14.3 Australian self-government and democracy

When the Australian colonies were founded, ordinary people had no chance to elect or even to influence their government. Each Australian colony was ruled by a governor appointed by the British government. The governors had to take orders from the British government, but as Britain was so far away they often made their own decisions.

As the number of free settlers increased from the 1820s, along with growing numbers of people who had finished their term as convicts (emancipists), some came to believe that they should have some say in the government.

During the nineteenth century, the Australian colonies developed the most advanced democratic political systems of the age. By the end of the century, Australian people had introduced most of the democratic reforms that followers of Chartism had unsuccessfully sought in Britain.

Initially, the British government created a committee that could advise each governor. In New South Wales, this was the Legislative Council, appointed in 1823. However, the colonists did not elect either the governor or the members of the Legislative Council. Only in 1842, with the New South Wales Constitution Act, were some New South Welshmen able to elect 24, or two-thirds, of the members of the Legislative Council.

There was a restricted property franchise, which meant that only those with a substantial amount of property were eligible to vote. Only they were seen as responsible people who could be trusted to vote sensibly.

The other 12 members of the Council were appointed by the Crown. This was the beginning of representative government in Australia. Gradually other colonies also gained the right to vote for some members of a Legislative Council, or an advisory committee to the governor.

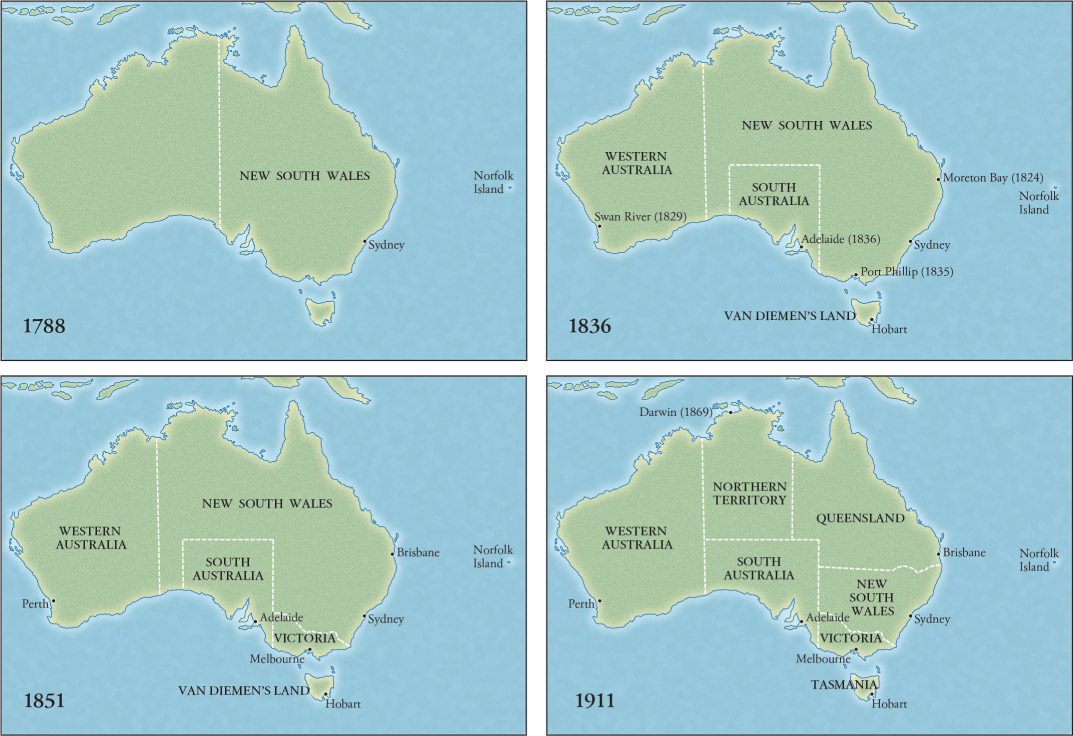

In the 1820s and 1830s, Australian society was changing with more free settlers arriving. In 1836, South Australia was established for free settlers only. In eastern Australia, there was a campaign to end the transportation of convicts and to promote a society of free people. Increasingly, Australian settlers wanted to rule themselves and to have some control over government spending. The settlers at Port Phillip (Melbourne) wanted their own separate colony.

In Britain itself, political ideas and institutions were changing. The British Reform Act of 1832 granted middle-class men the right to vote for parliament. The Australian settlers wanted the same right, and in 1850 the British government passed the Australian Constitutions Act, which made it possible for the colonies to move towards responsible government, or self-government with bicameral parliaments. Under this Act, Victoria became a separate colony.

During the early 1850s, politicians and lawyers in all the colonies (except Western Australia) were busy writing new constitutions. During these years, half a million free settlers flocked to Victoria. Many also went to the diggings in New South Wales. The gold rushes attracted thousands of miners from Britain, China, European countries and the United States. Within a decade, the population of New South Wales, South Australia and Queensland doubled, while in Victoria the population increased sevenfold.

Many of these migrants were young, and new radical and liberal political ideas were discussed and shared on the diggings.

The colonists’ confidence grew alongside the wealth of the country. Some made a fortune by finding gold, while others prospered by growing food for the miners, running coaches, setting up stores or building the houses, roads and many fine public buildings that grew up in the mining districts and in Melbourne. A feeling of being Australian was growing and some felt irritated by the continuing power of British authorities.

In 1853 William Wentworth, a wealthy politician in New South Wales, suggested that Australia should have a colonial peerage drawn from wealthy landowners. The radical Sydney lawyer Daniel Deniehy ridiculed the suggestion, calling it a ‘Bunyip aristocracy’.

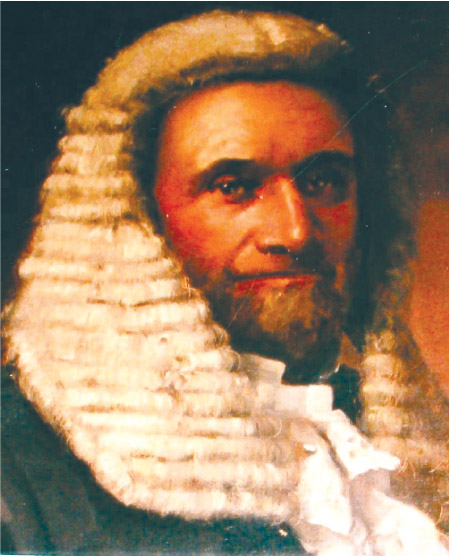

Eureka Stockade

In 1854, on the goldfields at Ballarat in Victoria, the miners’ resentment of the heavy mining licence fees and the way that the local police exercised their power as they inspected miners’ licences boiled over into a rebellion. A number of their leaders had been in the Chartist movement in Britain. The miners wanted to reduce or even end the licence fees and the tax on gold, and they wanted the vote.

In November 1854, the miners formed the Ballarat Reform League and agreed ‘that it is the inalienable right of every citizen to have a voice in making the laws he is called on to obey, that taxation without representation is tyranny’. They tried to negotiate their demands with Goldfields Commissioner Robert Rede and Victorian Governor Sir Charles Hotham. Rede did not want to compromise and ordered the police to continue to check miners’ licences.

The angry miners elected a radical Irishman, Peter Lalor, as their leader. Under the Eureka Southern Cross flag, they vowed to burn their licences and defy the government. They made a fort, or stockade, armed themselves and trained for battle. But when the more numerous government forces attacked them early in the morning on Sunday 3 December 1854, they were easily defeated. Twenty-two miners were killed.

The ringleaders were charged with high treason, but there was great public sympathy for them. Many Victorians were shocked by the government’s brutal actions and the juries refused to convict the arrested men. When they were freed, thousands cheered. An inquiry into the event suggested that the miners had justified grievances.

Rights or a riot?

People still disagree about the importance of the Eureka stockade in Australian history. Some believe that it was the real beginning of Australian independence and democracy. In 2004, Victorian Premier Steve Bracks said, ‘Eureka was about the struggle for basic democratic rights. It was not about a riot – it was about rights’. Today you see the Eureka flag being used by some groups as a symbol of their rebellion against authority.

They see it as an expression of true Australian democracy. Others see Eureka as just a riot by a small number of miners, arguing that only about 15% of the miners were involved in the stockade. They also point out that most of the leaders and those put on trial were from Ireland and the United States.

In fact, the process of writing new and more democratic constitutions for the colonies was well underway by 1854. New South Wales, Victoria and Tasmania (formerly Van Diemen’s Land) all had new constitutions in 1855. The South Australian constitution of 1856 was the most advanced democratic constitution in the world at that time. It introduced manhood suffrage for the lower house and a fully elected upper house, based on a property franchise. In the spirit of Eureka, the new Victorian parliament soon legislated for manhood suffrage as well. In 1856, South Australia, Victoria and Tasmania introduced another important democratic reform, the secret ballot. This meant that others could not discover which candidate you were voting for, which lessened the likelihood of the intimidation of voters by employers and other powerful people.

This more democratic system of casting your vote was one of the demands of the British Chartists.

The secret ballot was known throughout the world as the ‘Australian ballot’. Later, other countries (for example, Britain in 1872 and the United States after 1884) followed the Australian example.

Now these colonies had responsible government, elected by the people. In 1859, Queensland became a separate colony from New South Wales and began developing more democratic constitutions. Only Western Australia lagged behind, finally getting a new constitution in 1890.

Based upon manhood suffrage, these constitutions were among the most democratic in the world for their time, but generally they still denied Indigenous people and women the vote.

Unlock the lands

By 1860, manhood suffrage was accepted in most of Australia, and the colonial governments were largely independent of the British Crown.

However, miners, town workers and many voters opposed the dominance of the wealthy landed class of squatters and pastoralists in colonial politics and society.

From the 1860s, colonial parliaments passed Selector Acts. They wanted to unlock the vast land-holdings, which squatters leased from the government, to allow people of average means to select or choose land for farming. The selectors would be able to pay for the land over a number of years. It was believed that if the economic power of the large squatters was limited, then the colonies would be more equal and more democratic. Of course, the squatters opposed these laws and did all they could to hold on to as much of their land as possible. However, especially in Victoria and South Australia, a new class of freeholders with small to medium-sized family farms was created.

One of the last democratic reforms adopted in nineteenth-century Australia was the payment of members of parliament. This was first legislated in Victoria in 1870 and later in other colonies. This meant that even ordinary wage earners could stand for parliament, because they would receive a salary if elected. Now you did not need to be a wealthy man to be a member of parliament.

Position of women

In the mid-nineteenth century, women in Australia had many responsibilities to their families, but few political, social or economic rights. Though many women ran small businesses, kept shops or were domestic servants or teachers, many more were dependent upon men – their fathers and husbands. A woman had no legal protection if her husband was violent, did not support her and their children, or took her property. Australian women, like feminist women in other countries, organised campaigns to get educational opportunities, more paid work and access to divorce, as well as the right to keep their own property after marriage, to control their own bodies and to have access to birth control. To achieve this they wanted the parliamentary vote. They were concerned by male drunkenness and violence towards women and children, and wanted to care for women prisoners and other such unfortunates.

Women organising

Women created various organisations that all aimed to improve women’s positions, although with different emphases. From 1882, the Australian branches of the international Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) worked to protect women, children and family life. They aimed to control or abolish the liquor trade so that men would not waste their money on drink, beat their wives and leave them and their children in poverty and destitution. Women in both the country and cities joined the WCTU.

In 1884, Henrietta Dugdale and Anne Lowe formed the Victorian Women’s Suffrage Society, and similar societies grew in other colonies.

These had liberal ideas, believing that women, like men, should have human rights, citizenship and the vote. They also wanted equal justice, equal privileges in marriage and divorce, rights to property and the custody of children in divorce.

Working women, such as tailors, organised trade unions from 1882, seeking better pay and working conditions.

Some men supported their claims, but women had to persuade male voters and legislators in each colony. Many believed that women were less intelligent than men and should be only occupied with family life. Feminist women wrote letters to the press, organised petitions, made deputations to politicians and addressed meetings.

Louisa Lawson published The Dawn: a Journal for Australian Women from 1888 to 1905.

She wrote, ‘Men legislate on divorce, on hours of labour, and many other questions intimately affecting women, but neither ask nor know the wishes of those whose lives and happiness are most concerned’.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 14.6

The monster petition

In 1891, Victorian women went door-to-door and collected 30 000 signatures from women and men in favour of female enfranchisement and presented it to the Victorian parliament, but it denied their claims. A similar South Australian petition of 1894 had 11 600 signatures, while the Tasmanian women gathered 9500 signatures for three petitions between 1896 and 1898.

Queensland women gathered 15 366 signatures between 1894 and 1897.

In this video on the Arts Victoria website, Diane Gardiner, Manager of Community Access at the Public Records Office, talks about the monster petition: https://www.cambridge.edu.au/redirect/?id=220

Victories

In 1894, South Australian women aged over 21 years gained the right to vote and to stand for parliament. This was a world first; in 1893 women were enfranchised in New Zealand, but were not granted the right to stand for parliament.

Women gained the right to vote in other colonial or state elections in Western Australia in 1899, New South Wales in 1902, Tasmania in 1903, and Queensland and Victoria in 1908. With Federation in 1901, women gained the vote for the Australian Commonwealth parliament. It was a great victory, but Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in some states were excluded.

Moving towards Federation

During the later nineteenth century, some Australians began to think about an Australian nation. Communications such as railways and telegraphs meant that the colonies could be in close touch with each other. As people visited other colonies they realised that they had a lot in common. Some organisations like the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (1891) and the trade union movement (1879) formed national associations.

Businessmen saw that their Australian markets were divided by colonial borders and customs charges. It made more sense to have one nation, and thus one market for their goods. As we have seen in this chapter, anti-Chinese prejudices were growing, fanned by some politicians. There was the idea that Australia should be a white nation, prohibiting migrants from Asia, Africa and the Pacific Islands. Some believed that the need to defend Australia from foreign forces should lead to a federation. There were numbers of different reasons for supporting federation of the Australian colonies. The matter was discussed first in 1888, but did not proceed quickly. In 1889, Sir Henry Parkes made an impassioned speech at Tenterfield on the New South Wales–Queensland border calling for a federal convention to devise ‘a great national Government for all Australia’.

-

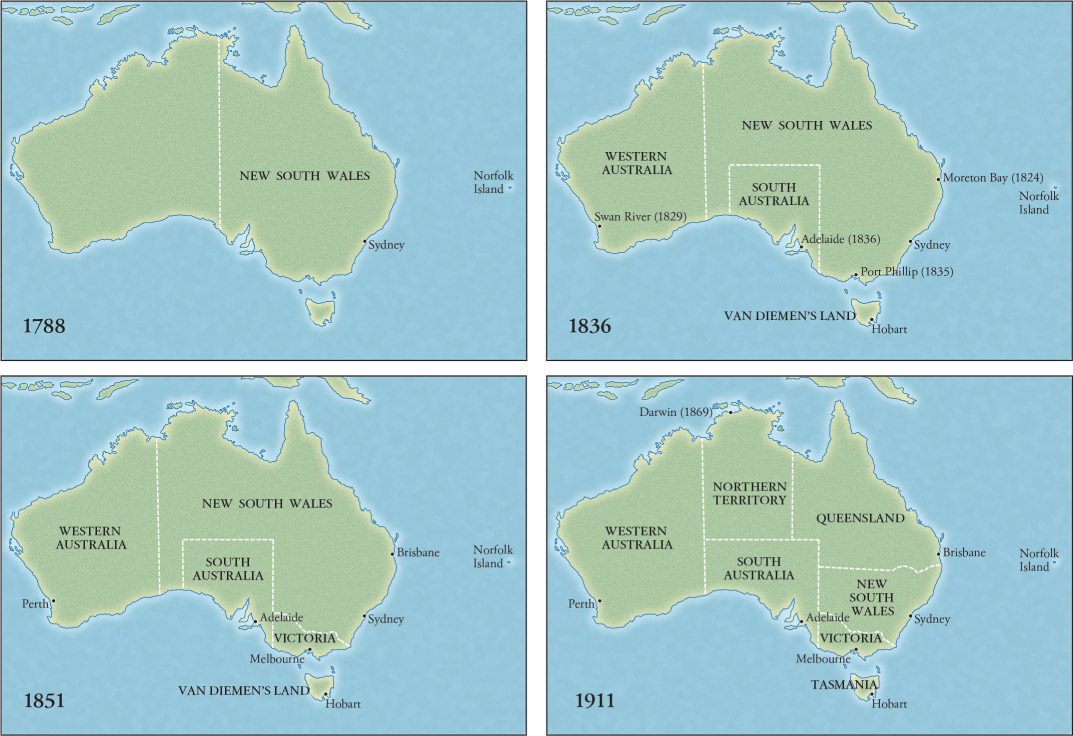

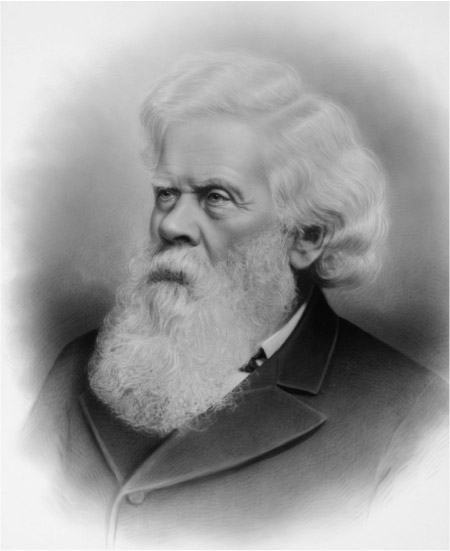

Source 14.21 Henry Parkes (1815–1896) worked as a labourer when he first arrived as an assisted immigrant in New South Wales in 1839. He enjoyed the great opportunities open to white men in Australia, becoming a newspaper editor and a liberal representative to the first colonial parliament in 1856. He served as New South Wales Premier five times and was knighted in 1877. Known as the ‘Father of Federation’, he died 5 years before the new nation was born. -

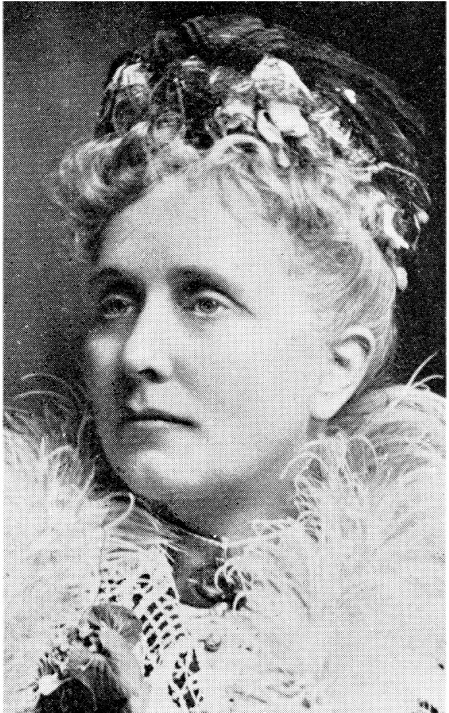

Source 14.22 South Australian Catherine Helen Spence (1829–1910) stood as a delegate to the 1897 National Australasian Convention. She was the first woman to run for election in Australia. She was not elected.

In 1891, the colonies were represented at the National Australasian Convention in Sydney, where they agreed upon the name ‘Commonwealth of Australia’. Some political leaders were in favour and others against, and still others regularly changed their minds. There were several conventions about the proposed constitution for the new nation. In 1897, delegates from five colonies were elected to discuss the proposition at the National Australasian Convention. Referenda were held in 1898 and 1899, and finally the ‘Commonwealth of Australia’ came into being in 1901.

Rights denied

As most Australian citizens were gaining political and social rights, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were becoming more disempowered than ever. From the 1840s, many Aboriginal people were living on mission stations run by various Christian denominations. Here they were protected from the physical violence meted out to them by settlers, but they found it difficult to maintain their languages and their cultures. These mission stations were run as dictatorships, with most power being held by the leading male missionary.

Bessie Cameron (c. 1851–95) was a Nyungar woman from Western Australia who studied in European schools there and in Sydney. She was a teacher at the Ramahyuck mission in Gippsland in Victoria, which was run by the Rev F. A. Hagenauer. He ran the mission in a very strict manner and made Bessie marry Donald Cameron, a man with mixed Aboriginal and Scottish descent. They had eight children and ran the mission’s boarding school. In 1886, Alfred Deakin and the Victorian government passed a law that meant that Aboriginal people of mixed descent could no longer live on mission stations. This saw many families like Bessie’s split up. Thus, as other Australians gained the right to vote and stand for election, Aboriginal families were losing basic rights, such as keeping their children with them.

Ngarrindjeri people at the Point McLeay mission in South Australia voted in the 1896 South Australian election and for delegates for the 1897 Federal Convention and the Federation referenda of 1898–99. However, most Aboriginal people were not on electoral rolls and were unable to take part in the political life of the nation.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 14.7

-

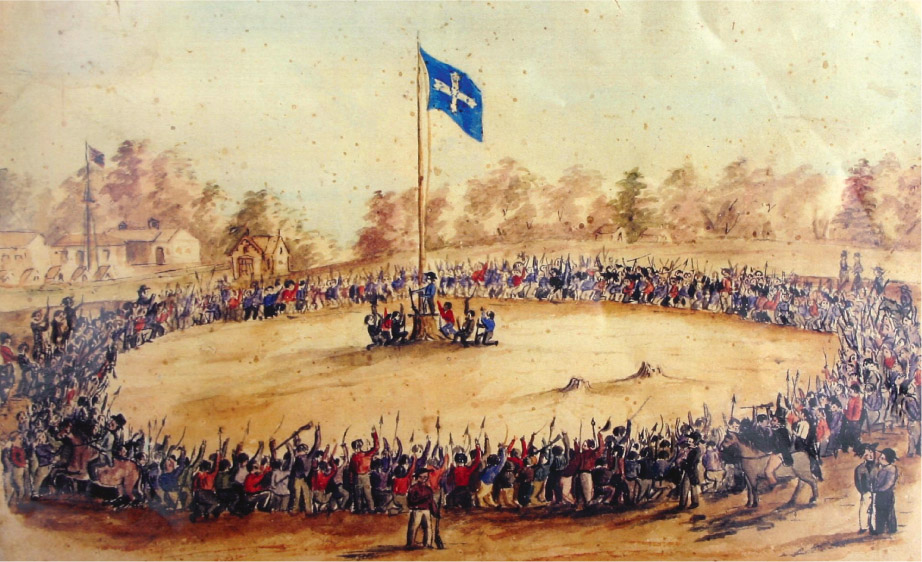

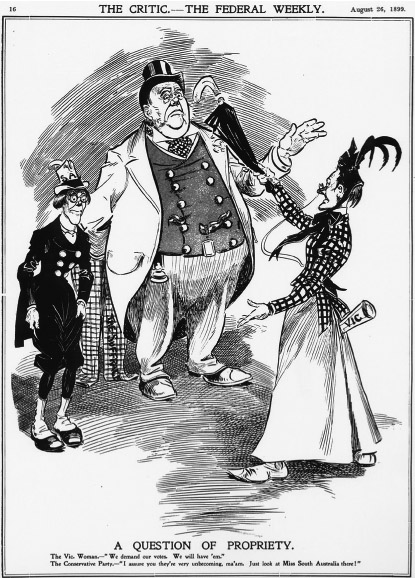

Examine Source 14.23 and answer the following questions:

- Why do you think the cartoonist has made Miss South Australia and the Victorian woman look ugly?

- Why do you think the cartoonist has drawn ‘the suffrage’ as a pair of trousers?

- How does the cartoon represent the male figure?

- With female political leaders at both state and federal levels today, what do you think about this cartoon drawn more than 100 years ago?

-

Source 14.23 The cartoonist shows a man representing the Conservative Party holding suffrage as a pair of trousers behind him. The Victorian woman is demanding the right to vote, but the man advises against it, pointing out that they ‘are very unbecoming ma’am. Just look at Miss South Australia there!’