12.2c Era of mass migration: Indentured labourers

Indentured labour – a new form of slavery?

With the abolition of slavery in the British Empire in 1833, planters of sugar and other tropical crops were eager to get access to more cheap labour to toil on their great estates. Pressured by these planters, the British government devised a system of indentured labour to send Indians to work abroad. Under this system, the worker would sign on for 5 or 10 years to work for a low wage, after which the worker would be able to return home.

Many anti-slavery activists saw this system as just a perpetuation of slavery, especially as workers were often tricked into signing up and could be badly treated by their employers. Between 1834 and 1920, more than 1 million Indians were sent across the globe as workers. They helped develop the sugar and other industries and contributed to British wealth. Those who never returned to India helped to create new cultures in various corners of the world.

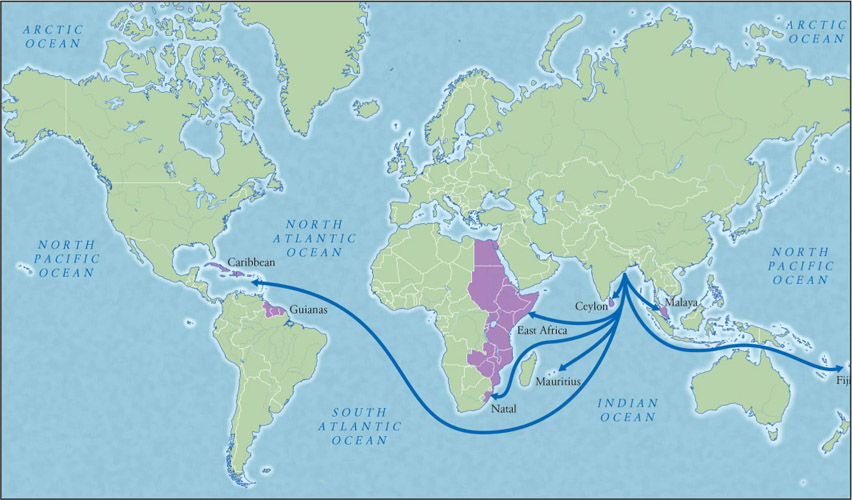

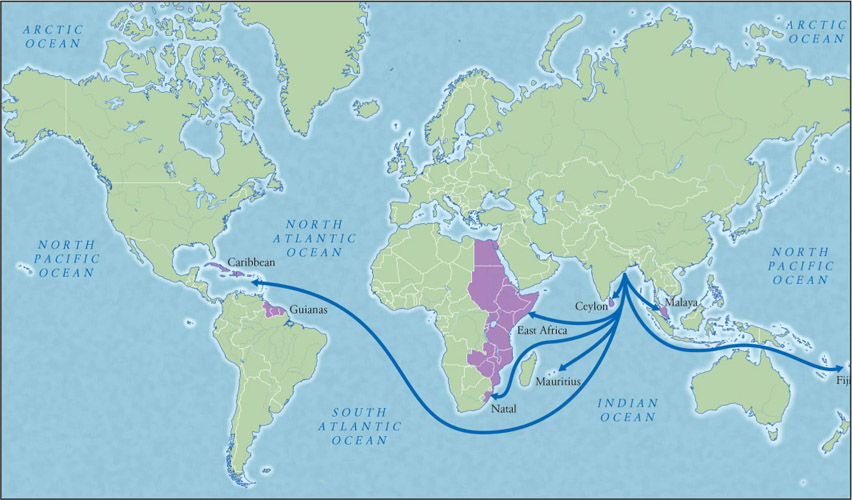

Where did they go?

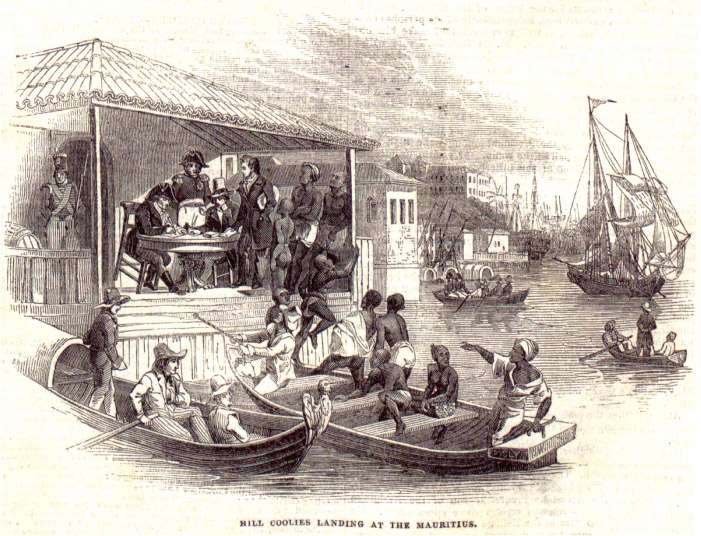

Almost 150 000 Indian workers were sent to Mauritius between 1834 and 1854. From 1844, Indians were taking the long journey of 20 weeks via the Cape of Good Hope and St Helena to Jamaica and other parts of the West Indies. In Natal, South Africa, the system of indentured labour began in 1860. Late in the nineteenth century, workers were being dispatched to Kenya in East Africa to build the Ugandan Railway.

They also went to German, Dutch and French colonies. This scheme went on for years and the last indentured labourers were sent to the West Indies in 1916.

Who were they?

The labourers, known then as coolies, were young, active and able-bodied people accustomed to performing hard labour.

Indians from all communities – Hindus, Muslims and Christians from high and low castes – were recruited.

Did these people have any choice about going?

Indentured labourers were from overcrowded agricultural districts beset by famine. Sometimes convicts and prostitutes were forcibly sent overseas by the authorities. Gullible and illiterate peasants were easily tricked by clever recruiting agents. Parts of India were hit by famine and many poor people agreed to do a job, but had no idea about where they were going or how long the voyage would take. They did not realise they would be away for 5 or 10 years.

Widows and abandoned wives were recruited and women were often kidnapped. Sometimes, however, recruits were happy to leave behind friction and trouble at home. In the novel Sea of Poppies, Amitav Ghosh describes the escape of Deeti, a widow. She was rescued from her husband’s funeral pyre, and joined the girmits going to Mauritius.

Bhagvana, a member of the low-caste ‘untouchables’, was very poor and his landlord would beat him every day. Due to her low status his mother was not able to go into the village temple. She cried, as she wanted to see the statue of Lord Ram, so Bhagvana took her inside. He was beaten by high caste villagers for offending them. He feared more beatings, ran away and registered to go to Fiji.

A regulated system?

The indentured labour system was more regulated than the slave trade.

The labourers had to testify before a magistrate that they understood the contract, and their health was checked before embarkation.

However, this system was frequently abused.

One recruit was told that if he did not say ‘yes’ to everything the magistrate asked, he would be put in jail. Little care was taken and this magistrate registered 165 people in only 20 minutes.

At each Indian port there was a Protector of Emigrants, who was to ensure that the ship was seaworthy and well fitted out. The workers were supposed to be supplied with all their dietary needs, including rice, dhal and chillies, as well as the medicines they might need on their long voyage. These regulations were designed to protect the emigrants, but could be evaded.

The voyage

The labourers had to endure very long voyages.

Sailing ships were still used to transport these recruits until early in the twentieth century. The West Indies trip could extend to 27 weeks. From Kolkata to Natal took 12 weeks, and it was 10 weeks to Mauritius. Workers had to endure crowded conditions and unfamiliar food. Even trivial acts of disobedience were punished by confinement. Still, they did have more freedom than the slaves who had been chained below decks. They could amuse themselves by playing drums, and sometimes they could watch singing and dancing concerts or wrestling displays. But the ships could be dangerous, and disease could spread quickly. In 1856–57, the average death rate for Indians travelling to the Caribbean was 17%. The Salsette, for example, left Kolkata in 1858 with 323 recruits, but 124 died en route and 13 were sent to hospital on arrival. Many died from diarrhoea, dysentery, cholera, measles and the adverse conditions of the voyage. Later a doctor was required to accompany each ship.

On arrival, workers were placed under the control of colonial officials and remained for about 1 week in the local depot before being sent to their new employer.

Abolition of the indenture system

Totaram Sanadhya was born in India in 1876. When he was a year old, his father died and his father’s assets were taken over by dishonest money lenders. When he was 17, he left home to look for work and met a man in a local market who told him about an easy, well-paid job. He was taken to Fiji.

Totaram worked as a bonded labourer in Fiji for 5 years, and was not afraid to uphold his rights. After finishing his indenture, he set himself up as a farmer and Hindu priest. He spent a lot of time helping others who were still indentured. He also campaigned to get Indian teachers and lawyers to migrate to Fiji, so they could also help the Indian workers, and enlisted help from Indian freedom fighters and missionaries. He returned to India in 1914 and wrote a book, My Twenty-one Years in the Fiji islands, about his experiences.

Totaram’s story was very important in informing Indian people about the lives of indentured workers. Early in the twentieth century, Indian people protested against the inhumanity of the system. They formed organisations to oppose this in India and also in places like Natal. They informed possible recruits, saying things like, ‘They take you overseas’, ‘They are not colonies but jails’ and ‘It is not service but deception’. In Natal, Gandhi organised one of his first campaigns around this issue and worked with GK Gokhale, the political reformer in India.

Totaram Sanadhya in Fiji also supported this work.

Gandhi sent Charles Freer Andrews to investigate conditions in Fiji. In 1917, indentured labour was abolished across the British Empire.

Fiji Indians today

The British government and the colonial planters in Fiji imported Indian labourers and used them to build their wealth. Descendants of Indians who remained there were well educated and prosperous in business. When Fiji became independent in 1970, 52% of the population were Fiji Indians.

Some indigenous Fijians feel they are on the margins of their country and resent the success and the authority of Fiji Indians. Life in Fiji has become very difficult for Fiji Indians, with military coups in 1987 and in 2000 against democratically elected governments led by Fiji Indians. These coups were supported by some indigenous Fijians. Now the descendants of the girmits see no future for themselves in Fiji. Many have left, with about 50 000 resettling in Australia. They see themselves as ‘twice banished’.