14.1 Extension of settlement and contact

Spread of convict settlement

White settlement in many parts of Australia began with a combination of convict labour and military supervision. Convicts and soldiers were the first inhabitants to arrive and lay the bases for British civil society in every Australian colony (except for Western Australia, where convicts arrived later, and South Australia, which received no convicts), as well as the Northern Territory. Military officers also planned every capital city except for Darwin.

Sydney, Hobart, Brisbane and Melbourne began with small convict settlements. Sydney was the centre of the convict system from 1788 until the Hyde Park Convict Barracks closed in 1848.

Around 80 000 transported men and women were sent there. Hobart continued receiving convicts until 1853. Brisbane was originally the site of the Moreton Bay convict settlement, which was the harshest mainland centre for repeat offenders between 1824 and 1842. Melbourne, which is rarely thought of as having convict origins, was actually preceded by several attempts to form a penal station: near Sorrento in 1802; at Westernport Bay in 1826–27; and then from 1837 in the Melbourne region itself. Later, between 1844 and 1849, a further 2500 ex-prisoners (called ‘exiles’) were sent directly from Britain to Port Phillip.

Although Perth was founded by free migration from 1829, economic failure led to the introduction of convicts between 1850 and 1868. As a result, such important structures as Government House, the Town Hall and Perth Boys School were built by supervised convict labour.

Australia’s early road system in many regions was constructed by iron gangs of convict workers.

By 1829, convicts had completed 150 miles of the road south from Sydney, 120 miles of the road west to Bathurst and a connecting road north to Newcastle. Between 1850 and 1862, Western Australian convicts cleared, laid, drained and repaired hundreds of miles of roadway; built around 240 bridges and several public buildings; sank wells; and constructed fences, jetties, tramways and a sea wall. Additionally, convict workers, supplied to private employers across New South Wales and Tasmania, pioneered the earliest pastoral and agricultural industries.

Statistical work has now shown that convict workers possessed many skills essential for the task of nation-building. They were really a cross-section of the British and Irish working class and had similar levels of industrial capacity and literacy. They represented more than 1000 different occupations; however, many were trained as tailors, tanners, blacksmiths, bakers and boot-makers, which made them more suited to city life than a rural existence as shepherds and farm labourers. Around 4000 of the convicts were from non-British origins and 1000 or so of them were non-white, sent from regions all over the British Empire.

Around half of the 24 700 females transported were originally domestic servants. In such centres as Hobart, George Town, Launceston and Ross (Tasmania); Newcastle, Port Macquarie, Parramatta and Bathurst (New South Wales); and Brisbane Town and Eagle Farm (in what became Queensland), they were confined in institutions called ‘female factories’. Several of these became Australia’s first manufacturing centres; for example, in 1843 the Cascades Female Factory near Hobart employed 700 women for textile and blanket weaving, needlework and laundry.

Historically, embarrassment over the nation’s penal origins has hidden the convicts’ important foundational role in establishing British settlement in Australia. Modern research is rectifying this.

The last transported convicts in Australia were six men pardoned in 1906 by Prime Minister Alfred Deakin. The longest surviving ex-convict was Samuel Speed, who died at the age of 95 in 1939, on the brink of World War II.

White settlers and Indigenous occupants: first contacts

Contact between Europeans and Indigenous Australians has been occurring for a surprisingly long time. The first recorded meetings took place more than 400 years ago in 1606, when Dutch mariner Willem Jantz and his small crew encountered members of the Wik people on western Cape York. Several months later, Breton sailor Luis Baez de Torres and his Spanish crew contacted Torres Strait Islander people further to the north. Both meetings were violent ones: the Wik remember the Dutch appearing like ‘devils’ on ‘a big mob of logs’ and shooting their people – some of the Dutch were speared in turn – while de Torres’ men began kidnapping the Torres Strait Islander people.

The first known British contact was made with the Badi people in 1699 by English pirate William Dampier at Lagrange Bay on the northwest coast of Western Australia. Dampier is on record as calling the Aborigines ‘the miserablest people in the world’. It now seems that Dampier did not write these words. His publisher probably inserted them to spice up Dampier’s book for its British audience.

The reactions of white explorers and colonists to Indigenous people, however, were often negative. Britons and Europeans regarded their own cultural and technological achievements – and thus themselves – very highly. They saw a lack of material possessions among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as evidence of inferiority. Furthermore, as the British were intent on seizing their lands, it was not in their interests to give a good account of their Indigenous hosts.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, in turn, often took the sudden arrival of these strange white beings as evidence of a spiritual visitation. They saw the whites as ‘ghosts’ or reincarnated ancestors. The potential for cultural misunderstanding was therefore both strong and mutual, and often led to unforeseen or tragic outcomes.

Many of the early encounters took place at penal stations. In such circumstances, the new arrivals were substantially outnumbered by the Indigenous people surrounding them. They often felt their vulnerability intensely. Aboriginal people recoiled from the spectacle of public floggings and executions, which they saw as primitive and barbaric. They also wondered why so many of these spirits had come among them and how long they intended to stay. Concerns and apprehension grew as the newcomers’ presence put increasing stress on the available natural resources.

First encounters led on to more complex relations that fluctuated between conflict and conciliation. At Sydney Cove in 1788, Cadigal and Gayimai people danced for and with male and female convicts and Royal Marines. Where language difficulties hampered communication, body language, expressed as dance, helped to improve it. On the other hand, sailors travelling with French explorer La Perouse, after building a fortification at Botany Bay, opened fire on the Eora in late February 1788. Convicts, in turn, were attacked by the Eora in early March. And so the saga of interracial colonial violence began with spearings and shootings, kidnappings and reprisal raids, as initial friendly relations eroded.

By April 1789, a devastating epidemic of what was probably smallpox had broken out among the Eora,

The Bedaigal and Gweagal people of Botany Bay called the First Fleet arrivals Berriwangal (‘People of the Clouds’).

who had no immunity to exotic diseases. Around 2000 Aboriginal people perished horribly, making this the most dramatic event in early Australian contact history. The origin of this outbreak has never been satisfactorily explained.

Free settlement

Alongside convict transportation between 1788 and 1868, an increasing number of free settlers arrived. They were mostly English, Scottish, Irish and Welsh, but also included smaller minorities of Europeans (especially Germans and Scandinavians). They had voluntarily decided to sail to the Australian colonies hoping to improve their lifestyles and material circumstances. It was an adventurous move, involving one of the longest sea voyages in the world, taking between 3 and 5 months to complete. Crowded shipboard conditions varied from tolerable to terrible, making the journey a lottery in terms of comfort and survival. No one quite knew what to expect at the end of it.

By the 1820s, only around 1000 free migrants had arrived. Though small in number, they were large in impact for they were wealthy people who were given land grants and batches of convict labourers to work their new estates free of cost. The more money they had, the more land and convicts they were given by the colonial government. These gentlemen settlers were usually agricultural entrepreneurs who developed farms and the first sheep stations around Sydney and across Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania), sometimes even bringing their own workforces; during the 1840s these included bonded workers from India, Melanesia and China.

From 1831, however, land auctions took the place of grants. The money raised was used to assist the migration of poorer workers who could not afford their own passages. The new scheme was called ‘systematic colonisation’. Under its regulations, 1.75 million acres of land were sold, helping to introduce 100 000 migrant workers by 1850, creating a colonial working class.

Most of the migrants came from the rural areas of southern England, the Irish countryside and the Scottish highlands. Convicts, by comparison, were often from large urban areas, such as London and Lancashire. By the 1850s, more than half the Australian population had been born in Britain.

It was planned to introduce migrants in roughly the same ethnic proportions as they existed in Britain, but this proved difficult to accomplish. More Irish (28%) migrated than was intended, and fewer Welsh (under 2%). The English predominated at around 55%, while 15% were Scots. The higher Irish proportion led to strong religious tensions between Catholics and Protestants that persisted well into the twentieth century.

South Australia was the only colony begun entirely by free migration. It was planned by the same man who organised the ‘systematic colonisation’ scheme, Edward Gibbon Wakefield.

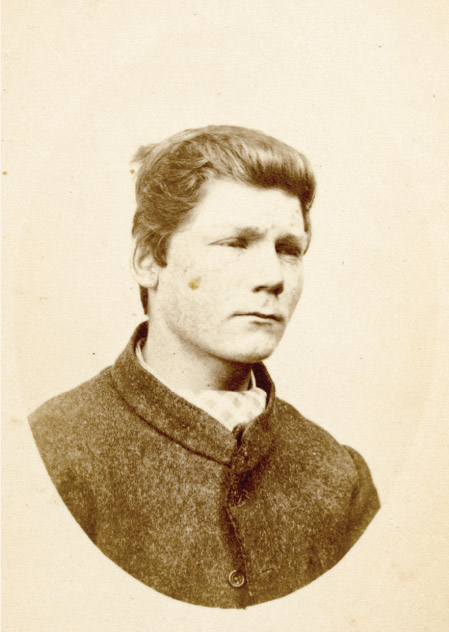

Wakefield had served time in prison for abducting a 15-year-old female heir, so he knew something about what it meant to be a convict. But he was more concerned that the sale and distribution of what he referred to as ‘wasteland of the Crown’ (conveniently ignoring Aboriginal ownership) be used to produce a new kind of social order, with nicely graded divisions of wage labourers, middle-class townspeople and prosperous landowners.

Land in South Australia was controlled by a Board of Commissions rather than the Governor (as in New South Wales) and it sold for around 250% of its price in Sydney. By December 1836, the new colony was proclaimed with high hopes that it would not follow the same haphazard path as the Swan River settlement in Western Australia.

Yet its early migrants were also discouraged by the searing heat and parched lands that were so different from their cool and green countryside in Britain.

The cost of a steerage passage to Australia during the 1840s was eight times higher than one to Canada or the United States.

Wool and gold

Prosperity in the Australian colonies was largely due to the production of fine merino wool for the clothing mills of England and the discovery of gold.

Next in economic importance were beef and sugar. Gold rushes could produce sudden, soaring successes, but could then peter out until the next big find. Taken together, the products of pastoralism – wool, meat, hides and tallow – were a more dependable, ongoing financial prospect.

The pastoral industry’s origins are both epic and controversial: on the one hand are vast, overland treks of cattle and sheep, great sagas of endurance, and memorable struggles against drought, flood and fire. On the other, however, are less admirable struggles against imperial and colonial law, a monopoly over huge parcels of land and extended conflicts with Indigenous people.

The pastoral industry was established by the early 1800s, after former soldier John Macarthur separated merino sheep from the rest of his flock to produce a superior wool clip. Macarthur was granted an estate of more than 4000 hectares where he and his wife, Elizabeth, extended their experiments. By the early 1830s, others were moving beyond ‘the Limits of Location’ in New South Wales (that is, the 20 counties of authorised white settlement around Sydney) and illegally occupying Crown land. Some were ex-convicts, but all were called ‘squatters’ – a word used in the West Indies to describe former slaves ‘squatting’ without permission on marginal lands. Wealthier landlords followed them, often seizing hundreds of square kilometres of territory. But the name ‘squatter’ stuck.

Throughout the following decades, squatters played an extended cat-and-mouse game with officials from Gippsland to the Darling Downs, attempting to evade licence fees and a growing amount of regulation. They regarded attempts to make them pay more than nominal rents for their enormous landholdings as ‘a nuisance that should not be endured’. By 1844, they were even threatening armed resistance. Governments argued they were in ‘systematic violation of the law’, while city-based movements to ‘unlock the land’ from the squatters’ grasp so that small farming could advance, demanded impatiently: ‘Should Australia be a sheep-walk forever?’ But the pastoralists’ powerful worldview usually prevailed.

When a gold rush began at Ophir, near Orange and then at Sofola on the Turon River in New South Wales in mid-1851, it started a colonial frenzy that would ensure an end to convict transportation. Exile to a gold rush hardly seemed a punishment! Populations exploded across Victoria, New South Wales and, eventually, Queensland and Western Australia. Great wealth was generated among the fortunate; democratic principles were advanced and social change was accelerated. Social disorder also increased as settled class relations were upended.

Gold discoveries at Ballarat, Mount Alexander and Bendigo Creek expanded Victoria’s population fourfold in 3 years. The rush would help create ‘Marvellous Melbourne’, one of the great cities of the British Empire. But it also created social and political turmoil.

Miners paid high fees for their tiny claims in comparison with the squatters’ low rents for their enormous holdings. Miners had no votes and pastoralists often had several. Resentment grew. Heavy-handed policing of miners evading payment led to disturbances and uprisings, the largest and most important of which was at the Eureka field near Ballarat in 1854. The outcome was a military victory for the Crown but a moral one for the miners. Republican sentiments were expressed and a new flag – the Southern Cross – was flown. Around 34 miners were killed and wounded by soldiers and police, but Melbourne jurors refused to convict 13 ringleaders for treason.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 14.1

- Recount how the wool industry developed in the Australian colonies.

- Explain why pastoralists were called ‘squatters’.

- Determine why pastoralists’ early land-taking activities were considered illegal.

- Assess why pastoralists resisted official control.

- Research when the gold rushes began. Was this the first gold discovered in Australia?

- Describe how the gold rushes led to democratic reform.

- Analyse how socially disruptive the gold rushes were.

White settlers and Indigenous occupants: the moving frontier

Among white settler colonies, Australia was unique in failing originally to recognise any form of Indigenous land rights or to have entered into any treaty obligations with the original inhabitants since that time. This decision was based upon three legal fictions. First, in terms of property rights, land was judged to be unoccupied (that is, res nullius or terra nullius) and thus simply there for the taking by the British Crown. Second, it was decided that Indigenous people were not members of distinct and separate societies that were being trespassed on, but rather were part of the arriving society itself: that is, theoretically they were British subjects. This meant that any resistance they offered to their dispossession was not viewed as a legitimate defence of territory, but rather as a criminal act of disorder and rebellion. Further, most citizens’ rights – such as the right to seek legal redress, give evidence or defend oneself in court – were initially withheld.

These two positions led logically to the third: that the territory of Australia had not been invaded and conquered by the British incomers, but rather settled in a relatively peaceful and orderly fashion. Settlers’ struggles were predominantly seen as being with the land itself – with fire, flood, drought or insect plagues – rather than with its human inhabitants. This interpretation of events had become commonplace by the early twentieth century.

The real situation, however, was very different from these legal constructions. Around 500 to 600 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ‘First Nations’ – spread across the entire Australian mainland, within the Torres Strait and in Tasmania – had been in full possession of the landmass for probably 50 millennia or more. They had a strong sense of their territorial sovereignty and were quite prepared, in most instances, to defend this with force. They had left their mark on the landscape in multiple ways. Most significantly, they had created the lush grasslands so attractive to white pastoralists with their flocks and herds by a continual process of fire-stick farming. The land was far from an uninhabited one: there were probably around 750 000 inhabitants when the first 1080 Britons arrived.

So the British arrivals were not simply transposing themselves across the globe into an open and waiting land. They were actually imposing themselves upon long-established and well-functioning social orders of hunter-gatherer people. They were taking everything, conceding nothing and behaving very differently from new migrants arriving in Australia today.

The first penal stations were relatively small and stationary. Yet the huge pastoral advances and the large population influxes that came with the mineral rushes, along with all the inroads made by farmers, timber-getters, fishermen and townspeople, transformed everything. The frontiers of contact became rapidly moving, land-hungry and highly contested zones. In most regions, there were numerous incidents of frontier violence and massacres, resulting in heavy casualties on both sides.

These difficult origins have become a highly controversial aspect of modern historical research. It is hard to arrive at an accurate figure of the number of British, European, Asian and Melanesian incomers who were killed and wounded in the struggle. It is even harder to determine the considerably higher Aboriginal casualty rate. Attacks, ambushes, clashes and massacres of Aboriginal people were sometimes concealed and the actual numbers killed each time rarely recorded. Scenes of individual or group murders of Aboriginal people were only occasionally treated as crime scenes, and the law itself was slow to intervene on their behalf.

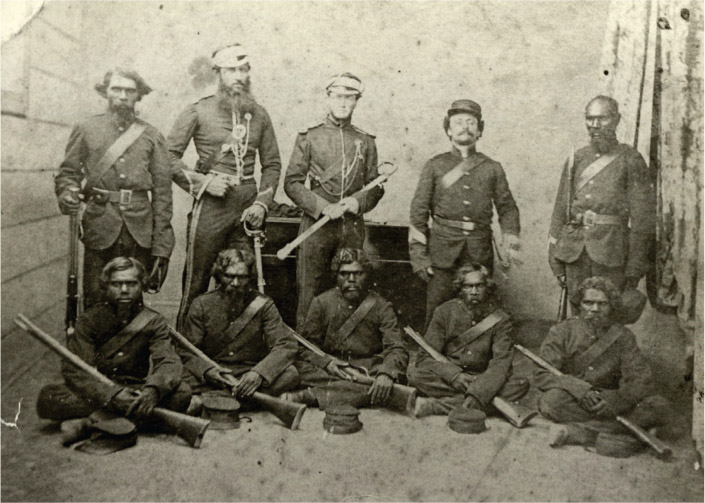

Along with private bands of settlers, often police and military-style forces were themselves directly involved in destroying Aboriginal communities.

So our detailed understanding of events is often clouded by lack of precise documentation.

Available records, however, convey a strong impression of widespread destruction, lasting from the 1780s to the 1930s across most Australian regions. Land dispossession was the central act of violence in this process and from it all the devastating effects of imposed disease and mayhem flowed: epidemics and aggression, the taking of Indigenous children, sexual and labour exploitation of Indigenous women, labour exploitation of Indigenous men, the destruction of Indigenous cultures and languages, and the general disintegration of Indigenous societies. It is one of Australia’s largest stories and one of its most tragic.

Squads of young Aboriginal men were taken from other regions, armed with rifles, mounted on horseback and placed under white military discipline. Called Native Police, they were used against other Aboriginal societies by colonial governments in Victoria, New South Wales, Queensland and South Australia.

RESEARCH 14.1

Prepare an account of frontier relations in one of the following regions:

- Adelaide hinterland

- Cape York Peninsula

- Cardwell district

- Central Tasmania

- Gippsland region

- Gulf of Carpentaria

- Hawkesbury River district

- Kimberley district

- New England region

- Roper River region

- South-western Australia

- The Darling Downs

- Torres Strait.

You can also select your own region of Australia for analysis. Present your account to the class orally.

Australia approaches nationhood: the 1890s

The 1890s was one of Australia’s most difficult decades. It began with enormous strikes in the shipping, mining and pastoral industries from 1890 to 1896. These were accompanied by a serious economic depression, beginning in early 1892 and continuing, with little relief, into the new century.

During the 1880s, the Australian colonies had been a leading field of British investment.

Australians, per head of population, were more heavily in debt to Britain than anywhere else in the world. By the 1890s, there was a massive withdrawal of British funds to the gold and diamond mines of the Transvaal in South Africa, bringing the local economy to its knees. The building industry, most land companies and many of the major banks collapsed. This slump was deepened later in the decade by what became known as ‘the Great Federation Drought’, lasting from 1898 until 1904–05.

Over this 15-year period, migration and overseas investment almost ceased. There was massive unemployment as the economy shrank by one-third. In the countryside, great privation existed. Sheep and cattle numbers fell by more than half. To make matters worse, two thoughtlessly introduced species, rabbits and prickly pear cactus, were ravaging the bush. Rabbits had spread from Victoria across New South Wales and into Queensland and Western Australia. Dust storms followed in their wake. By World War I, the prickly pear had overrun 9 million hectares of Queensland and New South Wales.

The one bright spot was the success of the Australian mining industry. The 1890s was its best decade to date. Australia became the world’s largest producer of gold, and mineral exports outstripped wool. The Western Australian gold belt around Coolgardie-Kalgoorlie, sourced in mid-1893, was largely responsible for this success, but other centres – such as Charters Towers in Queensland, Broken Hill in New South Wales, and Ballarat and Bendigo in Victoria – remained in full production and helped to create some of Australia’s largest inland towns.

By Federation in 1901, there were 3 773 801 non-Aboriginal Australians. Most had now been born in Australia (though of British origin) and were spread thinly over a vast landmass, roughly the same size as the United States. Although they liked to picture themselves romantically as ‘bushmen’, Australians by the 1890s actually formed the most urbanised society on earth, mostly clustering near the coastline in six capital cities.

Census figures give only a rough estimation of the number of surviving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people at this time, which was somewhere in the range of 67 000 to 90 000. This indicates a devastating population fall from an estimated 750 000 at first contact in 1788. White Australians concluded that such numbers were in irreversible decline, and Aboriginal people were cast as ‘a dying race’. Few observers, however, wished to take any responsibility for this. Instead, it was argued by both scientist and average citizen that the decline was simply ‘a fact of nature’ about which little could be done. ‘Inferior races’, it was thought, must ‘fade away’ in the face of the impact of the ‘superior’ British racial type. Aboriginal people became wards of the state, often secluded on reserves and mission stations, and stripped of most citizen rights and public dignity.

Queensland from 1897 provided the model for the harsh systems of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander control that were later established in Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory, where most of the surviving Aboriginal people lived.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 14.2

- Compare why pastoralism was doing so badly and mining was doing so well in the 1890s.

- Discuss why there was so much working class discontent.

- Identify why rabbits and prickly pear were introduced into the colonies.

- Explain why Australians liked to think of themselves as bushmen when they mostly lived in cities.

- Assess why the rate of Aboriginal population decline was so dramatic.

- Examine why a racial ‘solution’ of segregated Aboriginal reserves and missions was adopted.