13.1 Emergence of key ideas

The Enlightenment (1650–1770)

The seventeenth to eighteenth century Enlightenment, sometimes known as ‘the age of reason’, was a major seed bed for progressive ideas. This was a period when scientific knowledge flourished.

A range of thinkers – including John Locke, David Hume, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Voltaire – began to draw on reason rather than religion or myth to uncover the ‘rules’ of the human and natural worlds.

Their focus on reason and the ability to think for oneself led to fertile debates between reason and faith. They threw off superstition and sought to throw light on the supposedly dark world of medieval religion. They questioned the authority of the church and state and the absolute right of monarchs to rule. Many developed a concern with ‘natural rights’, the forerunner to the current concern with ‘human rights’.

The ideas of the Enlightenment spread widely through many different countries. In Britain, the United States and, later, Australia, many of these views were discussed in groups such as literary and philosophical societies and mechanics institutes.

Enlightenment ideas also underpinned two major upheavals of modern times: the American War of Independence and the French Revolution.

Thomas Paine and Mary Wollstonecraft, two well-known English writers, lived and breathed Enlightenment ideals and wrote influential works that contributed to the spread of those ideas.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 13.1

Thomas Paine (1737–1809)

Thomas Paine, the son of an English Quaker and corset maker, had a profound effect on the American Revolution. After a meeting in London with the American ‘Founding Father’ Benjamin Franklin, Paine migrated to America in 1774 where he wrote the revolutionary pamphlet Common Sense (1776). This widely read pamphlet offered a strong defence of American independence from England and argued for the establishment of a republican constitution. Paine’s writing was often called ‘the voice of the common man’ and his work was widely circulated. Paine’s book The Rights of Man, written in 1791 as a response to the French Revolution, was strongly anti-monarchist. It argued that all men are equal in the eyes of God and therefore they should all have political rights. His strong democratic republican views forced him to flee England for France and he became a French citizen in 1792.

He opposed the most radical aspects of the French Revolution, however, and did not support the execution of King Louis XVI. Imprisoned, he wrote The Age of Reason (1793), a strong and fiery case against the established Christian church.

Paine later returned to America where he died, shunned by many former supporters because of his anti-Christian stand. ‘My country is the world,’ he wrote, ‘and my religion is to do good.’

Many of Thomas Paine’s works are available online:

Common Sense – https://www.cambridge.edu.au/redirect/?id=211

The Rights of Man – https://www.cambridge.edu.au/redirect/?id=212

The Age of Reason – https://www.cambridge.edu.au/redirect/?id=213.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 13.2

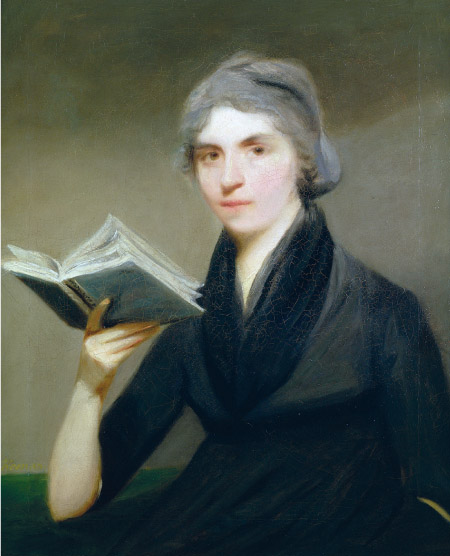

Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–97)

While men such as Paine wrote about the equality of all men, hardly any considered women to be their equals. Mary Wollstonecraft, however, felt strongly that women should have the same rights as men, particularly in relation to education.

Mainly self-educated, she became a lady’s companion, school teacher and governess, which were occupations typical for women of her class.

A position as an editorial assistant to the radical publisher of the magazine Analytical Review enabled her to focus on writing and to develop her literary skills. Her work as a governess gave her an abiding hatred of the situation of intelligent women dependent on the rich and uneducated, and led to her book Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (1787).

In it she stressed the importance of reason in the education of both girls and boys, and deplored the focus on instinct and sentimentality for girls.

Wollstonecraft also wrote A Vindication of the Rights of Men, followed by her best-known work, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792).

Many of Mary Wollstonecraft’s works are available online:

Thoughts on the Education of Daughters – https://www.cambridge.edu.au/redirect/?id=214

A Vindication of the Rights of Men – https://www.cambridge.edu.au/redirect/?id=215

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman – https://www.cambridge.edu.au/redirect/?id=216.

Like Thomas Paine and other English intellectuals, Wollstonecraft was enthusiastic about the possibilities of the French Revolution and travelled to France in 1792, where she lived with the American, Gilbert Imlay.

Wollstonecraft is one of the ‘founding mothers’ of feminism: the belief that women should have the same rights and opportunities as men, and that men and women are basically equals. This flew in the face of the thinking of her time, which viewed women as ‘the weaker sex’, inferior to men and dependent upon them. Wollstonecraft advocated equal educational opportunities as a right for girls, claiming that well-educated women would make better wives and mothers.