12.3 Changes in the way of life

Free settlers on the Australian frontier

From Skye to the Western Australian frontier

In 1854, Samuel and Janet Mackay and their family left the Isle of Skye, Scotland for Australia. A poor family with nine children ranging in age from 6 to 24 years, they could not survive on their income, let alone pay the rent of their tiny 1-acre (0.4-hectare) croft.

They were seen as ‘poor but respectable’, but landlords wanted to run sheep on their estates and to clear such people off their land. The Highland and Island Emigration Society helped to pay their fare and they arrived in Australia owing about £50 for their passage. While the young ones looked forward to life in Australia, the older ones must have been heartbroken at leaving their beloved Skye, the home of their ancestors.

A strange wailing sound reached my ears … I could see a long and motley procession winding along the road that led north from Suishnish … There were old men and women, too feeble to walk, who were placed in carts; the younger members of the community on foot were carrying their bundles of clothes and household effects, while the children, with looks of alarm, walked alongside … Everyone was in tears.

Source 12.19 An eyewitness records the tragic scene during the Skye clearances in 1854.

Samuel had hoped that he would be granted farmland, but the family was seen as suitable only as station hands and farm servants. They were sent to the south-east of South Australia and began working for pastoralist Robert Lawson on Padthaway station near Naracoorte. The older sons began to learn Australian bush craft while their parents were hut-keepers at a distance from the station homestead. They had to look after the sheep and make sure they had water. The change from the crowded misty Scottish island, with relatives and friends all around them, to the isolated hut in the summer of Australia was difficult for Samuel. In January 1856 he died from dysentery.

The older sons Roderick, Donald and Donald McDonald (Dody) worked as drovers, stockmen and overseers in the pastoral industry in South Australia and western Victoria. Two of the daughters, Catherine and Mary, helped their mother to run a school in Mount Gambier, where they were seen as respectable members of the community and in their Presbyterian church.

The lands of the south-east had been wrested from the Buandig peoples in the years before the Mackay family arrived. As the Mackay family grew in prosperity, the Buandig peoples were becoming beggars. The missionary Mrs Smith wrote about the decline of this ‘once numerous and powerful tribe of South-Eastern natives’ due to ‘the new mode of life forced upon them by the advent of European colonists in their midst, assisted too often by the cruelties practised upon them by the early settlers’. Other Indigenous people were dying from diseases introduced by the Europeans, along with the loss of their families and the land of their ancestors. Where they were employed on the stations, they were paid only with food and clothing.

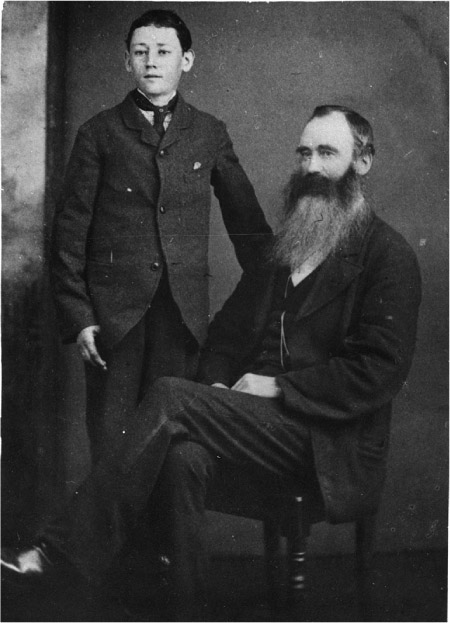

The Mackay brothers were keen to get rich and were saving up their wages from doing station work. Even 12-year-old Donald drove a bullock team loaded with wool bales for 110 kilometres to Guichen Bay. In 1864, Roderick was part of a group of ambitious young men of Scottish background who wanted to get pastoral land in the north-west of Western Australia. They formed a company and sailed to the region to explore and take up land. This was a harsh country and a number of times Roderick had to return to South Australia to get more stock and start again. Dody joined him and by 1872 they were doing well at Maitland River, but then a cyclone swept away 1400 of their 2000 sheep.

They set off to find new land and established Mundabullangana, near present-day Port Hedland.

They selected more than 1 million acres, with a frontage of 30 miles along the Yule River. The plains of the Kariara people were of ‘rich chocolate soil, covered with various succulent grasses and fattening shrubs, with a large proportion of soft spinifex’ – good land for sheep. Donald joined his brothers and by the year 1879 they ran 18 000 sheep, ‘all shepherded by the aborigines’. Soon their wool was sold in London, bringing them great profits.

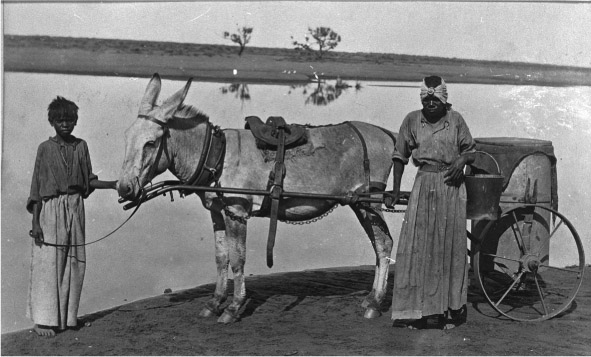

They used the land and the labour of the local Aboriginal people, whom they paid with food rations and clothing. Aboriginal people built 800 kilometres of fences by 1890 and did all the shearing and drove the bullock teams.

Indentured labourers from Manila, China and Malaya also worked for them, sinking wells, growing vegetables and cooking. The Mackay brothers bought other stations in the Pilbara – Roy Hill, Sherlock, Mallina and Croydon – and their landholdings grew. The Mackays built a fine homestead to live in with their wives and children.

The homestead is a mansion, built mostly of a kind of bluestone, and is so constructed as to provide the most comfort during all seasons. On approaching the homestead the visitor imagines he has discovered a miniature town, so numerous are the buildings.

Source 12.22 A visitor describes the homestead at Mundabullangana, 1907

The Mackays were described as ‘a strong, violent family’. They also had pearling luggers (boats) working off the coast, and Dody hired ‘depraved and vicious’ men to capture Aboriginal people from inland to dive for pearls. This was seen as ‘a system of organised slavery’. In 1887, Donald and his son Samuel were accused of shocking treatment, such as whipping the Aboriginal people on their luggers and stations.

In 1879, tragedy struck the Mackay family when Roderick Mackay was lost at sea in his pearling lugger during a cyclone. Donald and Dody kept the stations. But during the 1890s drought, Dody sold his share and went to Perth. In 1896, he was elected a member of the Western Australian Legislative Council to defend the interests of the northern pastoralists. When Donald and Dody died they left a large amount of money to their families. Dody’s funeral in 1904 was in grand Scottish style and was attended by the important citizens of Western Australia. The Mackay family had come across the world from a life of poverty on Skye and had become wealthy and powerful in Australia, but at great cost to the Aboriginal people they had exploited and displaced.

RESEARCH 12.2

- Research the life of one of the following convicts:

- Edward Davis

- Francis Abbott

- Francis Greenway

- Hannah Rigby

- John Black Caesar

- John Davies

- Margaret Catchpole

- Maria Lord

- Mary Bryant

- Mary Reibey

- Maurice Margarot

- Molly Morgan

- Simeon Lord

- William Blue

- William Buckley.

- Use the internet and other sources to research the situation of Aboriginal people in the Roebourne area today.