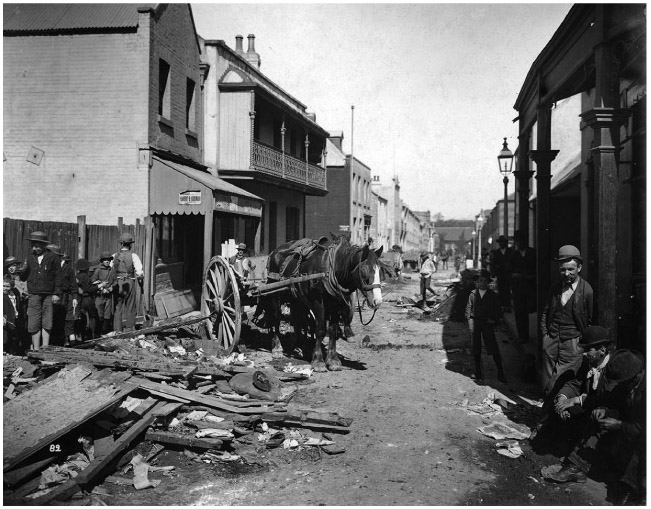

Australia was highly urbanised and, in these cities and towns, people lived in differing circumstances according to their wealth or poverty. A rich man, such as Thomas Holt of Marrickville, Sydney, occupied a mansion of 30 rooms, including a banqueting hall, ballroom and art gallery, which was maintained by a range of specialised servants. This contrasts dramatically with great numbers of urban poor who lived in overcrowded, run-down tenement slums in the inner city, and had to face inferior sanitation, bad health, unemployment and high infant mortality.

Bubonic plague, spread by the fleas of the black rat, broke out in these conditions across certain mainland cities from 1900.

In Collingwood or Fitzroy in Melbourne, as many as six people might live in one small room, while families of up to 12 people were crammed into unsewered, two- or three-room hovels. Most people lived in rented accommodation. Home ownership, for around two-thirds of the population, was an impossible dream.

Until 1905, many country people, struggling under drought conditions, survived on damper, ‘pie-melon jam’ and the rabbits they caught.

Dripping, golden syrup and condensed milk were rare joys. Schooling was meagre for farming families and English literacy was low.

There was little time for leisure activity. Men, women and children on most farms worked incessantly for survival. ‘We are just white slaves,’ one farmer’s wife explained.

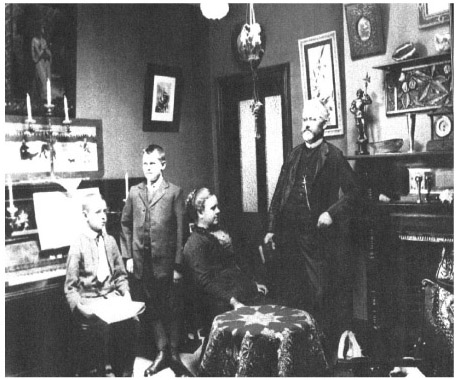

Between the two extremes of wealth and poverty, a minority of middle-class people – the families of skilled workers, tradesmen and the self-employed – were increasingly moving into suburban areas between city centres and the bush. Here they lived in more comfortable, detached houses on quarter-acre blocks.

Public transport, telephones, gas and electricity all made life easier from the 1890s. In these homes, labour-saving technology was gradually replacing domestic servants. Motor vehicles began their slow appearance from 1897. By 1914, there were still only 37 000 registered motorcycles, cars and trucks in Australia. People tended to view a car as a kind of mechanical horse.

In the schools, corporal punishment was widespread. People who wrote memoirs about this time recall teachers stalking around classrooms ‘in frock coats always with cane in hand’. Eighteen strokes was the punishment for ‘playing the wag’; that is, truancy. At All Saints Grammar in Melbourne, the headmaster daily ‘flogged not only the boys who wilfully misbehaved but also those … slow to learn’. Yet it was found in New South Wales that more than half the children described as ‘dull’ were actually suffering a health defect, such as poor hearing or sight. In Queensland, one-third of pupils had some physical complaint and 97% had decayed teeth. Those children who were left-handed were forced to write right-handed; some had their left hand tied behind their back, while others had their left hand caned repeatedly.

Due to poor diet and deprived living conditions, the average 14-year-old by 1910 was around 150 centimetres tall and weighed only 40 kilograms. The median life expectancy for white people was only 55 years for women and 53 for men.

Establishing state welfare

The new colonial societies in Australia were all built on hard work. Schoolchildren were taught, ‘It’s your duty to work. If you don’t work, you’ll starve.’ Dropping out of the workforce due to misfortune, illness or physical incapacity was often blamed on some individual moral failing.

For instance, it might be said that the person drank too much alcohol, was lazy or too self-indulgent.

Though people in distress might be offered some temporary, private charity, it was not considered to be the state’s role to help them survive in society in any permanent way. These social failures were branded as the ‘undeserving poor’ and were either left to their own devices or segregated in state-run asylums (or prisons).

Society, it was believed, needed to be protected from them, rather than the opposite.

The widespread suffering of the 1890s, however, encouraged a serious rethink of public policy. The bank crashes and parched inland taught many that even sober, thrifty citizens could be economically ruined through no fault of their own. Electors began demanding official protection and intervention against inequality, poverty, injury, illness and old-age privation for people of European descent.

In 1904, Australians elected the first national Labor government in the world. While its tenure was brief, its platform included state welfare as a citizen’s right. In 1908–09 and 1910–13, Labor returned to office for more extended terms. In 1908–09, in cooperation with Alfred Deakin’s Liberals, Labor introduced the Old Age and Invalid Pensions Act. In 1912, a maternity bonus for new mothers was added, but not for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Viewed from today’s perspective, such beginnings appear small and cautious. There was no attempt to introduce unemployment benefits or any educational or health initiatives.

Yet, for the time, along with arbitration and the basic wage, it was a big step forward. As a result, Australia was seen internationally as being a boldly experimental ‘social laboratory’, where a national safety net was now being woven to save the less fortunate.

The old age pension, introduced in July 1909, granted 10 shillings ($1) per week for women over 60 years and for men over 65. It was seen as ‘a just reward for a lifetime of useful work’. Yet it was not sufficient for survival and was also means-tested: payment ceased if the recipient earned 20 shillings ($2) or more weekly. A character test required the receiver to have been ‘sober and respectable’ for the past 5 years and free of criminal conviction for 12. Nevertheless, this pension was double the British equivalent, which was only available to those aged over 70 years. The invalid pension was also small and difficult to obtain. The applicant had to demonstrate a permanent incapacity and an absence of all family support.

Labor’s maternity bonus was its only welfare reform introduced between 1910 and 1913.

Each white mother (whether married or not) was granted a 100 shilling ($10) bonus for every live delivery. The average birth rate had fallen from seven children per family in 1891 to just over five by 1911 and there was great concern about ‘national decline’. There was official talk of women’s ‘selfishness’ in using birth-control methods and of ‘racial decay’ connected to a fear of Japanese invasion. The allowance was therefore a financial incentive to procreate and boost population growth. However, the national birth rate continued to fall, reaching a low of 1.5 per family in 1931.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 14.10

Recall Australia’s adoption of state welfare policies and answer the following questions:

- Why did people believe that poverty was the outcome of moral failure?

- How did this opinion change?

- What role did the Labor and Liberal parties play in the Federation welfare reforms?

- How important were the changes from an international perspective?

- How helpful were the old-age and invalid pensions of 1909?

- What were the reasons behind the maternity bonus of 1912?

- Why were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people excluded from these reforms?