12.2b Era of mass migration: Convicts

Transportation of convicts to Australia

In 1788, the British established the colony of New South Wales at Botany Bay. This was a convict or penal settlement and the 759 convicts and their jailers were the first non-Indigenous settlers of the southern continent. In all, 162 000 convicts were sent to Australia by the British government between 1788 and 1868. Prisons in England were overpopulated and those not belonging to the middle or upper classes were often unable to survive due to a lack of employment opportunities that arose out of the Industrial Revolution. Only 15% of the convicts were women. In 1804, convicts were sent to Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania) and later to Victoria, Queensland and Western Australia.

The convict system was the basis of British colonisation of Australia and changed the lives of Australian Indigenous peoples. Transportation halfway around the world also had a great impact upon the lives of the individual convicts. For some it led to a life of misery, and even resulted in death, and for others it led to a more comfortable and happy life than they could have had in Britain.

The settlement led to the taking of Indigenous land. With the convicts, soldiers and settlers came diseases to which Indigenous people had no defence – including typhoid, influenza and smallpox – and which caused many deaths. Many other Indigenous people were killed in brutal clashes with the military, convicts and explorers.

The next hundred years saw Indigenous peoples thrust out of their country, driven out of habitable land, and shot, poisoned and massacred as British settlers claimed land for building, agriculture, grazing and mining.

Who were the convicts?

Most convicts were from England and Wales, with about a quarter from Ireland. Many of the convicts were young urban people who were convicted of theft and were sentenced to 7 or 14 years’ transportation to Botany Bay. For stealing a coat, you had to leave home and your family, perhaps forever. Before going to Australia, prisoners were kept on old ships, or hulks. There, some made a keepsake or love token for those they were leaving behind. On a coin, one person engraved the message, ‘Dear Wife When you this see remember mee [sic] When I am far away from the[e] John 1836’.

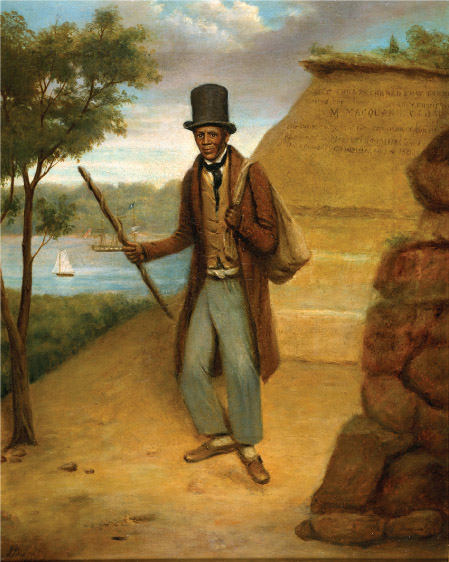

Not all the convicts were English, Welsh or Irish. Around 800 convicts were of African or Indian descent. Australia’s first bushranger, Black Caesar (1764–96), was probably born a slave in the American colonies, leaving with the British forces that freed him. But he was sentenced in Kent in 1786 and arrived in New South Wales with the First Fleet on the convict ship Alexander in January 1788.

Convict ships

Convicts made the long journey to Australia confined for up to 159 days in small ships such as the Surry which was only 36 metres long and 9 metres wide. The voyage was a strange experience for convicts who had not been at sea before. Most were angry and sad at leaving family and home, but a few were happy to join relatives or sweethearts already transported.

Convicts were usually allowed on deck for short periods. However, the conditions on the Second Fleet, which arrived in 1790, were terrible. The ships were damp and disease raged among the prisoners, who were confined below decks. Many were not given enough food, and 247 men and 11 women died before the ships finally arrived at Sydney. Most of the remaining passengers were very sick on arrival.

Government regulations required that prisoners should be fed adequately and allowed to exercise on the deck, and that they and the ship should be cleaned and fumigated regularly. Where officers were negligent and careless, standards were inferior. Ships stopped for more provisions at Rio de Janeiro or the Cape of Good Hope. The sight of land must have been welcome, but prisoners were not allowed ashore.

After 1815, naval surgeons were appointed to each ship, and on well-organised ships conditions were better. Naval surgeons refused to take sick, frail and elderly prisoners who could not stand the rigours of the trip. Surgeons’ pay and return passage were dependent on the delivery of healthy convicts. Prisoners were divided into groups to receive rations and do their own cooking. Many prisoners ate better and more regularly than before their imprisonment. The weekly rations for the women prisoners on the Princess Royal in 1829 included beef, pork or plum pudding for dinner each day, pea soup several times, a pot of gruel with butter and sugar for breakfast, 350 grams of biscuit each day, and tea and sugar. Lime juice and red wine were given to combat scurvy.

These women were allowed on deck from time to time.

Discipline was strict and harsh on all convict ships. Where mutiny was threatened or prisoners were disobedient, they could be chained and flogged. Where male and female convicts were transported on the same ship, many formed sexual relationships and women could arrive pregnant in the colony. After 1829, male and female prisoners sailed on separate ships.

Sometimes female prisoners formed relationships with sailors. Often there was no protection for female prisoners from sailors who forced their attention on them. Some women convicts formed relationships with sailors because they could provide them with rum or extra provisions.

Sometimes they had families with these sailors when they settled in the colonies.

Work and punishment in the colonies

Convict labour was used to establish colonies in Australia. Shortly after arrival they would be assigned to an employer. They might work on a farm under the orders of the farmer and receive food, clothing and accommodation. They also worked for the government – for example, making bricks and building roads and harbours. Women might do farm work or house work. If they failed to follow orders or stole, they might receive further punishment. Women could be punished by having their heads shaved. Sometimes women were flogged. In 1791, Lieutenant Ralph Clark ordered Catherine White and Mary Higgins to be flogged 50 times. After 15 strokes, Catherine fainted and the doctor said she should have no more. Mary Higgins was flogged 26 times, but Clark excused her from the rest because she was an old woman.

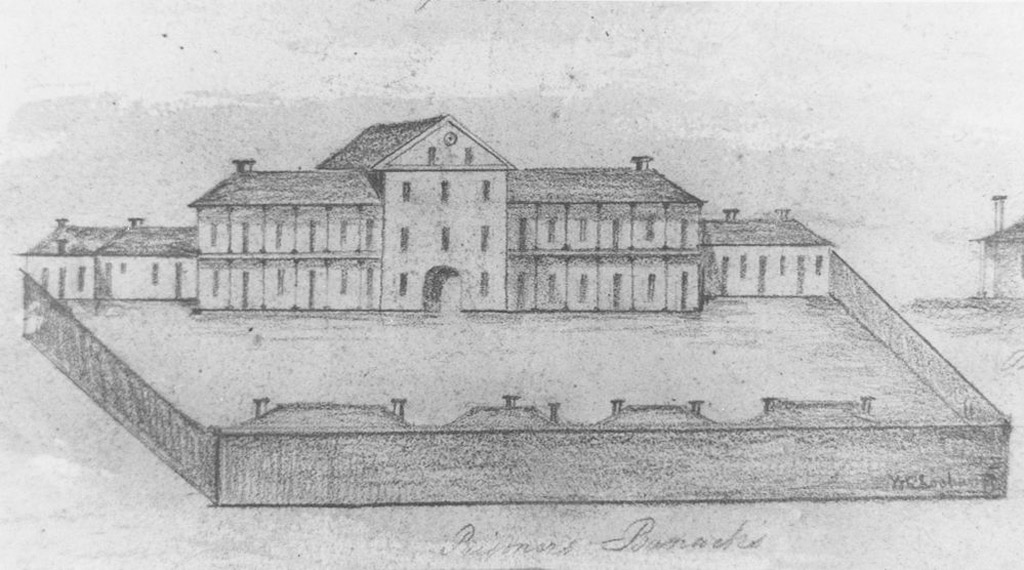

Women who committed a crime also could be sent to the Female Factory in Parramatta, which was like a prison. Convict women were also sent there to have their babies. On arrival, women were often sent directly to the Female Factory where they worked all day and lived communally at night in sparse surroundings. Later, they might be employed as domestics and taken from the factory to live as a mistress or even marry and raise a family with a settler. There was no sentence to serve; instead they were taken as needed to work by the male population.

Male convicts could receive severe floggings.

Alexander Harris witnessed this at Bathurst Court House in the 1820s: ‘I had to go past the triangles, where they had been flogging incessantly for hours. The scourger’s foot had worn a deep hole in the ground by the violence with which he whirled himself round on it to strike the quivering and wealed back, out of which stuck the sinews, white, ragged and swollen … I know of several poor creatures who had been entirely crippled for life by these merciless floggings.’ Indigenous people were disgusted at the intracultural violence, which could be described as savage, barbaric and primitive.

Secondary punishment

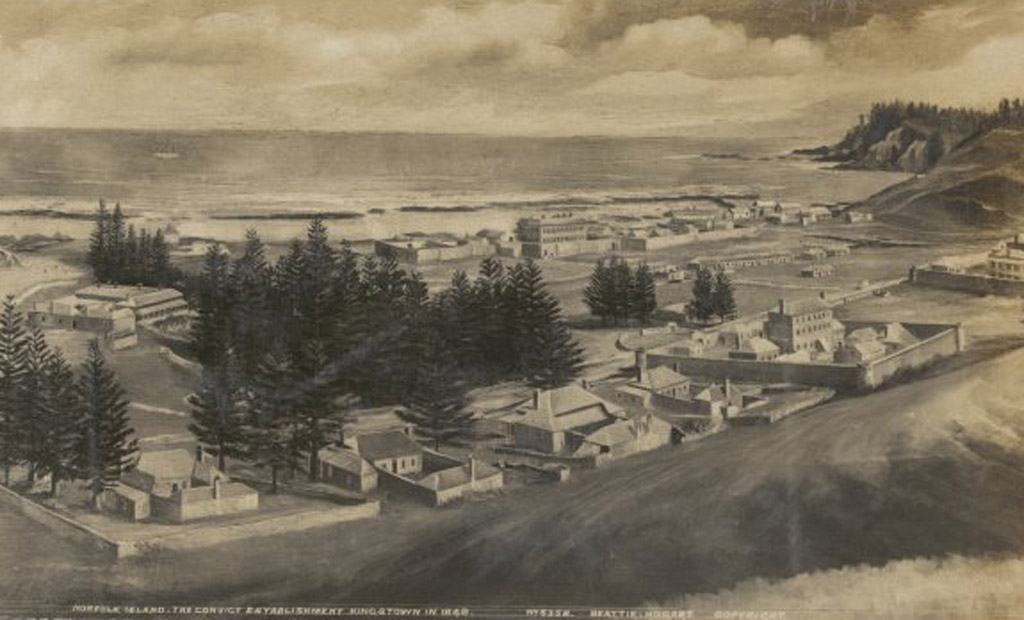

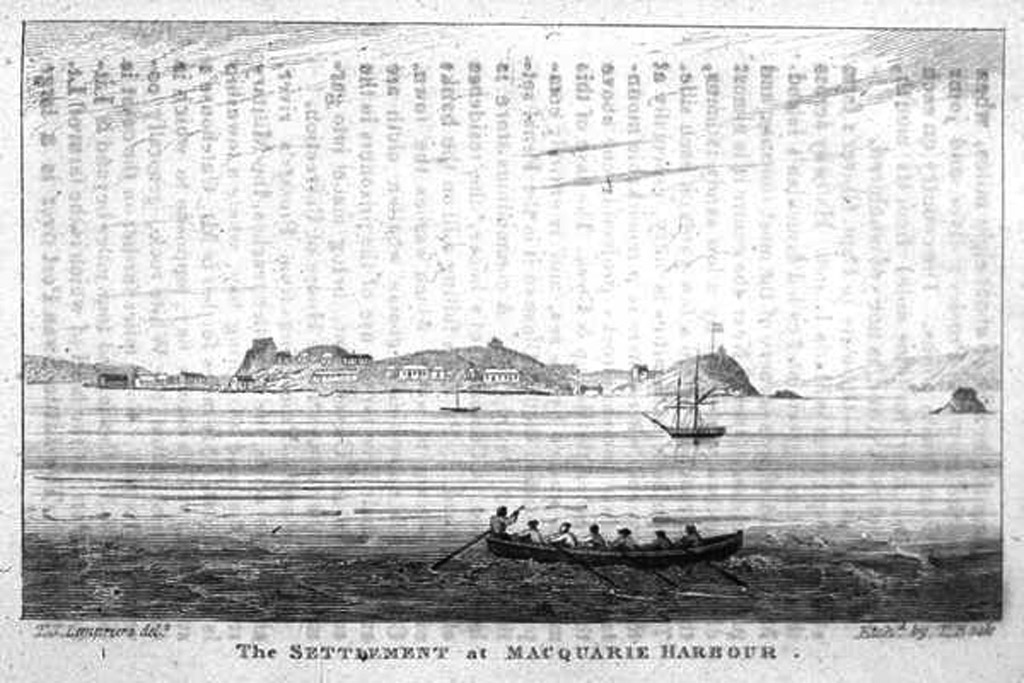

Male convicts who re-offended could be sent to a place of secondary punishment such as Norfolk Island, Newcastle, Macquarie Harbour or Moreton Bay. One of the worst places was at Macquarie Harbour in southwest Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania), where the narrow entrance to the harbour was known as ‘Hell’s Gates’. The punishments were severe and a cat-o’-nine-tails (see Source 12.8) was used to flog the prisoners.

One of the most frequently flogged prisoners was Thomas Brookes, a convict at Port Jackson, Newcastle and Moreton Bay. He received eight separate whippings – a total of 1025 strokes – upon his body. He said, ‘They were not comfortable to take’.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 12.4

Convict records

Most convicts were not locked up but rather lived and worked in the colonies for private employers or for the government. From time to time a convict muster was held in order to find out where they all were. All this information was written down in large books. The authorities kept very good records about the convicts, including details of height, colouring and distinctive scars and tattoos.

Recently historians have used these detailed records to find out more about the convicts. We now know that the women convicts had many useful skills as general servants, cooks, launderers, kitchen hands, needle workers and house maids.

These skills were valuable in the new colony.

Almost one-third of these women could read and write, and many who could not write could read. Until the 1970s, many Australians were embarrassed about having convict ancestors, but now people are more eager to find out about their forebears through these records.

Babette Smith was able to find out about the experiences of her ancestor, Susannah Watson.

Experiences included marriage, losing a child, and being arrested for shoplifting.

Smith also found letters Susannah sent back to England. She wrote to her daughter Mary Ann in 1868, when she had been almost 40 years in Australia (see Source 12.9).

My dear and affectionate daughter, I received your ever welcome and affectionate letter and indeed I cannot tell you how glad I was to hear from one of my dear children so many thousands of miles away from me. Dear Daughter, you cannot tell what happiness it gave me to receive your likeness. To think that I should live to gaze upon that dear face again, although so altered since I parted from you all.

Source 12.9 In B. Smith, A Cargo of Women, UNSW Press, 1988, pp. 155–6

A tattoo was a way in which convicts could remember their loved ones in Britain. Eleanor Swift had a tattoo: ‘Patrick Flinn I love to the heart.’ Signs had particular meaning; for example, an anchor signified hope and constancy. But such personal statements could also be used to identify runaway convicts. It was difficult for convicts to escape, as each penal colony was virtually a prison, but some tried to escape by crossing the Blue Mountains, or stealing a boat and sailing to Java.

Others stowed away on ships leaving for Kolkata or went and lived among Indigenous people.

There are accounts of positive interactions between convicts and Indigenous people, including escaped convicts living within or being helped by Indigenous communities. An example of this is the story of William Buckley, who met with a group of Wathaurung women several months after his escape. He was given the name Murrangurk, which literally meant ‘returned from the dead’.

Emancipists

When convicts finished their sentence, some people still saw them as disgraced. But Lachlan Macquarie, Governor of New South Wales in 1810–1821, believed these emancipists should be socially accepted. He said: ‘Some of the Most Meritorious Men of the few to be found, and who were Most Capable and Most willing to Exert themselves in the Public Service, were Men who had been Convicts!’

Many became more prosperous than they ever could have dreamed when they left Britain in chains. Simeon Lord, transported for 7 years for theft, became a wealthy merchant, international trader and a pastoralist. He became a magistrate and regularly dined at Government House. Mary Reibey was transported for stealing a horse when she was only 13 years old. She became a wealthy businesswoman.