13.2c Role of progressive ideas in major social upheavals: Rights

Anti-racism, anti-colonialism and non-violence

In the second half of the nineteenth century, the notion that some races were more ‘evolved’ than others was widely accepted. This belief enabled people to tolerate systems of injustice based not only on social class but also on the idea of the ‘superior’ white race ruling the ‘inferior’ non-white populations. These beliefs underpinned the actions of colonialism, allowing the colonising country the comforting thought that they were ‘helping’ the less developed nations.

In the space of 18 months, two men were born on opposite sides of the globe who would become famous throughout the world for their struggles to end discrimination against non-white people and to challenge the ideas of colonialists. Those men were Mohandas Gandhi, born in India, and William Edward Burghardt (W.E.B.) Du Bois, born in the United States.

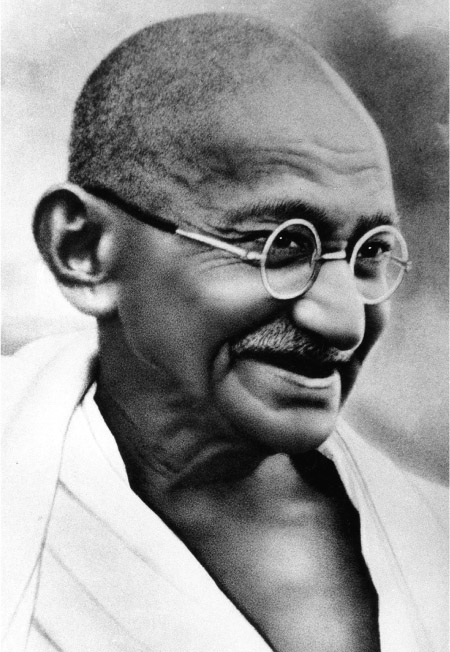

Mohandas Gandhi (1869–1948)

Gandhi, often referred to as Mahatma (Great Soul), was born in India, near Bombay (known today as Mumbai), to well-to-do parents who ensured he had a good education. They wished him to become a barrister and sent him to London to train in the law. Gandhi returned to India as a qualified barrister, but in 1893 he accepted a post in a law firm in Natal, South Africa. At that time both India and South Africa were under British colonial rule as part of the vast British Empire. As a young man Gandhi had absorbed many of the beliefs of his Hindu and Jain forbears. He was a vegetarian, he practised compassion towards all sentient beings and he believed in tolerance between people of different faiths. He often fasted in order to attain self-purification.

In South Africa, Gandhi was shocked at the treatment of the Indian population there and suffered considerable discrimination himself.

His experience of racism and prejudice led to his lifelong activism in South Africa and India.

He is revered for his dedication to non-violent protests and to civil disobedience, rather than violent action, to achieve political goals. Gandhi spent several years in South Africa, founding the Natal Indian Congress in 1894 and uniting South Africa’s Indian population. On his return to India in 1915, Gandhi became a central figure in the struggle for Indian independence from British rule. He perfected the art of non-cooperation with unjust laws and developed a huge following. His influence was a vital factor in India’s achievement of independence in 1949.

W.E.B. Du Bois (1868–1963)

W.E.B. Du Bois was another man who devoted his life to fighting inequality among races. Born in Massachusetts, Du Bois came from a mixed race family with African, French and Dutch forebears.

Du Bois was an African-American scholar, educator and activist. He was well educated, gaining degrees in Nashville, Tennessee, then at Harvard University. He was the first African-American to gain a Harvard doctorate and his thesis on the history of the slave trade is still considered one of the most detailed on the subject. Du Bois became a university teacher at Atlanta University and throughout his long career wrote many influential books and articles about African-Americans and their place in US society. He was a great supporter of black nationalism and of civil rights for African-Americans. Du Bois became the head of an organisation called the National Association for Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

His work provided much of the thinking that underpinned the civil rights movement in the United States in the 1950s and 1960s.

Interactive 13.1

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 13.8

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 13.9

Gandhi’s theories of non-violence and anti-racism have inspired countless people from former South African President Nelson Mandela to US President Barack Obama, civil rights activist Dr Martin Luther King, Burmese political leader Aung San Suu Kyi and even Beatles band member John Lennon. Hold a class debate arguing whether ‘non-violence is more effective in achieving independence than violence’.

Egalitarianism: a key progressive idea

Now that we have examined a wide range of influential thinkers stretching from the period of the Enlightenment to the late nineteenth century, let us return to one idea in more detail: egalitarianism. This idea was a key driver of the American and French revolutions, as well as a slave uprising in Haiti. One of the features of the last decade of the eighteenth century (the 1790s) was the strong radical impulse fuelled by both Enlightenment ideas and the revolutionary fervour of the times. Much of that radicalism focused on the equality and liberty of the individual.

As we have seen, the Industrial Revolution gave rise to major economic and technological changes and to the rapid growth of capitalism.

Vast inequalities of wealth led concerned people to argue that such gaps between people’s lives could not be justified. Some should not be rich while others endured grinding poverty. Nor could a form of government be justified that only allowed certain rich or noble white men to have a say in making laws for all citizens. Working men and women read the works of Tom Paine and others and joined associations such as the Chartists, hoping to bring about peaceful change by parliamentary means. While the Chartists sought more parliamentary representation for men, many women also argued that they also should have the vote. Some read the works of writers such as Mary Wollstonecraft and Marie Olympe de Gouges. Non-white populations and colonised people began to question their place and to assert their rights.

Significant activists began anti-racist movements.

Monarchy was increasingly questioned, although the constitutional monarchy of Britain was seen as more representative than the French monarchy.

Privilege by birth or ability?

Overall, the idea that birth status would determine one’s future life pattern was challenged. Should the son or daughter of a rich family always be rich while the children of paupers were destined for poverty? Would black people always be considered inferior? Many Christians sang the hymn ‘All things bright and beautiful’, which contains the verse in Source 13.15.

The rich man in his castle,

The poor man at his gate

He made them, high or lowly

And ordered their estate.

Source 13.15 An excerpt from All Things Bright and Beautiful by Cecil F Alexander (1848)

This seemed to imply that one’s position in life was God-given and could not be changed – that God ‘ordered their estate’, high or low. Yet many felt that education could change that ordering.

They disputed the notion that only certain rich people could hold high office, or be guaranteed certain careers. The radical idea that a career could be based on ability or merit, rather than birth or skin colour – which we now take for granted – took root. Many people worked hard to educate themselves and their children so that they could compete for better jobs and raise themselves from poverty. Education was a critical element in bringing about this change.

Education – a progressive idea?

Before the Enlightenment, the church controlled education and what was taught. One of the outcomes of Enlightenment thinking was that religious and general education were separated.

Modern subjects as well as the classics (Latin and Greek) were introduced. The influential Swiss thinker, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, for example, advocated radical new approaches such as ‘natural education’ for children and the creation of a unified national system of education. Such a national system was actually put into place in Poland in the late 1700s. Both of these developments we take for granted now.

Writers who advocated equality for all, such as Thomas Paine and Mary Wollstonecraft, saw education as a vital plank in preparing all individuals as citizens of their society. At New Lanark, Robert Owen provided schools for children and evening classes for adults. By the end of the nineteenth century, most Western countries provided compulsory elementary (primary) schooling for children, although attendance was often sporadic and children could be excused from classes to help families at busy times.

In Australia, as elsewhere, a national schooling system was established in the 1870s and 1880s that aimed to give all children a level of elementary schooling (eventually, after World War II, there was increased access to secondary schools). In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, a very small percentage went on to universities after completing their school certificate. Throughout the twentieth century, the age of leaving school was gradually raised.

Further, an increasing proportion of successful school finishers went on to university, so that today about 26% of the population has a university degree. In the group aged 20–24 years in early twenty-first-century Australia, more women than men were studying for a university degree. In theory, all girls and boys, no matter what their background, can now experience an equal and professions. This is the fulfillment of the egalitarian education and be equally prepared for a range of jobs dream for education.

RESEARCH 13.2

Using the library or the internet, investigate Rousseau’s idea of natural education.

- What are some of its features?

- Do we draw on any of Rousseau’s educational ideas today?

- Did Rousseau’s educational ideas apply equally to boys and girls?

- Do all girls and boys in contemporary Australia share absolutely equal educational opportunities? (Consider factors such as different types of schools, where people live, different family circumstances and Indigenous versus non-Indigenous students.)

- Why might education be considered a progressive idea?

Slavery and the rights of Indigenous people

The struggle to abolish slavery was another legacy of Enlightenment thinking. If everyone was created free and equal, how could slavery be condoned?

In 1833, after a lengthy battle, Britain abolished slavery in most of its empire, freeing 800 000 slaves. The movement to abolish slavery was led by a group of devout English Christians whose consciences led them to seek social justice. They formed networks with politicians and journalists to further their cause.

This group was also concerned that indigenous people in the new colonies were not being treated fairly. They were particularly troubled about the way Aboriginal people had been mistreated in the Australian colonies of Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania), New South Wales and Western Australia. Thus they insisted that in drawing up the 1836 Letters Patent (the founding documents) for the settlement of South Australia, Aboriginal people’s ‘incontrovertible right to their own soil’ (that is, their property rights) should be acknowledged. Sadly this did not occur. Until the famous Mabo judgement of 1992, Aboriginal land ownership, or ‘native title’, was unacknowledged throughout Australia, although some states and territories (specifically the Northern Territory and South Australia) had passed Land Rights legislation.

In the United States, slavery was abolished in 1865 after a bitter war between the southern and northern states of the union. The movement to free slaves was one of the most successful progressive campaigns in history, achieving its goal in a relatively short time. The struggle for Indigenous people to win property rights, however, is an ongoing and difficult battle.

The women’s movement and the struggle for equal rights

Another of the key claims of egalitarianism was for equality between men and women. As outlined earlier, women such as Mary Wollstonecraft and Marie Olympe de Gouges were writing on this topic from the 1790s. There were others before them, but there was a long struggle before the idea of equal rights for men and women gained acceptance to the degree that has been achieved now. In this section we discuss some of that struggle, then consider the impact of the campaign for women’s rights – or feminism – in Australia.

Some of the progressive movements covered in this chapter included the equality of men and women in their claims. During the French Revolution, demands were made for women’s rights as citizens. In early-nineteenth-century England, followers of Robert Owen, known as Owenites, made equality of the sexes a central aim of the transformed society they sought. Chartists, while not as radical as the Owenites, numbered many women among their members. Initially they included women’s right to vote in their demands, but later dropped that issue as they felt it would impede progress towards gaining all men’s right to vote.

Much more radical were the British Owenites (1820s to 1845). They were socialists who had some decidedly controversial views on relations between women and men. Owenites believed in a new world where all classes and both sexes would be equal. They claimed to be producing a New Science of Society. Compare their ideals of ‘cooperative communitarianism’ with Australian society today:

- communal living – eating, working, socialising to be undertaken communally

- the abolition of private housework

- childcare and education to be the collective responsibility of the community

- civil marriage

- accessible divorce

- birth control

- support for women’s political involvement

- the right of women to speak in public

- cooperative organisation of work.

The Owenite movement did not survive after the 1840s, although a thread of their ideas persisted throughout the nineteenth century. It was a predominantly working-class socialist movement; one that envisaged the end of capitalism and the birth of a new classless, sexually equal society.

That society did not come to pass. The revivalist movement of the 1830s and 1840s, which reasserted Christian values, and the increasing strength of capitalism in mid-century England created a climate where Owenite ideas no longer flourished. However, feminism – the belief in equal rights for men and women – reappeared in a different form.

Before the 1870 Married Women’s Property Act in Britain, women could not legally own their property, wages, inheritance or gifts. They were not considered to be legal persons. A similar Married Women’s Property Act was passed in Australia in 1883.

Victorian feminism

While the Owenites wished for an ideal communal society, a group emerged in the 1850s and 1860s in Queen Victoria’s England that was far more realistic and practical about the social transformation it wished to achieve. The changing role of women was a key factor in this group’s concerns. Before the Industrial Revolution, women had played a much larger role in the household: growing food, making clothing, washing, cleaning and cooking occupied much of women’s time. The increasing tendency to mechanise production reduced women’s tasks within the household. Some then demanded more meaningful occupations and an education to prepare for it. This new movement for equal rights was led by women, usually from comfortable middle-class families.

Their aims included:

- the right for women to own their own property

- the right to divorce

- the right to work in new expanding occupations, such as clerical work and teaching

- the right to an education equal to their male contemporaries

- the right to higher education

- the right to vote.

While earlier socialist movements had strongly supported the emancipation of women, Marxist socialists (followers of Karl Marx) placed far more emphasis on issues of social class.

Achievements

The women’s movement is often referred to as the feminist movement, although that term was not used until the late nineteenth century. It was one of the major progressive movements of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Women’s lives were transformed through the many changes and achievements of the women’s movement. Men’s lives also changed correspondingly, although not to the same extent.

These are some of the most important changes, which you can research further:

- Women gained the right to own their own property and wages.

- Women gained limited and more equal access to divorce.

- Women began to gain jobs in a greater number of areas.

- Girls gained access to primary education and in some cases secondary education.

- A few determined women gained access to universities.

- In some areas women gained limited access to birth control.

- Women gained the vote on terms equal to men.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 13.10

Imagine that you are a girl or boy aged 15 years and born in 1850 to a blacksmith father and a mother who takes in washing. You have five brothers and sisters. Write a diary entry of a day in your life in an English town or an Australian rural community.

Questions you may like to keep in mind while writing your diary entry include:

- Would you be likely to go to school?

- Would you be working and, if so, where?

- At what age would you expect to get married?

- What rights would you have to control your life?

- Would you be able to vote?

- Would you consider any of these options: joining an organisation to improve your life, migrating to another country or running away to sea?

Remember that the answers might be very different for boys and girls.

Responses to progressive ideas

Most progressive ideas have had to be fought for; for example, not everyone was happy with the claims made by the feminist movement.

While many women rallied to the fight for equal rights, some women felt that they should remain subordinate to their husbands; they believed that men and women had their appointed places in life – men in the public world and women within the private domain of the home. Men and women, they claimed, inhabited ‘separate spheres’. While some women were keen to take up new work opportunities, others thought that working women would undermine men’s jobs, or hurt their husband’s pride. Many men were worried that liberated wives would no longer look after their every need.

Leading clergy and churchmen fought strongly against women’s rights, arguing that God had created men and women for different purposes.

Opponents of women’s rights frequently wrote about feminists as ugly, bitter and unmarriageable, whereas in fact many supporters were attractive women, most were married and they often had families who supported their goals. Those seeking higher education were deemed to be ‘bluestockings’, a term that conjured up an eccentric and unattractive image. Some doctors wrote that education would ‘unsex’ women, detracting from their ability to bear children. Employers did not want to consider giving women equal wages as they preferred to employ them very cheaply, arguing that most could be supported by their husbands. This was not always the case.

Large numbers of women had to work either through poverty or death of a partner, or as single women with no means of support.

The women’s movement in Australia

The women’s movement played a significant role in transforming women’s lives in Australia.

The new colonies inherited many of the ideas discussed in Britain. Some of the earliest convicts were political prisoners, who were jailed and transported for their radical ideas, such as the Irish convicts in Tasmania who fought their British rulers for a free Ireland. Some convicts had Chartist connections and brought those ideas to Australia, influencing, among others, miners at Eureka.

Others had been involved in the movement for women’s emancipation.

Women colonists kept closely in touch with ideas in England and the demands of those wanting equal rights for women were well known here. Many single women migrated to Australia and demanded the right to work. New opportunities were opening up in the growing colonies and, after Federation in 1901, in the states.

Women became teachers, nurses and employees in the developing state administrations. Newly developing societies are often more open to change and in several areas in Australia women were ahead of much of Britain; for example, in gaining access to universities and in relation to the vote and the right to stand for parliament.

Higher education

From the 1860s onwards, many women fought for the right to an education similar to that of men.

With the introduction of universal, compulsory and free primary education, some girls did achieve that equality at elementary level. A small number went on to complete secondary education at either private girls’ schools or the earliest state high schools. Some wished to attend university to obtain degrees and become teachers or doctors, or to join other professions. Some felt that higher education for its own sake was a desirable goal. Initially universities rejected women’s pleas. They argued that university education would make women unattractive ‘bluestockings’.

Alternatively, women might be flirtatious and distract young men from their studies. Overall, opponents argued, what would women do with a university degree? They would marry and have families and the degree would be ‘wasted’. Others feared that women were seeking too much power.

Eventually women prevailed, supported by some male professors with ambitious daughters.

Women were not fully admitted to degrees at the University of Oxford until 1921, while the University of Cambridge held out until 1947. Women were admitted to degrees at certain Australian universities from 1881.

Additionally, some Australian universities did not always attract enough students: women could help to swell the ranks. And the new school systems needed well-trained teachers; accordingly, women were admitted to the universities of Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney from the early 1880s. Now, in twenty-first-century Australia, women make up more than half of all university graduates.

Achieving the right to vote (women’s suffrage)

From the time of the French revolution, some women wanted the right to be full citizens and to vote for an elected government. The Owenites, Chartists and many socialist and feminist groups all demanded this right throughout the nineteenth century. However, opposition was strong on many fronts. Some argued that men could represent their wives or daughters, while others feared that it might break up families if husbands and wives held differing political opinions. The strong belief that women’s place was in the home and not in public life shaped much of the opposition. Yet, contrary to that belief, women were increasingly playing a part in the wider society – in the workplace and in voluntary organisations. A wide range of organisations petitioned parliament for that right, many arguing that women’s voice in public life would ensure a better deal for women and children.

Did you know that in South Australia the Women’s Christian Temperance Union collected 11 600 signatures on a petition supporting women’s suffrage in 1894?

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 13.11

In 1894, South Australia became the first Australian self-governing colony to grant women the right to vote and to stand for parliament.

In 1902, that right was extended to all white Australian women. Australia had been beaten to the post by New Zealand, which gave women the vote in 1893, although it did not give women the right to stand for parliament. English women had to wait until 1918 for that right and then it was only extended to women over 30 years of age. In 1928, women gained full suffrage.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 13.12

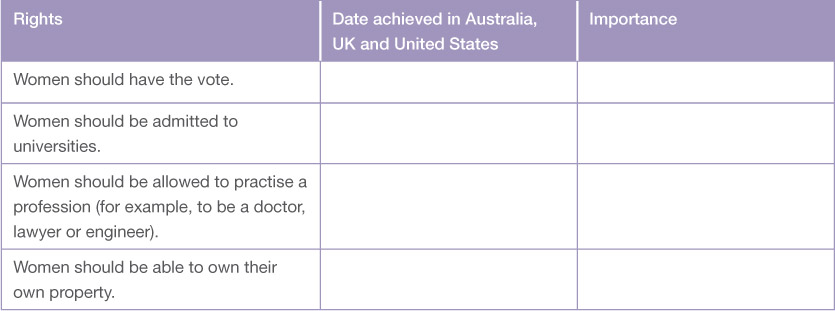

Copy and complete the following table.

| Rights | Date achieved in Australia, UK and United States | Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Women should have the vote. | ||

| Women should be admitted to universities. | ||

| Women should be allowed to practise a profession (for example, to be a doctor, lawyer or engineer). | ||

| Women should be able to own their own property. |

Long-term impacts of the women’s movement

The long-term impacts of the struggle for women’s rights in Australia are spectacular. Women can now vote, stand for parliament and even become the Prime Minister, as Julia Gillard has shown. We have had a female Governor-General, Quentin Bryce, and many other senior women politicians, business leaders and university professors. Women can join the army, become engineers and mechanics, and fly jet planes. Equal numbers of girls and boys finish school and go on to university. The hard-fought struggle for the right to birth control has revolutionised the Australian family. Women now usually wait longer before having babies – the average age at first birth is almost 30 years.

They also have fewer babies than in the past. The average completed family in Australia has fewer than two children. Women have many more years in which to complete education and training, and to establish careers. They also often return to jobs and careers after their children are in childcare or at school. In theory men and women earn equal pay, although in practice this is rarely the case. Divorce is now available equally to men and women, and women can retain their own property and earnings. Both women and men can form legally accepted partnerships with same-sex partners.

Should we argue, then, that the women’s movement has had its day, or that it is no longer necessary? Some women’s groups are still concerned about a range of issues involving relations between males and females. There are concerns about violence towards women and also about how women and men can lead full lives as workers and parents without more assistance, such as an affordable childcare system.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 13.13

Choose several people to each play the part of a prominent thinker discussed in this chapter. Each ‘thinker’ may have a team to help them prepare their case and assemble their argument. Each ‘thinker’ has 5 minutes to convince the class as to why their ideas are still vitally important in modern Australia. A class vote will decide the winner.

RESEARCH 13.3

Use the internet or library to explore one of the following ideas in more detail:

- Darwinism

- nationalism

- imperialism and anti-colonialism (look at these together).

Be sure to research the major aspects of the movement you choose. Gather information about its place in our lives today. How much influence do you think the idea you have chosen has had on our contemporary world? Is this idea still controversial? Present your findings to the class orally.