13.2b Role of progressive ideas in major social upheavals: Reasons for the emergence and development of key ideas

Setting the scene: the Industrial Revolution

Ideas do not spring from nowhere: changing circumstances and new technologies lead to new challenges and new ways of thinking. Think about how the internet has changed so many things we do. From the 1750s the Industrial Revolution in Britain changed patterns of agriculture, developed manufacturing processes for cheaper production of goods, created a wealthy middle class, and exploited cheap labour from those who had been excluded from working on the land. These social changes led to widespread uncertainty, and sometimes bitterness and envy.

One of the reasons for envy was the emergence of very wealthy merchants and industrialists: the new class of capitalists.

Capitalism

This was the period of rampant capitalism. Also known as the free-market economy, or free enterprise economy, this is an economic system that has been dominant in the Western world since the breakup of feudalism. Within this system, most of the means of production are privately owned and production is guided, and income distributed, largely through the operation of markets. Although the continuous development of capitalism as a system dates only from the sixteenth century, earlier versions of capitalist institutions existed in the ancient world, and centres of capitalism existed during the later European Middle Ages.

Capitalism brought much wealth to industrialising countries such as Britain and the United States, but the vast profits made were unevenly distributed.

Many workers were poorly paid and the fact that many capitalist owners were making huge profits led to unrest and rebellion. Children were often employed in dirty and dangerous work. The increase in factory production led to a decline in the handicraft skills of artisans, guilds and journeymen. Many of these formerly independent workers found themselves and their families dependent on low wages and insecure working conditions – even in poverty.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 13.4

Capitalism has been viewed as a natural companion to democracy.

- Discuss whether capitalism always accompanies democracy.

- List some countries that have a capitalist system but a non-democratic society.

- Research others that are democratic but do not embrace capitalism. You may like to consider Denmark and Sweden in your investigations.

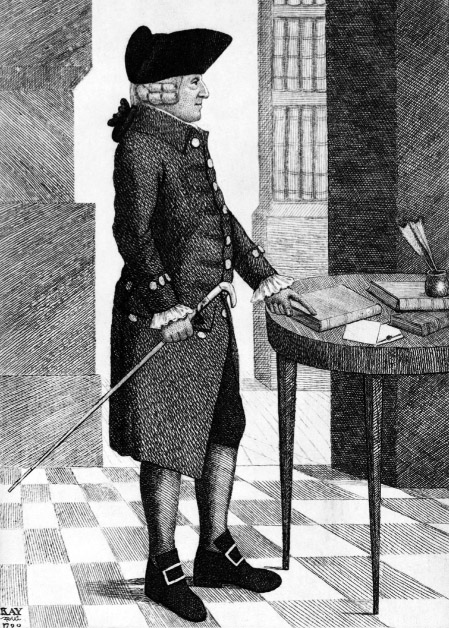

Adam Smith was a typically absent-minded professor. He once made himself a cup of tea from bread and butter. He declared it a very bad cup of tea!

Adam Smith (1723–90)

Adam Smith was a Scottish philosopher and political economist whose work has had a lasting impact on economics. He was one of the major thinkers of the Scottish Enlightenment, as was his friend the philosopher and religious sceptic David Hume.

In 1776, Smith wrote the influential work The Wealth of Nations in which he argued that rational self-interest in a free market leads to economic well-being. He has often been characterised as a supporter of unbridled capitalism and of the idea, in contemporary terms, that ‘greed is good’. Yet in an earlier book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), he argued that human nature contains a predisposition to caring about the welfare of others.

Smith’s work has had great influence: his ideas can be found in the work of others such as Karl Marx and the twentieth-century economists John Maynard Keynes and Milton Friedman. There is considerable debate about some of his major ideas, such as the importance of his use of the term ‘an invisible hand’ – the idea that the market works inevitably towards equilibrium; that markets are self-regulating. Smith was ahead of his time in setting out the idea of the division of labour. He argued that while a single worker in a pin factory could produce only one pin a day by themselves, if tasks were divided and specialised, 48 000 pins a day could be produced. He also opposed colonialism on economic grounds.

Many of Adam Smith’s works are available online:

The Wealth of Nations – https://www.cambridge.edu.au/redirect/?id=217

The Theory of Moral Sentiments – https://www.cambridge.edu.au/redirect/?id=218.

Robert Owen (1771–1858)

Not all factory owners were greedy monsters who exploited their workers. A few cared deeply about their workers. One in particular, Robert Owen, a businessman and social pioneer, was inspired by the progressive moral views of the 1790s. He put these ideas into practice at the cotton mills of New Lanark, Scotland, where he established a model community to improve the lives of workers. There he established the first infant school in the world, a crèche for working mothers, free medical care, an education system for children and evening classes for adults. He was committed to the ideal of female equality. He also insisted that children under the age of 10 years should not work.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 13.5

Collectivism

One of the results of the changes brought about by the Industrial Revolution was that disaffected people began to organise themselves into groups, realising that collective action to improve their lot would be more effective than individual action.

In contrast to individualism, which sees the rights and interests of individuals as more important than anything else, collectivism sees the individual as subordinate to a social collectivity such as a state, a nation, a social class or a race. The idea of collectivism is implicit in the idea of the modern state, which is portrayed as acting for the good of all. One of the most significant writers to develop this idea was the Swiss philosopher and novelist Jean-Jacques Rousseau. In the book The Social Contract (1762), Rousseau claimed that true being and freedom could be obtained through submission to the laws of the state.

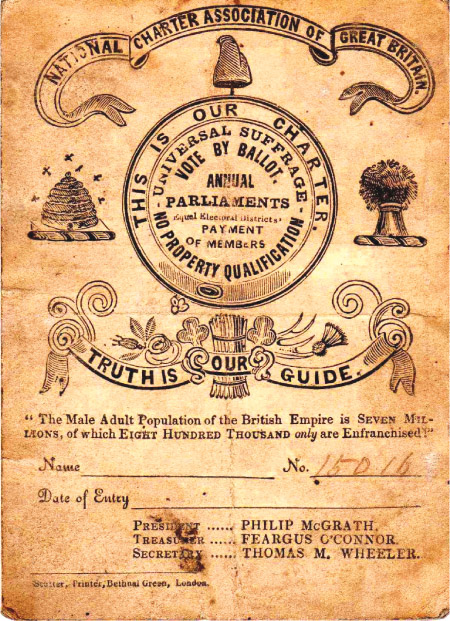

Chartism (1838–50)

Chartism was a collectivist movement of British working men and women who from 1836 sought to gain wider parliamentary representation in order to improve their lives. The full text of the People’s Charter is available online at https://www.cambridge.edu.au/redirect/?id=219. The movement followed the Reform Act of 1832 in Britain that gave the vote to middle-class men. Its name comes from the People’s Charter, which was a direct response to the deteriorating working and living conditions of the early nineteenth century. Chartism has been described as the first nationwide mass movement of working people – an expression of working class consciousness. The movement maintained a strong faith in parliament to bring about social change.

In 1839, 1842 and 1848 millions of Britons signed petitions for parliament to implement the Charter, without success. After several mass public gatherings, a wave of strikes and several riots, Chartism faded after 1850. However, its legacy was strong, giving an impetus to parliamentary reform for decades to come.

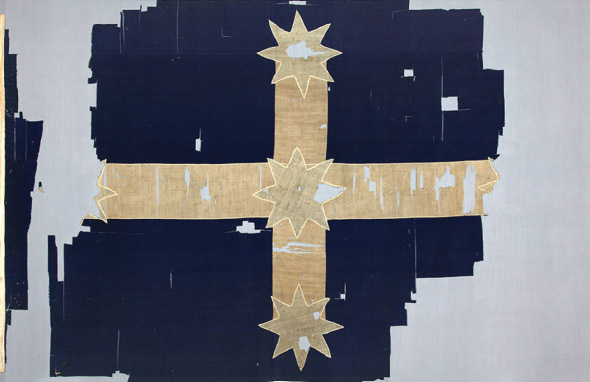

The Chartist movement had strong links with Australia. It has been estimated that 102 Chartists were transported to Australia as convicts in the wake of the three successive Chartist peak years of 1839, 1842 and 1848. Recently, Australian historians have traced the way in which both convict and free settler Chartists used their influence in the Australian colonies to bring about the near complete acceptance of the Charter demands in Australia, well before they were enacted in Britain. Chartist ideas were at the root of many workers’ struggles, including the rebellion over mining licences that culminated with the famous battle at the Eureka Stockade.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 13.6

- Describe some of the symbols that we associate with Australian nationalism.

- List some of the key dates on which we celebrate the Australian nation.

- Describe the ways in which nationalism can be a progressive force.

- Research examples where nationalism has had a less positive side. (You might think, for instance, of the ways in which some newcomers to a country might feel excluded.) Consider countries other than Australia in your answer.

- Decide if you think there is there a link between sport and national identity.

- Determine what people mean when they accuse someone of being ‘un-Australian’.

- Analyse the ways in which the Eureka Stockade contributed to Australian identity.

Nationalism

The French Revolution is also credited with boosting the idea of nationalism. Nationalism involves a strong sense of identity with a particular community – for example, a strong sense of being Australian. This usually involves a strong pride in ‘one’s country’, a sense that the interests of the state are supreme, and in some cases a willingness to make sacrifices for it. There are two main types: state nationalism, which is imposed by the state (top down); and popular or grassroots nationalism, which springs from a sense of belonging to a particular national or ethnic group (bottom up). Some Australians, for example, might feel that their indigenous, Vietnamese or Greek identity, for example, overrides their sense of belonging to the Australian nation. Perhaps it coexists beside it.

Although we tend to take nationalism for granted, it is a fairly recent idea historically.

It gained strength during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as many nation-states were created. For example, there was no British nation until 1707. Before that people thought of themselves as English, Welsh, Scots or Irish. Italy was only created as a ‘nation’ in 1861.

State systems of schooling help to build national identity and culture, as do ceremonies and symbols such as flags, ‘national’ anthems and national dress. In some nations, only one official language is permitted to flourish at the expense of the languages of minority groups.

There is considerable debate as to whether nationalism is a progressive idea or one that leads to division and conflict. Perhaps it can be both.

Imperialism

Imperialism has been defined as the policy of extending the rule or authority of an empire or nation over foreign countries, or of acquiring and holding colonies and dependencies. This was not a new idea in the modern world. Indeed, the Persians, Greeks and Romans all acquired empires and colonies in ancient times. The Ottomans and Austro-Hungarians built large empires in early modern times. However, from the 1870s on, there was a scramble by the major European powers for the control of countries whose goods and people could be exploited for gain. In fact, from 1875 to 1895, more than 25% of the world’s land was seized by European countries. Associated with imperialism (but not the same thing) was colonialism, where major powers planted colonies of their citizens on the soil of another country, as was the case in Australia.

Although by no means a progressive idea, imperialism is an important concept for an understanding of the modern world as it did much to shape global politics in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The struggle against imperialism gave impetus to many progressive movements, including nationalism, egalitarianism, anti-colonialism and anti-racism.

Socialism

Strongly opposed to imperialism and also, in effect, an opponent of nationalism, socialism is another social movement that arose from the collectivist and cooperative impulses of the early nineteenth century.

Socialism was based on the understanding that the poor, the weak and the oppressed would only gain a tolerable life through the pooling of resources and the fair and equal distribution of wealth. It was part of a collectivist response to the major upheavals of the Industrial Revolution and to growing capitalist wealth. We have already seen that the response to the deteriorating working conditions led to the formation of cooperatives, trade unions and reformist groups such as the Chartists. Socialism sprang from several strands of collectivist thinking: from aspects of Christian doctrine, from trade unionism, from the formation of cooperatives and from the ideas of French thinkers such as Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, Louis Blanc and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. It has had a profound effect to this day.

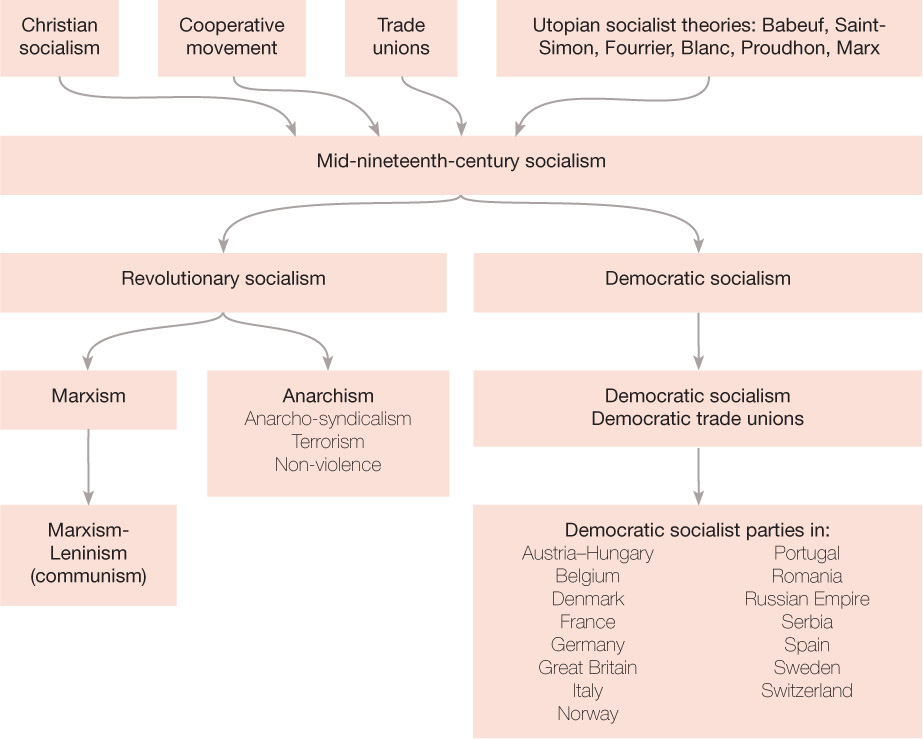

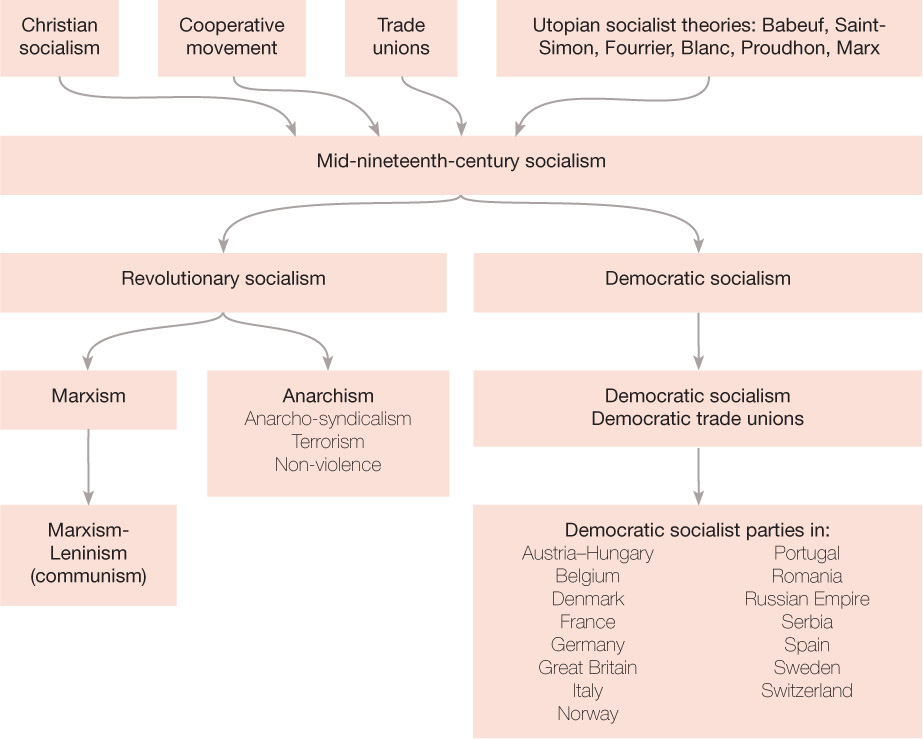

Socialism is often divided into two main strands. The first is revolutionary socialism, which led to Marxism. The other major strand is democratic socialism, which has inspired, and still inspires, many political parties throughout Europe and the globe (see Source 13.10).

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 13.7

Imagine that you live in a country that has been made part of the empire of another (for example, you might be an Indonesian person who was part of the Dutch empire in the eighteenth century).

- Describe how you might feel about the colonising country. What opportunities might be available to you through colonisation? What ill effects might it bring?

- Propose the Enlightenment ideas that you might draw on to argue for your freedom from the colonisers.

Karl Marx (1818–83)

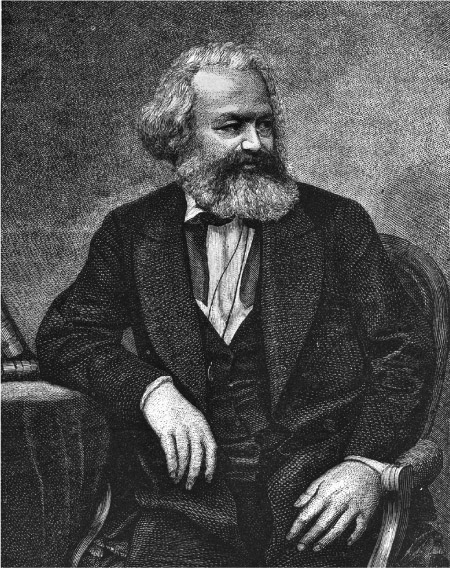

Karl Marx, a philosopher, social scientist and historian, was a towering figure whose work had an enormous influence on the world of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Marx, a German, was exiled from his country for his revolutionary views. Writing from his new home in London, Marx and his fellow German exile Friedrich Engels wrote The Communist Manifesto (1848), which subsequently inspired revolutions across the globe. Marx also penned Das Kapital (Capital, 1867–94), his three-volume life work.

In Capital, Marx drew on the ideas of many previous thinkers expressed during the Enlightenment period in an attempt to create a universal theory for human society, just as Darwin had done for natural history. Seeking to uncover the laws of human history, Marx proposed stages of history and an eventual withering away of the state. Marx also helped found an International Workingmen’s Association.

In many ways the extraordinary influence of his work is due as much to its emotional power as to its intellectual rigour. Words such as the following from The Communist Manifesto inspired those opposed to the exploitation of workers by the bourgeoisie: ‘A spectre is haunting Europe, the spectre of communism. Let the ruling classes tremble … The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains … Working men of all countries unite.’ Marx is buried at Highgate Cemetery in London. The inscription on his tombstone reads: ‘Philosophers have so far explained the world in various ways: the point, however, is to change it.’ Marx’s writing has certainly changed the world. It contributed to some of the major revolutions of the twentieth century – such as the Russian and the Chinese revolutions – and inspired many contemporary regimes.

Charles Darwin (1809–82)

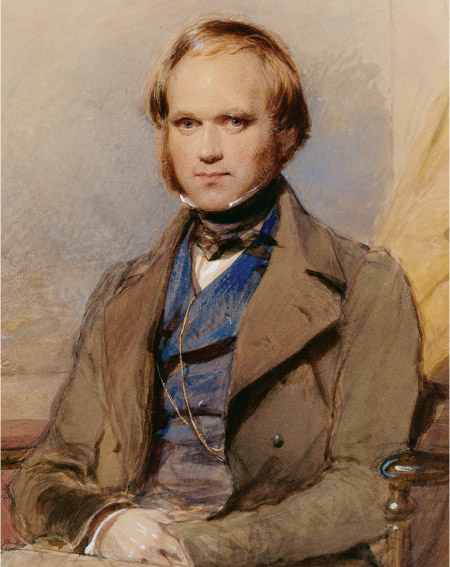

Charles Darwin is another man whose challenging ideas had a significant influence on the progress of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Darwin was an English naturalist whose theories of evolution and natural selection – commonly known as ‘the survival of the fittest’ – shook the establishment of his time because it challenged the biblical notion that the world was created by God in 6 days and 6 nights. This was a religious belief widely accepted in the mid-nineteenth century.

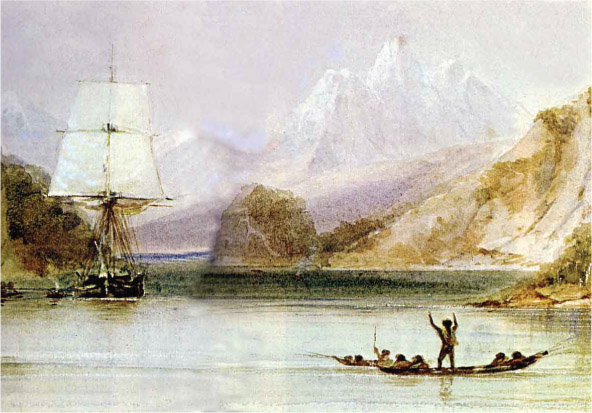

As we have seen, the Enlightenment created a climate where scientific ideas could flourish, yet their acceptance in educated circles was often controversial. Darwin spent 5 years travelling the world on the ship HMS Beagle, particularly collecting data in South America and the Galapagos Islands. He observed that ‘all living species of the plant and animal world have progressed through constant interchange with their environment and with competition among themselves’. Darwin argued that all humanity came from a common ancestry in the distant past, a theory that we have fully accepted now. The notion that humanity might have descended from apes shocked the religious establishment of the mid-nineteenth century, which firmly believed that animals and humankind inhabited quite separate universes.

Darwin argued that evolution means that we are all distant cousins – humans, birds and mammals – a revolutionary thought to many at that time.

RESEARCH 13.1

In a short report, explore what is meant by the idea of natural selection, otherwise known as ‘the survival of the fittest’. Trace the steps by which Darwin came up with this theory. After Darwin’s evolutionary ideas had been widely accepted, some thinkers put forward a notion of social Darwinism.

Was this a progressive idea? Could this idea be used to support imperialism?