12.2d Era of mass migration: Free settlers

White settlers to Australia

Free settlers coming to Australia travelled in much better circumstances than did the convicts. Janet Snodgrass travelled to Australia from Glasgow in 1886 on the Loch Long. She travelled with her five young children to join her husband who was building a home for them. They hoped to improve their lives in Australia.

As the long voyage began, she and all her children were seasick and vomiting. Her little son Matt ‘got very cross and wanted me to stop the ship, and not let it go on that way’. Such middleclass passengers were well looked after, as Janet experienced when the steward made a plum pudding for her son Alan’s birthday. She passed her days talking to other passengers. Religious services were held on deck and passengers also enjoyed concerts and other entertainment. As they crossed the Equator, her sons Matt and Hugh had great fun with King Neptune; they ‘were both shaved, then they have to swallow a big pill and are pitched head first into a big sail filled with water, and ducked three times’. On arrival, her husband met her and the family went out to his farm at Colac in Victoria, where they were building ‘a nice little weatherboard house’. With the steward looking after her family, this was a comfortable trip. During the nineteenth century, there were several different classes of travel, largely based on the class of the passengers themselves and the lives they had been accustomed to living in their old country.

Free settlers?

Many of the Europeans who migrated to the New World and Australia in the nineteenth century were destitute and had no real choice to stay in their homelands. Scots from the impoverished Highlands were assisted by emigration societies who paid part of their fare to Australia or Canada during the 1850s. The highlands and the western islands of Scotland were overpopulated. Families were being evicted from their land or crofts as they could not pay their rent. Many were close to starvation. Donald and Effy McFarlane had seven children. After their croft was lost, Donald tried to earn money catching lobsters and other shellfish.

They lived in one room and had little food. Such a family, with so many children who would grow up to be workers, would be an asset in Australia.

In Scotland they were just a charity burden. Once in Australia they would have to save to pay back £44 3s 1d, which was part of the cost of the trip to Australia.

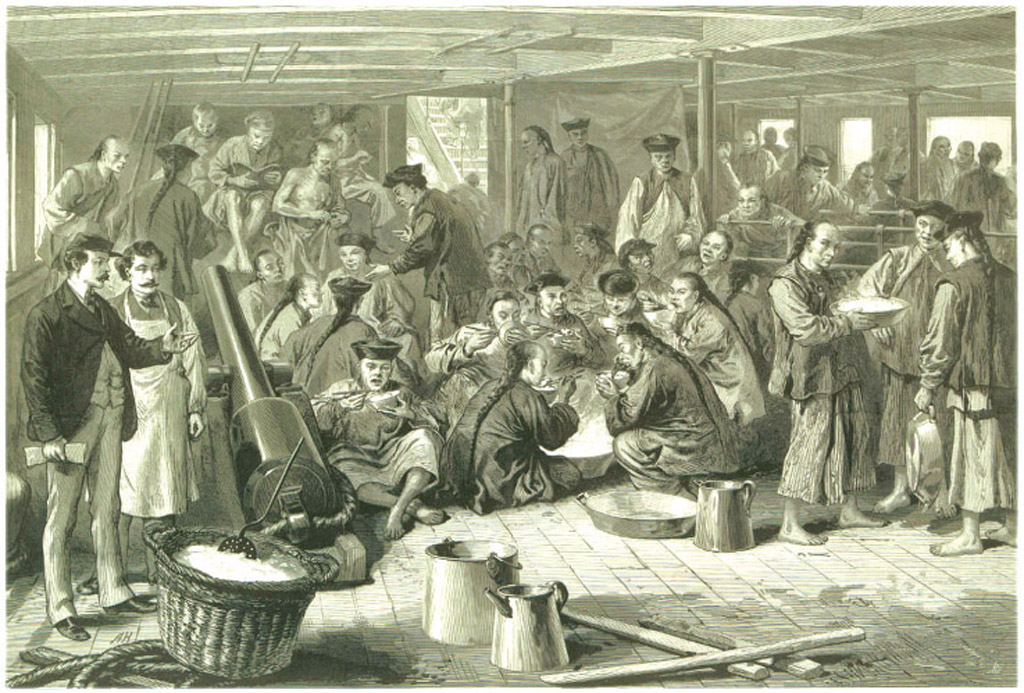

The food supplied for the voyage was high in carbohydrates, with some protein. Many ate better on board ship than they had for years. The James Fernie, bound for South Australia, left Liverpool with 350 assisted Scots and Irish migrants in 1854.

While the food was plentiful on this ship, some of the passengers carried cholera on board and 28 passengers died during the voyage.

Rations provided per week per adult passenger over the age of 14 years on the James Fernie were as follows (note that 1 ounce equals 28 grams and 1 gill equals approximately 140 millilitres):

- 56 ounces of biscuit

- 6 ounces of beef

- 18 ounces of pork

- 24 ounces of preserved meat

- 42 ounces of flour

- 21 ounces of oatmeal

- 8 ounces of raisins

- 6 ounces of suet

- ¾ of an ounce of peas

- 8 ounces of rice

- 8 ounces of preserved potatoes

- 1 ounce of tea

- 1½ ounces of ground coffee

- 12 ounces of sugar

- 8 ounces of treacle

- 4 ounces of butter

- 21 ounces of water

- 1 gill of mixed pickles

- ½ ounce of mustard

- 2 ounces of salt

- ½ ounce of pepper.

Children aged between 10 and 14 years received two-thirds of this allowance and children aged between 2 and 10 years received half.

The potato famine and the Irish diaspora

During the nineteenth century and the first two decades of the twentieth century, around 8 million people left Ireland for the New World, chiefly North America and Australia. As well, many settled permanently in England and Scotland. In relative terms, more people left Ireland than from any other European country.

Poverty-stricken Irish peasants depended upon the potato for their survival. When the crop failed in 1845 due to a disease, thousands of people were desperate. Landlords evicted those who could not pay their rent. Many people were starving and had no choice but to leave in the hope of finding a better life. Landlords and Poor Law guardians often paid fares to get rid of these paupers. The famine set off a huge tide of emigrants from Ireland. Between 1846 and 1855, 2.5 million people emigrated, and between 1856 and 1914 another 4 million departed.

Migrant ships and coffin ships

Due to the potato famine, many migrants were destitute; they came to the ships in rags, bareheaded and often without shoes. Many were malnourished and sick. The conditions on the ships were very crowded and unhealthy. Bunks were shared with four people on a bed 1.8 metres long and 1.8 metres across. Ship owners could evade regulations – one ship to Canada in 1847 had 276 people sharing 36 berths. Passengers had to provide much of their own food, or try to survive on the 3 kilograms of food and 2 litres of water that ship-owners were required to supply weekly. On the worst ships, typhus and dysentery spread. Vomit and excrement dripped through the tiered bunks on to passengers below.

So many died on the voyage to North America in the 1840s that these were called ‘coffin’ ships.

Over the years, the standard of shipping improved, but wherever they went, the Irish – who often spoke only Gaelic, and who were fleeing from the famine – were looked down upon as ignorant ‘savages’.

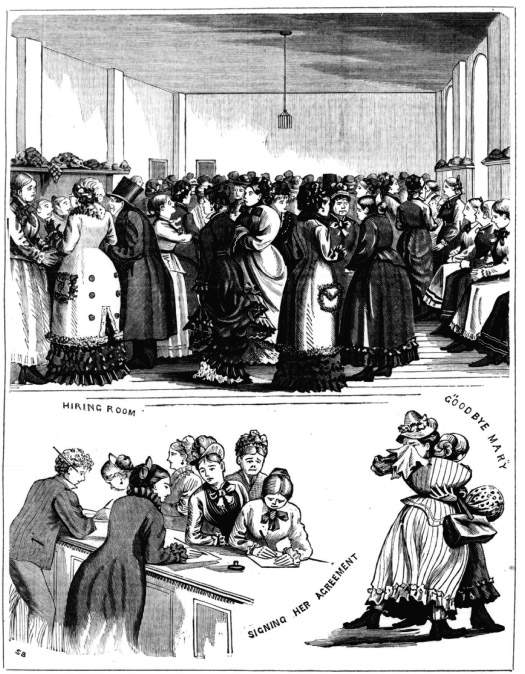

Many Irish fled the famine and made the long journey to Australia. In 1849, 16 orphan girls, some only 14 years old, were sent to Australia on the Ballyshannon in the hope that they would become servants, marry in Australia and make a better life. Certainly these girls were fitted out with new clothes for the trip, and given better food.

While waiting for work they stayed in Hyde Park Barracks in Sydney and at depots in Melbourne, Adelaide and Brisbane. Many in Australia opposed their migration, seeing them as poor servants with no domestic training. They were seen as disobedient, users of bad language and potential prostitutes. Some made good lives for themselves, while others, broken by the hardships of their young life and the loss of family, found it hard to adapt.

Prejudice

In both Australia and the United States, there was a lot of prejudice against the poor Irish migrants.

Members of elite Protestant groups saw them as ignorant, dirty and responsible for crime. In the United States, Irish were told they need not apply for certain jobs, as they were not wanted.

One Chicago newspaper wrote: ‘The Irish fill our prisons, our poor houses … Scratch a convict or a pauper, and the chances are that you tickle the skin of an Irish Catholic. Putting them on a boat and sending them home would end crime in this country.’

When an Irish person was migrating to America, their family and friends held an American wake for them. This was a farewell to the migrant, whom they never expected to see again. Like a wake after a funeral, a eulogy was given about the migrant. In more prosperous homes there would be singing and dancing, but often there was only wailing and despair.

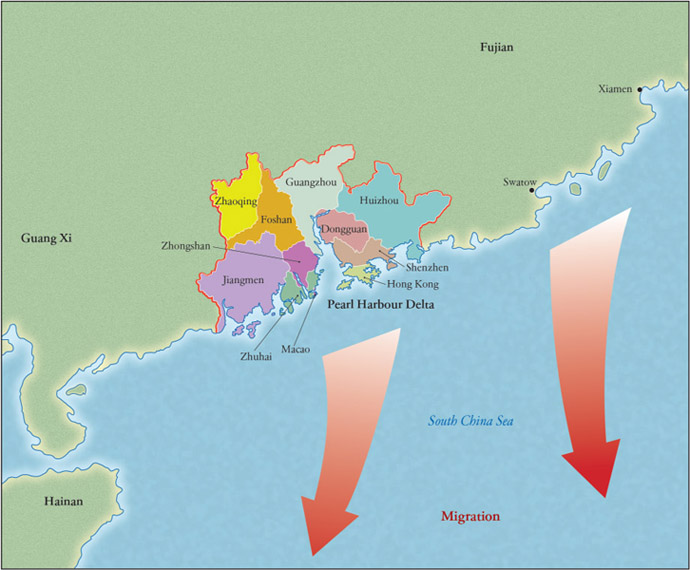

Chinese settlers to California and Australia

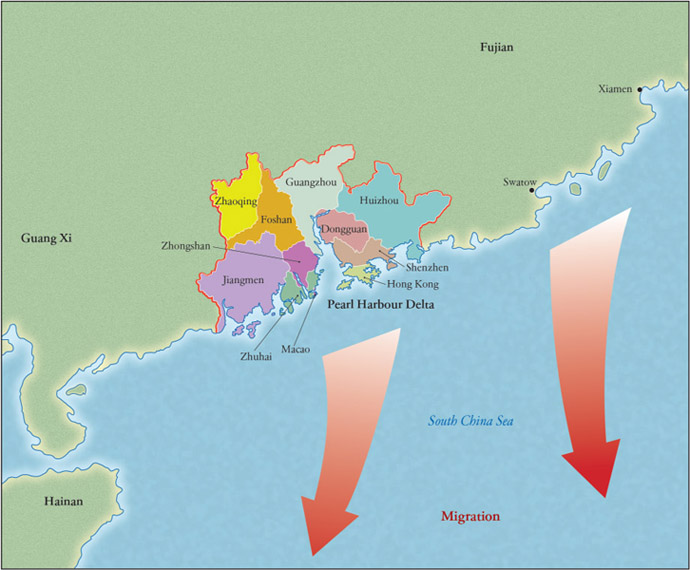

During the nineteenth century, many Chinese people left China in search of work and a better life. Many hoped to return to China someday, but could not. Their descendants live in a number of countries across the world today. In the nineteenth century, life and security in China were threatened by the Second Opium War (1856–60) and the Taiping Rebellion (1850–64). These led to the disruption of agriculture and other economic activities. High taxes and floods forced many off the land, especially in the southern provinces.

Peasants lost their livelihoods and looked for new opportunities. Many Chinese people travelled to nearby countries in Southeast Asia, often as indentured labourers. With the end of the transportation of convicts to Australia, pastoralists were looking for cheap labour and about 3000 Chinese men travelled as indentured labourers to New South Wales between 1848 and 1853. They worked as shepherds and fence-makers, and did other heavy work.

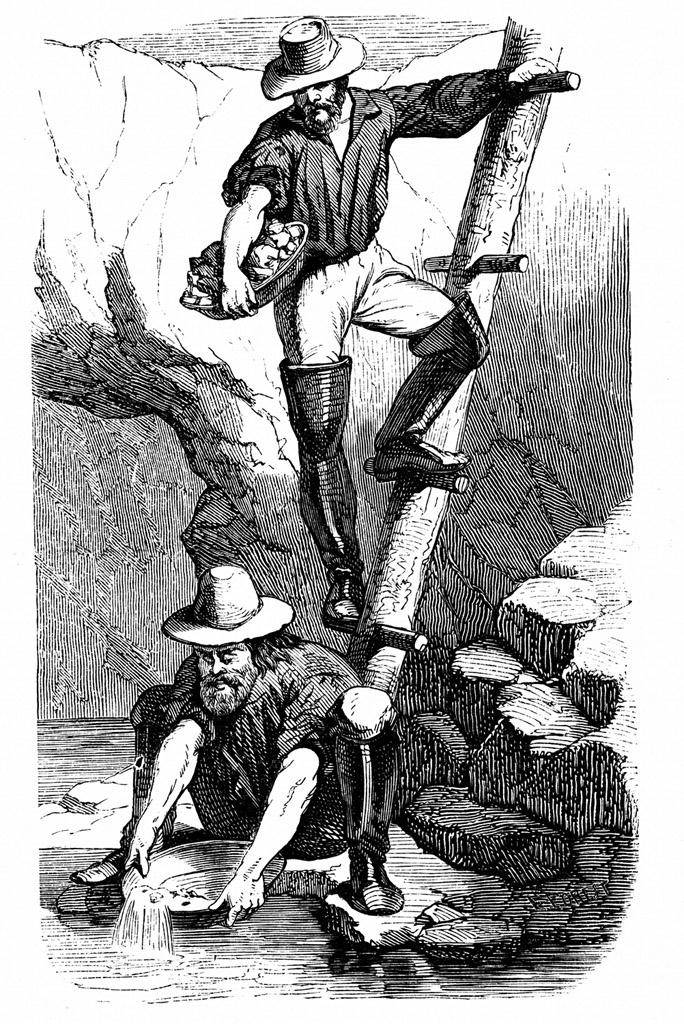

Gold mountain (Gam Saan)

In the late 1840s, when Chinese sailors told them of the discovery of gold in California – that this was Gam Saan, or a gold mountain – many Chinese men set off to make their fortunes. Many could not read, but like the goldminers from Europe, South America and Turkey who were also flooding into the gold fields, they hoped to do well. Very few Chinese women went to California as their husbands planned to return home and a woman was needed to care for her parents-in-law.

Migrants often purchased a credit ticket, which required them to pay back their fares from their earnings from the ‘gold mountain’. If they did not pay the money back, they would be threatened with violence by the lenders and would not be able to buy a ticket back to China.

Self-help organisations

When they arrived in California, many of the Chinese people spoke no English and did not know how to get to the goldfields. Organisations like the Sze Yup Society could meet them at the ship and assist them with accommodation and advice on how to set out for the diggings.

Members came from the four counties around the Pearl River Delta in southern Guangdong province and had a duty to protect and help one another.

Chinese camps at the diggings

Chinese miners tended to live in groups and work claims the other miners had abandoned. At first, miners were curious about the Chinese miners with their pigtails, conical hats and chopsticks.

But as the Chinese people became successful on the diggings, often working sections that the other miners had abandoned, white racist jealousies grew. White miners felt they deserved to be lucky and resented Chinese success, attacked Chinese camps and drove the people away.

Height of the Californian Gold Rush

In 1852, 67 000 gold miners arrived in California.

Of these, 20 000 were from southern China where there had been a serious crop failure. Americans became alarmed as the Chinese people continued to come through the port of San Francisco (on a single day, 2000 Chinese gold seekers arrived by ship). Previously there had been few Chinese people in the area. In 1851, there were about 2700 Chinese people living in California, but by the late 1850s Chinese immigrants made up 20% of the population in mining areas.

Discrimination, taxes and laws

While other miners physically attacked the Chinese people, the government introduced harsh laws and taxes. In 1850, California introduced a Foreign Miner’s Tax aimed especially at the Chinese people. It was $3 a month: about half of what the Chinese people were earning. They thus contributed large amounts to state finances. In 1870, the 48 000 Chinese supplied almost a quarter of the state’s revenue. In 1854, a legal judgement held that Chinese people and others deemed not to be ‘white’ could not testify against white people in court, meaning Chinese people became even more vulnerable to white murderous attacks.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 12.6

In 1862, California passed an Act ‘To Protect Free White Labor Against Competition with Chinese Coolie Labor’, although the legislation was not very successful in curbing Chinese immigration.

When the mines ran out

As the Californian mines ran out, some of the miners – including the Chinese people – went to Australia to the new gold rushes beginning there.

They called this the ‘new gold mountain’. In the United States, Chinese men moved into other occupations, including the laundry business, vegetable gardening, domestic service and later railway building. Some became a partner in a store in the mining areas that became very profitable, but many were employed on building the Central Pacific Railroad.

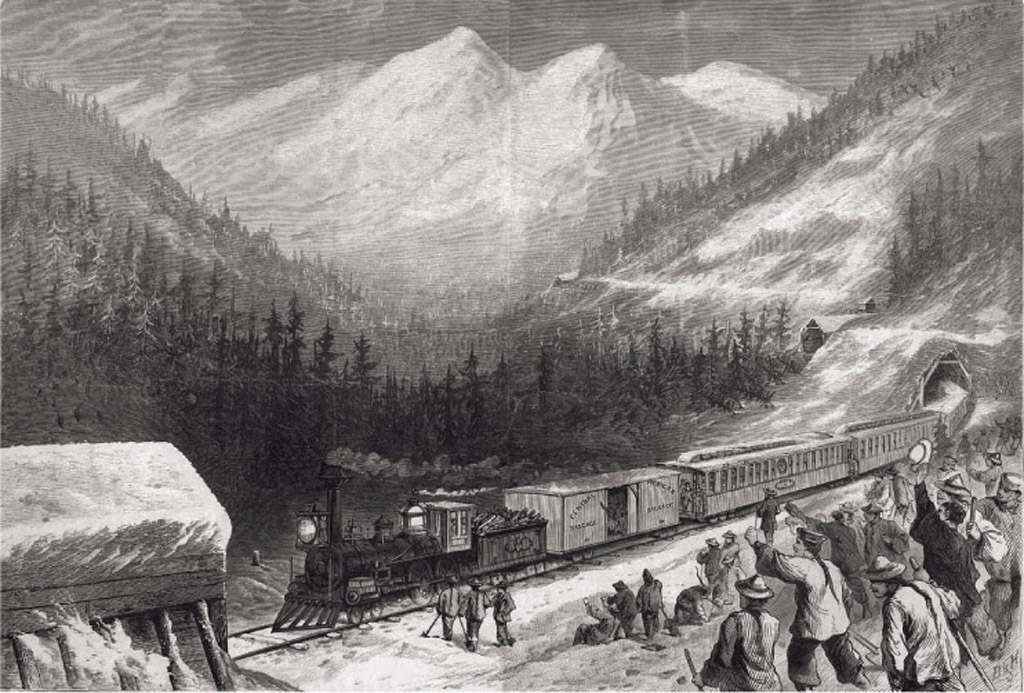

Rail tracks across the Sierra Nevada

From 1865, Chinese labourers worked on building the railway, which went up and across the steep and snowy Sierra Nevada mountains. This track was to join up the west coast of the United States with railways coming from the east.

This transcontinental railway was important to economic development. Thousands of Chinese people worked on the railway. The work was dangerous as they had to blast through the mountains: falling rocks, collapsing tunnels and snowdrifts killed many, and Chinese workers were also paid less than other workers. Finally, in May 1869, the Central Pacific met the Union Pacific in Utah and the transcontinental railway was open.

This was important in connecting national and world markets.

Chinese workers built other railways in the United States, but they were to suffer further discrimination when they were excluded from naturalisation as United States citizens in 1870.

Further, the entry of Chinese labourers and those employed in mining was prohibited by the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. One critic said this was the legalisation of racial discrimination.

Chinese workers were lowered in baskets down a cliff face to chip away at the granite where they would plant explosives to make way for the railway track. Sometimes the explosive would go off before they were pulled to safety.

Italians and Eastern Europeans to the United States

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Eastern Europeans and Italians went to the United States in large numbers. Many of them travelled in modern steamships. These were much larger than sailing ships and much more comfortable.

Journeys were shortened from 5 weeks to 2 weeks; eventually, Liverpool to New York took just 1 week. Refrigeration allowed food and water to be kept in more hygienic conditions, and the death rate on the Atlantic crossing dropped by 90%. The Inman Steamship Company introduced improved services for migrants, providing separate berths for each passenger, a women’s compartment, a ship’s doctor, three cooked meals a day, and soap and towels. Even though the fare was double that of a sailing ship, Inman dominated the British–American and Irish–American routes from the 1860s.

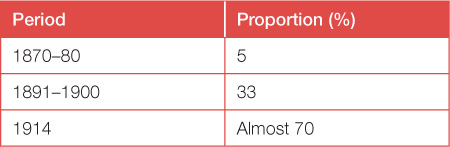

Migrants from Eastern Europe and Italy found their lives were greatly changed as they moved from agricultural to industrial settings. Many Americans were xenophobic and feared the arrival of what they saw as hordes of foreigners, whom they viewed as dirty, strange and likely to undermine their way of life. Nevertheless, these people made the United States more multicultural.

| Period | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|

| 1870–80 | 5 |

| 1891–1900 | 33 |

| 1914 | Almost 70 |

| Period | Number |

|---|---|

| 1871–80 | 70 000 |

| 1880–1900 | 250 000 |

| 1900–10 | 2 million + |

Migrants often wanted to escape poverty or religious and political oppression. They left high unemployment, rural backwardness and overpopulation to enter the vast new factories in Chicago, Detroit, Pittsburgh and New York.

They worked as manual labourers in meat works, coalmines, iron and steel production, construction and the textile and clothing industries. The fear of being conscripted into the Russian army drove many to America, as did the discrimination and persecution suffered by minority groups (especially Jewish people) at the hands of the Russian government. Anti-semitism was rife across Eastern Europe and Jewish communities had the bitter experience of pogroms, in which they were attacked, sometimes even by their neighbours. In America they felt they could be free.

Wonderful letters and amazing photographs

The first arrivals sent letters home to family members encouraging them to travel to the United States, a land of gold and freedom. They spoke of wages seven or even 10 times higher than at home and of the great freedom of American life.

Millions of letters, often with photographs of the migrants in new city clothes, made Polish and Russian peasants want to become Amerikanci too.

Migrants often sent money, known as remittances, home to help their families to survive or even to repair their homes. Migrants would arrange tickets for relatives, friends and sweethearts, so often these letters would also contain a ticket for travel to the United States and hopefully a life of prosperity and happiness. These letters formed a ‘chain’ to enable more migration. These people believed in the great legend that there was no poverty in the United States.

Italians

Between 1876 and 1914, more than 17 million Italians left their homes and migrated to other places in Europe and to the Americas in search of a better life. Most went to Britain, France and Germany, while many others sailed to South America. Between 1880 and 1920, more than 4 million Italians went to the United States. After farewelling family and friends they set off for the port with all their possessions. One woman recalled leaving: ‘We left in a two-wheeled cart that carried a big home-made trunk, my mother, two of my brothers, my sister and also a cousin from Palermo, which was forty miles away.’ Most of the migrants were male and of working age – between 15 and 45 years. Around 80% of these people were from the depressed rural regions in the south of Italy. Like so many regions from which migrants left at this time, this was an overpopulated and economically backward area.

These people dreamed of an easier life. ‘America’ was for them anywhere where they did not have to struggle so hard for a living.

They travelled in steerage class in the modern steamships, which plied the Naples–Philadelphia–New York route.

Little Italies

Most Italians who migrated to the United States were peasants; they often spoke only their Italian dialect and had little education. They had little experience of city life, but they usually settled into the poor crowded districts of the great American cities such as New York and Philadelphia. The districts were known as ‘Little Italies’ where people could speak to and get support from other migrants. They lived in tenement buildings, which were crowded, poorly heated in the winter and stuffy in the summer heat. On arrival, Italian men generally carried out unskilled and heavy jobs, such as building roads, bridges and subways.

Women worked at sewing and ran businesses selling Italian foodstuffs. They expected to make their fortunes in America, but many found that the streets weren’t paved with gold! Migrants often did the dirty jobs that no one else wanted to do, but slowly pulled themselves up into better positions in society and the labour market. They helped to build America. Many Italian–Americans told the joke: ‘First, the streets weren’t paved in gold; second, they weren’t paved at all; and third, we were expected to pave them!’

Hard-luck stories such as these disheartened many migrants, who then felt caught between wanting to stay and work at making a new and better life, and being pulled back to what they knew by returning to their homeland.

In Italian–American neighbourhoods, people organised a social life around their churches and celebrated religious feast days with processions and festivals. They organised concerts, theatre performances and social clubs, which helped them adapt to life in the United States.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 12.7

- Construct a list of the improved services that the Inman steamships offered to migrants crossing the Atlantic.

- Discuss why some Americans were hostile to the Southern and Eastern European migrants in the late nineteenth century.

- Explain why people left their homes in Eastern Europe and Italy and why they were attracted to the United States.

RESEARCH 12.1

‘Unsuitable immigrants’

As large numbers of Eastern Europeans and Italians arrived in the United States, some Americans began fearing the new migrants would change their society in unfamiliar ways. They found the new migrants strange, and decided that people who were not of Anglo-Saxon origin were inferior to them. Some developed ideas that people who were from north-western Europe – that is, Anglo-Saxons, Aryans and Teutons – were superior to what they called inferior races, such as Southern and Eastern Europeans and people from Asia and Africa. They felt these newcomers would change the social, political and economic wellbeing of the American nation. People like Francis A. Walker, a leading economist, journalist and educator, wanted their government to make laws to restrict the entry of such people. In 1896, he wrote: ‘The problems which so sternly confront us to-day are serious enough without being complicated and aggravated by the addition of some millions of Hungarians, Bohemians, Poles, south Italians, and Russian Jews.’

The 1880s, for a variety of reasons, saw an increase in strikes, unemployment, alcoholism, illiteracy, prostitution and crime. These problems more than likely would have occurred even if immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe had been excluded, simply because this period was a time of urbanisation, industrialisation and political corruption, and Americans were having a difficult time adjusting to the new social climate. However, many Americans were eager to blame migrants from south-eastern Europe as the culprits behind the new problems.