14.2 Experiences of non-Europeans in Australia

During the nineteenth century, Europeans took up the idea that they were superior to people from non-European backgrounds. The idea of ‘race’ and supposed racial differences in character became more important at this time. A number of people who came to live in Australia were from non-European backgrounds. Because of the racial prejudices, which grew among Australians of European backgrounds, life could be very difficult for South Sea Islander, Chinese, Afghan, Japanese and Indian people, among others, who lived and worked in Australia before 1901. Today we recognise that they made important contributions to Australia and can be seen as pioneers of modern, multicultural Australian society.

South Sea Islanders in Australia

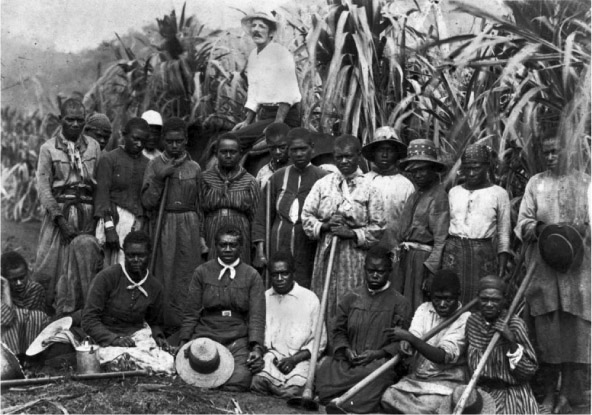

Around 60 000 South Sea Islanders came to Queensland and northern New South Wales between the 1860s and 1904. Those who came to Queensland in the 1860s and 1870s were usually captured by unscrupulous slave traders and taken from their islands in the Pacific. Christian missionaries and others were shocked by the cruel treatment meted out to the Islanders and urged the Queensland and the British governments to end this slave trade.

Some efforts were made to regulate the trade with the passing of the Polynesian Labourers Act 1868 and the Pacific Labourers Act 1880. Conditions improved very slowly.

The first arrivals had to learn some English.

Distressed and angry to have been taken forcibly from their homes and families, they found the climate in Queensland very difficult and had little resistance to diseases such as smallpox, measles, dysentery, pneumonia and tuberculosis. Many could not cope with the different food.

They had to work long hours in harsh conditions, clearing dense tropical scrub to plant sugar cane. They hoed the cane and caught cane grubs. Later they harvested the cane, cutting it down with a sharp knife. For this arduous work, they were paid only £6 a year and were given some clothes and perhaps some accommodation.

Employers were careless about the health and working conditions of South Sea Islander people.

An average of 50 in every 1000 died each year in Queensland. The worst year was 1884, when the death rate for Islander men in the prime of life was 147 per 1000. The comparable rate for European males was 9 or 10 per 1000. The Islanders were most vulnerable when they first arrived in Queensland.

During the later decades, Islander people had a better understanding of life and work in Queensland. Some were eager to come to Queensland in order to be able to take back goods such as axes, clothes and guns to improve their lives and their status in their home community.

Some returned a second or third time to work in Queensland, working under an indenture for 3 years: their employer had to pay them, clothe them, provide medical care and arrange for their return at the end of the contract. Those who re-enlisted for indenture usually fared better than those who were on their first trip to Australia.

Sid Ober of Hervey Bay in Queensland was interviewed in the 1970s about the experiences of his father, Futinaruru, who had first come to Queensland in the 1880s, returning to Aoba, in the New Hebrides (now Vanuatu) at the end of his indenture. After 6 months he came back. He had explained this return to his son:

‘Oh, when you get a bit of Queensland, you sort of get it in your blood. When you see the schooners out at sea in full sail coming in, oh, it gives you the urge. You want to go again. So I came out again.’ Re-enlisting workers often negotiated for better wages – up to £12 a year. Some South Sea Islanders decided to stay on in Queensland at the end of their contracts and these time-expired workers could earn up to £23 a year, which was an improvement, but nothing like the £30 to £50 per annum paid to European labourers.

Some time-expired Islanders worked as fishermen or gardeners. A few bought small landholdings to farm where they could raise a family. Peter Mussing bought a farm of two or three acres (about 1 hectare) near Murwillumbah in New South Wales. His daughter Faith Bandler recalled a happy childhood there.

New and old beliefs and customs

South Sea Islander people could supplement their diet by hunting with bows and arrows. They liked to cook taro and sweet potato in underground stone ovens, but also ate corned beef and damper like many people in Queensland. They carried on traditional religious beliefs such as ancestral shrines as well as adopting Christianity.

Thus the thatched chapel on Farleigh plantation near Mackay resounded with hymn singing every Sunday.

Racial discrimination and intolerance

The sugar industry was built up by the labour of South Sea Islander people, who were renowned for their endurance and hard work. Angus Gibson of Bingera sugar plantation in Bundaberg said, ‘I have seen no one to equal the kanaka in outdoor work’. White people believed they were superior to the Islander people; they called the men ‘boys’ and the women ‘Marys’. Islander children were discouraged from attending state schools. It was only in the 1880s that South Sea Islander people could access hospitals set up for them in Maryborough, Ingham and Mackay.

Other hospitals like Bundaberg Base Hospital created separate ‘kanaka’ wards as European Australians did not believe that they should get medical treatment in the same place as the Islander people.

Driving out those who made the sugar industry

Increasingly, white workers wanted to restrict the jobs and areas in which South Sea Islander people could work. The Islanders were allowed to do only unskilled agricultural work in coastal areas. By 1892, they could not work in sugar mills and later were totally excluded from the sugar industry they had built up. This ban lasted until 1964. Islanders sought to resist these actions by forming organisations and writing petitions.

Indentured South Sea Islanders signed on for three-year work contracts. Many could not read or sign their names, so just a fingerprint was taken. Many thought they were going for only three months and were shocked when they realised they would be away for 39 months. Some marked a tree with every new moon so they would know when they could go home.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 14.3

- Suggest why some South Sea Islander people chose to come back to Queensland.

- Work out what percentage of the highest wage paid to European workers was paid to first-time recruits, re-enlisting workers and time-expired Islanders.

- Find out what you can about Faith Bandler. What has she done to bring the history of the South Sea Islander people into Australian history? (If you wish to find out more about Faith Bandler, read her book, Wacvie.)

Chinese

Chinese traders started visiting the north coast of Australia in 1750s, before European settlement.

On settlement, a few convicts were of Chinese background and others came as indentured labourers, but it was the gold rushes of the 1850s that prompted large numbers of Chinese men to stream into Victoria and New South Wales. Many of these men were from the southern provinces of China around the Pearl River delta and, like other settlers, were seeking to improve their lot in Australia. The Chinese population peaked at around 38 000 in 1880, but later declined. In 1901 there were about 33 000 Chinese people in Australia, less than 1% of the non- Aboriginal population.

European gold miners were critical of the clannish Chinese miners because they weren’t Christian and had unfamiliar ways. Chinese people made up one-sixth of the miners, and some colonists took the view that the Chinese people were too numerous and should not be on the goldfields. In 1855, the Victorian government imposed a poll tax of £10 on all Chinese immigrants arriving in Victoria. In response, Chinese miners started entering Victoria via Robe in South Australia. In 1855–57, 17 500 Chinese people walked 400 kilometres to the goldfields.

Soon South Australia and New South Wales closed the door on Chinese miners.

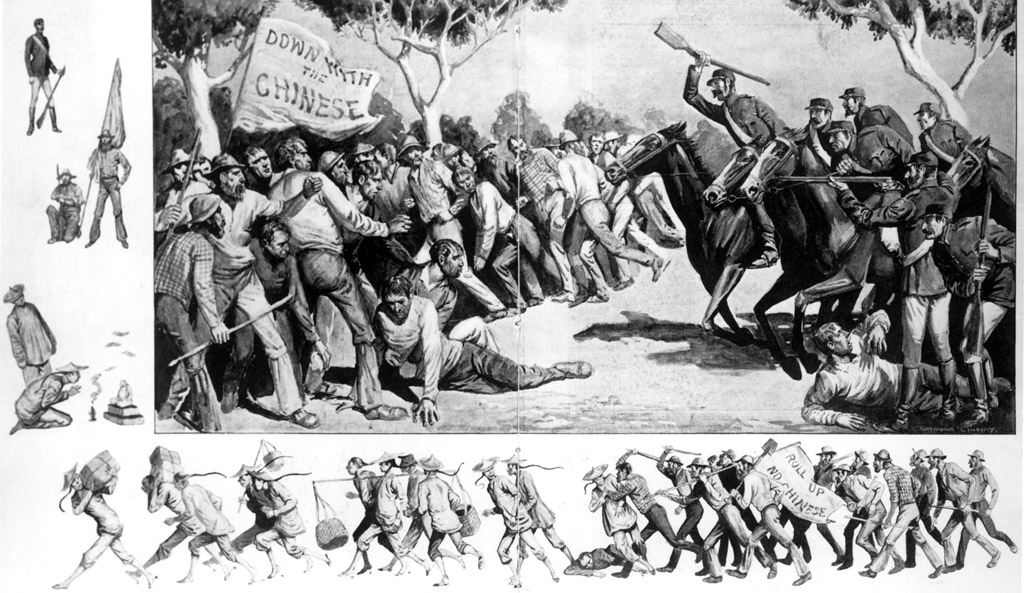

Trouble on the goldfields

As the diggings ran out, some miners wanted to drive out the Chinese people. In January 1861, 1500 miners and traders, some armed with clubs, held an anti-Chinese meeting at Lambing Flat in New South Wales. Most of these were themselves recent arrivals to the colony, but felt justified in attacking Chinese people. The government sent police, soldiers and Special Commissioners to establish peace and to protect the Chinese miners.

The European miners had formed a Miners Protective League, with a catch-cry of freedom – ‘equality, fraternity and glorious liberty’ – but used it to argue for the exclusion of their Chinese fellow miners. Once the military left, tensions rose again and on 30 June, between 2000 and 3000 miners attacked the Chinese camp, burning tents and possessions, hitting and whipping the Chinese and cutting off their pigtails.

As the gold diggings ran out, Chinese people moved into other occupations. In the 1870s around 30 worked at a Rutherglen vineyard, where they were found to be ‘more useful, more economical, and more to be depended upon when in proximity to intoxicants than the Europeans.’ John Chi went from the gold fields to running pearling luggers out of Cossack and Broome in Western Australia. Later he ran a small restaurant in Broome.

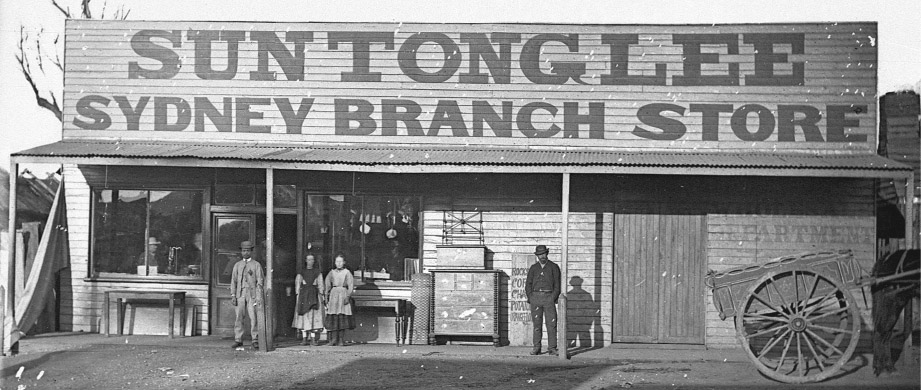

Others made furniture, or ran stores and import and export businesses. Many took up market gardening and supplied towns and outback stations with fresh vegetables. Very often the cook on an outback station was a Chinese man.

Chinese settlers participated in all aspects of life in the colonies. In 1872, the Chinese community around

Beechworth in north-eastern Victoria imported special costumes and banners from China and performed in the Carnival Procession to raise funds for the local hospital and benevolent asylum. Chinese New Year was an important time for celebrations and sharing with European guests. In 1884, at the New Year banquet in the Way Lee & Coy premises in Hindley Street, Adelaide, the European guests enjoyed the Chinese food, but as for chopsticks – ‘How to use these little bits of wood was a puzzle’.

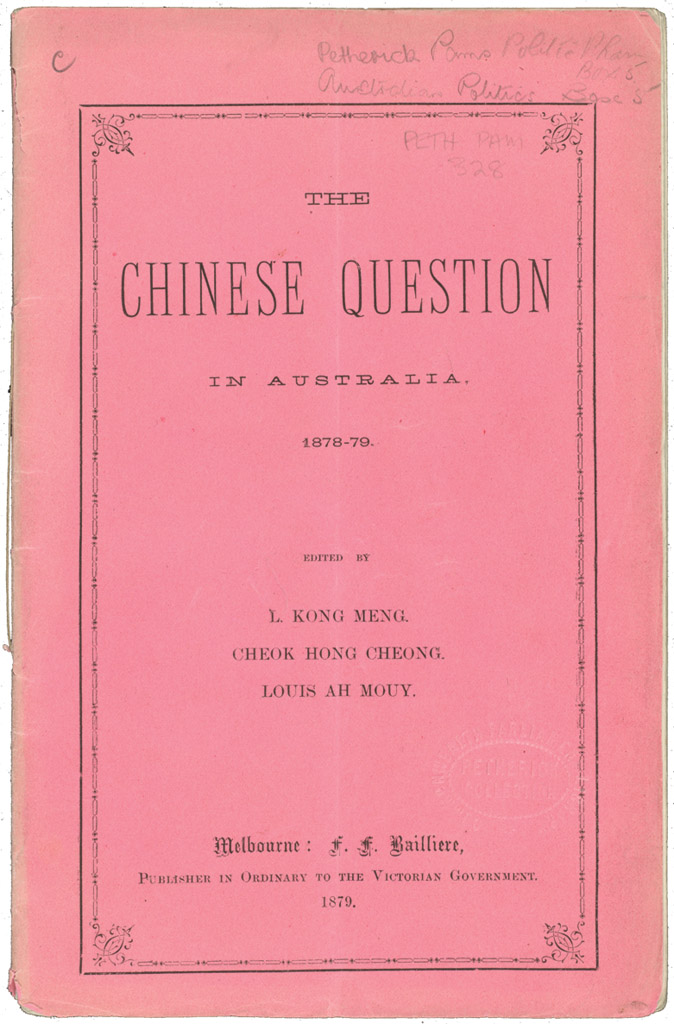

In 1879, three Chinese men wrote The Chinese question in Australia in protest against the laws that discriminated against them. Cheok Hong Cheong had come to Australia when he was 12 years old, gaining his matriculation certificate in Melbourne and becoming a Christian missionary to the Melbourne Chinese. Louis Ah Mouy, born in China and trained in carpentry in Singapore, did well in the gold rushes. He became a successful tea merchant and helped found the Commercial Bank of Australia. The third of these authors, Lowe Kong Meng, like a number of Chinese people in Australia was a British subject, for he was born in Penang in the Malay colonies. Fluent in English, French and Chinese, he was a successful businessman and a shipowner, trading around the Indian Ocean.

These writers pointed out that anti-Chinese legislation was illegal, as it contradicted the 1860 treaty between the Chinese and British governments, which meant that Chinese people had ‘a perfect right to settle in any part of the British Empire’. This treaty also allowed British and Australian people to settle in China.

Reading the Tung Wah Times

The Tung Wah Times began in Sydney in 1898, providing Chinese settlers with useful information about the law and business in Australia, and about life and activities in their home villages in the Pearl River Delta, as well as about the lives of Chinese people living in the United States and other countries. Often they read about the heavy taxes and dictatorial behaviour of the Chinese government. Although they lived in Australia, they were also very interested in developments in their homeland. Many supported moves for reform of the Chinese government and belonged to the Chinese Reform Association. They welcomed the visit of the leading Chinese political reformer, Liang Qichao, who came to Australia in 1900–01 to give talks in many towns and cities about the need to modernise China.

Relatively few Chinese women came to Australia, perhaps because of the hostility to Chinese people that erupted from time to time.

Rose Quong was born in 1879 in Melbourne and had an interesting career. She attended University High School in Melbourne and then worked as a clerk in the public service. But she always wanted to be an actor and later in life worked on the stage in Britain and the United States. She died in New York in 1972.

The late nineteenth century saw more anti-Chinese feeling and more laws to restrict immigration. Australians from European backgrounds came to believe that they were better people and that Australia was theirs.

They argued that their fellow citizens from Asia had no right to live and work in this country.

Quong Tart was nicknamed ‘Quong Tartan’ because he spoke English with a Scottish accent, loved Robert Burns’ poetry and on occasion dressed in Scottish Highland dress.

White workers, such as cabinet makers, waged campaigns to force Chinese people from their occupation. Some furniture made around the end of the nineteenth century bears a stamp, ‘Made by white labour’. In 1888, the colonial governments discussed how they could work to make Australia white and deny Chinese people the opportunity to live and prosper in Australia.

Until recently, Australian historians ignored the history of Chinese people in Australia. Now they realise the importance of Chinese immigrants to the development of Australian society and business. Janis Wilton has researched New South Wales country life and the place of Chinese stores in supplying local communities with food, clothing and a wide range of goods. Historians also now understand how Australian Chinese people took ideas from Australia to change China.

In studying our history we need to investigate Australian relationships with people in the Asia-Pacific region.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 14.4

- Draw a map of the route Chinese people followed from Robe to the Australian goldfields.

- Using the Public Records of Victoria website (www.cambridge.edu.au/hass9weblinks) and other sources, research Chinese work, food and family life in nineteenth-century Australia.

- Research the life of Quong Tart and make a presentation to your class.

Afghans

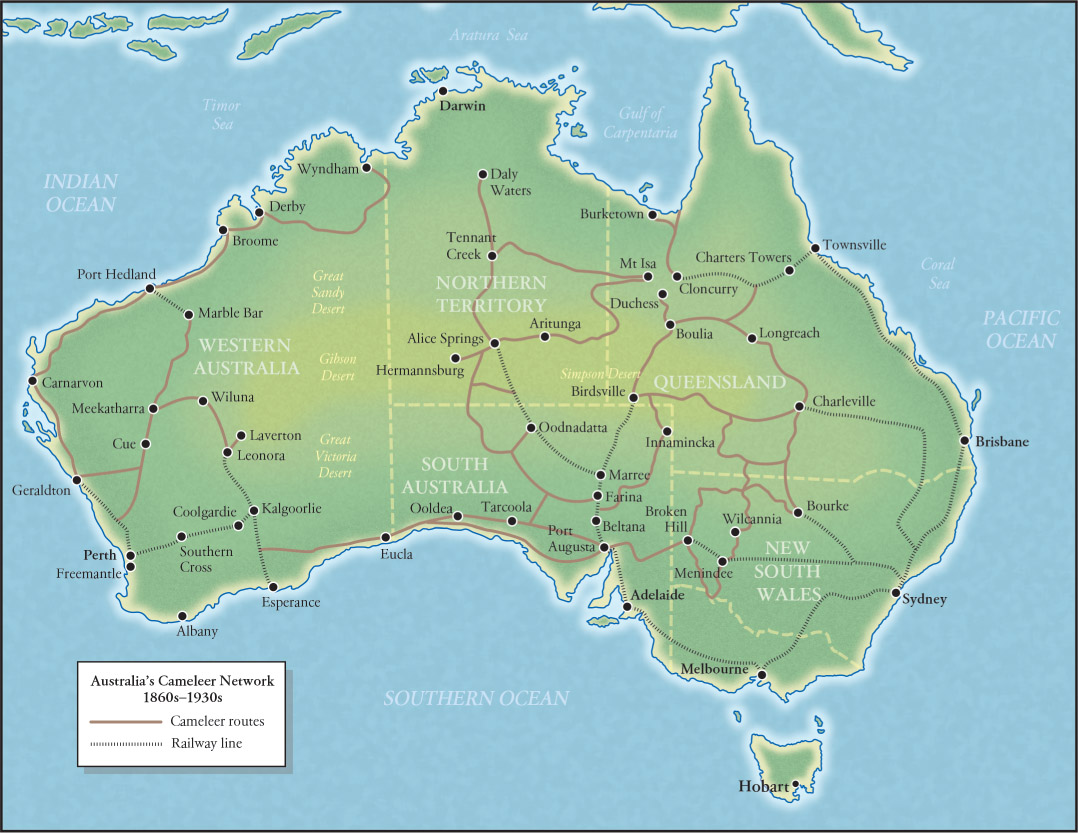

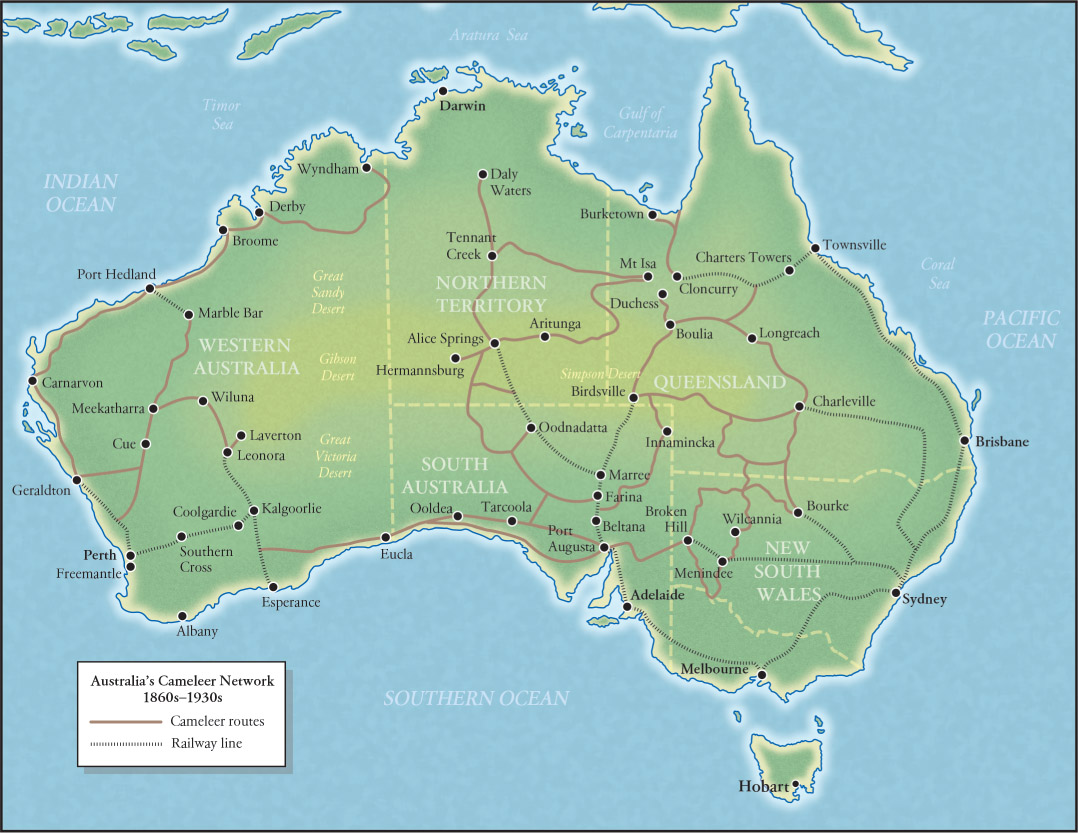

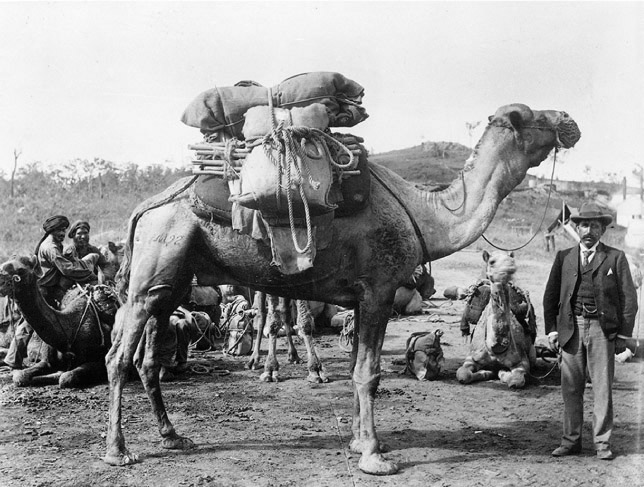

Around 2000 to 3000 cameleers came to Australia from Afghanistan and nearby countries between 1860 and 1920. They first came to handle the camels on the ill-fated Burke and Wills exploration expedition in 1860. This was only one of many exploring expeditions that the cameleers supported. Camels were well suited to travelling the long distances in outback regions while carrying heavy loads. The cameleers contributed greatly to the exploration and the development of central Australia.

At first the Afghan camel drivers worked for Europeans. Later they took over the transportation business across the interior of Australia, through

Queensland and the Northern Territory over to Western Australia. The camel train from Oodnadatta to Alice Springs ended when the train line was extended to Alice Springs in 1929; that train is still called ‘the Ghan’, a shortened version of ‘Afghan camel train’.

In 1865, Thomas Elder, a pastoralist, imported camels with a number of cameleers, including the young brothers Faiz and Tagh Mahomet. In 1888, the brothers formed their own company. Their carrying business did well and by the early 1890s they had 900 camels and employed about 100 of their compatriots across the outback.

Afghan people walked all day with their camels, leading trains of up to 70 camels. Each camel could carry as much as 600 kilograms over long distances with little food or water in all sorts of country. They supplied stations and remote mining settlements, and also supplied the materials for the construction of the 3200 kilometre Overland Telegraph, linking Port Augusta to Darwin, between 1870 and 1872. They carried wool, water, food supplies, timber, mining equipment, furniture and even pianos.

The cameleers also brought Islam to Australia and built mosques in places such as Leonora, Coolgardie, Marree, Adelaide and Perth. While on a trip with their camels, they performed their prayers five times a day out in the desert or the bush. They often worked alone or with a couple of others, but during the fasting month of Ramadan, they would gather together and then celebrate the feast of Eid ul-Fitr.

Afghan people lived in separate areas (known as ‘Ghantowns’) of towns such as Marree, Broken Hill and Oodnadatta. European Australians believed that they were superior to the Afghans and looked down on them. Many of these men were single or had left a wife and family back in Afghanistan, visiting them only occasionally.

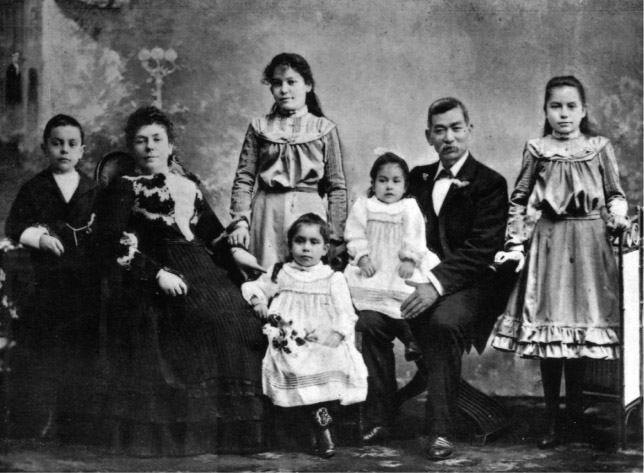

Some had families with Aboriginal women and some Aboriginal families still have surnames like Khan, Abdulla and Dadleh. Others, like Abdul Wade, married women of European backgrounds.

He and Emily Ozadelle married in 1895 and had three sons and four daughters.

In the late nineteenth century, anti-Afghan prejudice grew and some Europeans wished to drive Afghan people from Broken Hill or the West Australian goldfields, where recent migrants claimed Australia should be for the white man.

Government policies were discriminatory. In 1896, Faiz Mahomet, a successful merchant who had lived for 22 years in Australia, was shocked to find his application for naturalisation was denied by the West Australian government.

Late in the 1890s some colonies passed acts restricting the immigration of people from Asia and this meant the Afghan people found it hard to travel to Australia.

-

Source 14.15 Abdul Wade came to Australia from Kabul in 1879. In 1892 he imported 340 camels and brought 59 camel drivers to work them. His Bourke Carrying Company in western New South Wales allowed him to become wealthy and return to Kabul to retire. He was one of the prosperous camel entrepreneurs who financed the building of the Adelaide Mosque, now the oldest mosque in Australia, in the 1890s. -

Source 14.16 Adelaide Moosha and her children Nazhebe, Zainabi, Lal and Partimah in Marree, 1910. Her husband, Moosha Balooch, was a cameleer.

-

Historical thought

The descendants of the Afghani camels number around 1 million and run wild in central Australia. Today, Australia exports camels to Saudi Arabia.

Japanese

Japanese people were not permitted to go abroad until 1866, so few came to Australia during the nineteenth century. By the 1870s, small numbers had arrived, often from fishing villages on the southern coast of Japan. Most went to pearling centres such as Thursday Island off the tip of Cape York Peninsula, and Broome in northern Western Australia. By 1901, around 3400 Japanese people were in Australia and only 400 of them were women; 90% lived in northern Australia.

Japanese divers were very important to the development of the pearling industry, which sold large amounts of pearl shell to international markets to make buttons. In the first decades of the twentieth century, Broome produced 80% of the world’s mother-of-pearl shells. Japanese people were expert divers, using the helmets and diving suits developed from the 1880s. Some came as indentured workers and had to pay back their fares before they could keep their own wages.

They braved the dangers of pearling, getting the bends, and facing sharks and cyclones. In Broome’s Japanese cemetery are the graves of hundreds of Japanese men who died seeking pearls.

In 1896, the Japanese government set up a consulate office in Townsville, Queensland to serve the many Japanese citizens in the area. As the Queensland and, later, the Australian governments passed restrictive immigration legislation, the consul protested on behalf of his government.

Japan as an independent government rejected the humiliating and racist treatment of Australian governments towards its people.