12.2a Era of mass migration: Slaves

Types of migration

The period 1750–1901 was one of great diasporas, as people moved across the globe.

Enslaved people were taken from Africa to the Americas, North and South, and the Caribbean islands.

Millions of Indians migrated as indentured labourers, agreeing to work with the right of return and freedom after some years. Many were free settlers who chose when and where to migrate and could travel in relative comfort. But many seen as free settlers had no real choice and left lives of poverty and hardship, political oppression or religious persecution for the hope of a better life. On arrival, many had to repay all or part of their fares from their earnings before they could start to build new lives.

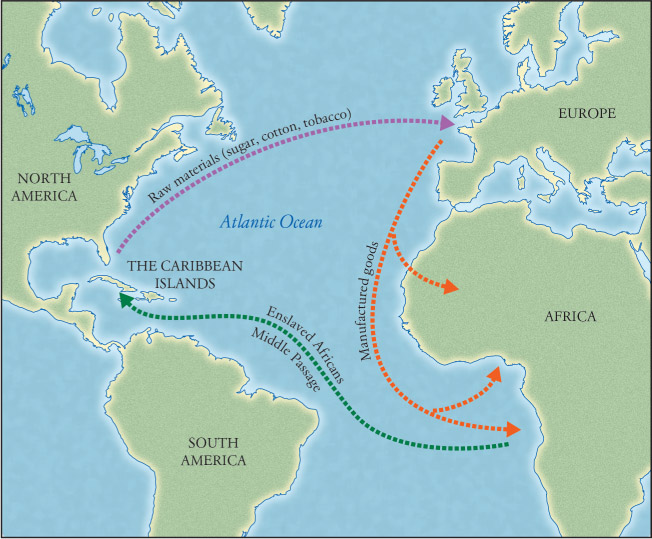

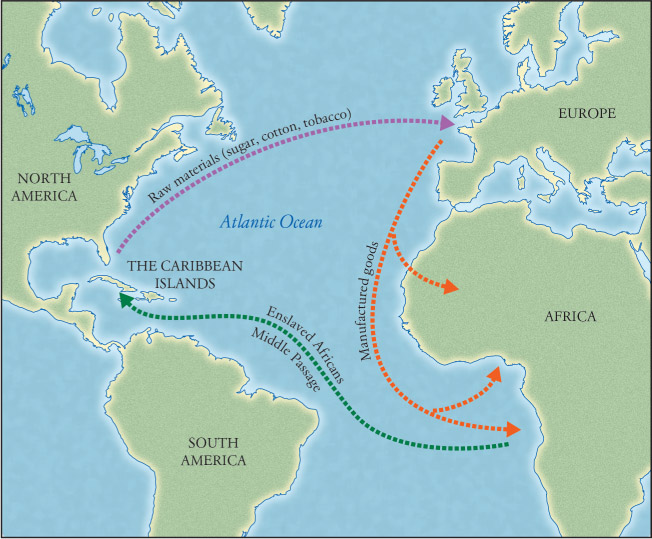

The Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade saw millions of Africans enslaved and shipped to a life of servitude in North and South America (the Americas). It began in the sixteenth century and continued until the mid-nineteenth century. In the eighteenth century about 6 million Africans were enslaved, along with another 4 million during the nineteenth century. The trade was part of a triangle of capitalist shipping around the Atlantic. Manufactured goods such as guns and textiles were shipped to the west coast of Africa and traded for slaves. The slaves were loaded into ships and sent across the Atlantic to provide labour for plantations in the Caribbean and the Americas. These plantations produced sugar, cotton, tobacco, rice, indigo and coffee. In turn these raw materials, particularly cotton and sugar, were taken to Western Europe for refining, manufacture and consumption, and then sent on via the trade triangle to Africa.

Capture

Slavery was long established in Africa. Slaves were commonly taken to Arab countries, and from the midfifteenth century to Portugal and other parts of Europe. But the huge demand for labour in the Americas in the eighteenth century intensified African slavery and changed it to a harsher and more brutal system. Africans were captured by other Africans, chained and forced to walk many kilometres to the coast, where they were branded with hot irons and imprisoned in forts before leaving for America. Many died after capture and in the forts. Strong and healthy young people were valuable to the slavers as they could have a long working life ahead of them.

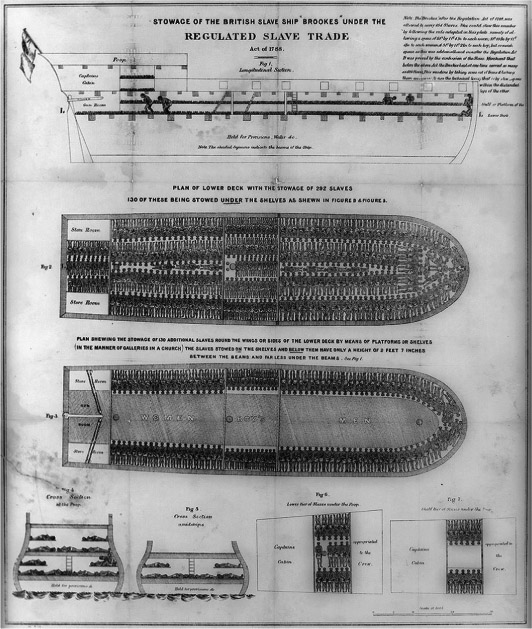

The Middle Passage

Slaves were crowded onto slave ships where they were chained and made to lie on their backs.

The trip across the Atlantic Ocean was long and dangerous. Conditions were often filthy and when disease spread among the slaves, the living could stay chained to the dead for days on end. There was a high mortality rate on these voyages and the sick could be thrown overboard to stop the disease spreading among the other slaves. Those who survived this horrific journey were then prepared for sale. They were washed and shaved and sometimes oil was put on their skin to make them appear healthy.

Some treated the slaves better, but only to attract a higher price for them at sale.

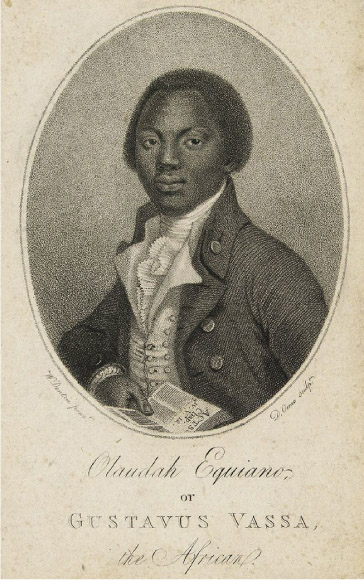

Olaudah Equiano was born in 1745 in a village in what is now Nigeria. At 11 years of age he was captured and sold into slavery, ending up on the Caribbean island of Barbados. He managed to buy his own freedom when he was aged about 21 years and then worked as a writer, merchant and explorer in the Caribbean, South America, the Arctic, the American colonies and in Great Britain. In Britain he was a popular speaker about the evils of slavery. His autobiography The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, of Gustavas Vassa, the African (1789) was important in converting people to the antislavery movement. In later life he worked for the good of African people.

Equiano recalled that when he arrived in the West Indies, ‘many merchants and planters came on board and examined us. We were then taken to the merchant’s yard, where we were all pent up together like sheep in a fold. On a signal the buyers rushed forward and chose those slaves they liked best’.

Working lives

Sugar plantations needed lots of labourers to do heavy manual work: clearing the forests, planting, harvesting cane and processing the sugar. Field labourers had the hardest jobs and could work 18 hours a day, 6 days a week in the fields, watched by the slave driver. Children and pregnant women worked at hoeing, weeding and carrying water. In Brazil they were on the coffee plantations, while in Peru slaves worked as miners. House slaves lived in the master’s or mistress’ house and were on duty all day and night; they would cook, clean and look after children.

Chattel slaves

Slaves had no rights; they had become things or chattels owned by others. They could not even keep their family with them. They and their children could be sold or given away. Mary Prince was born into an enslaved family in Bermuda in about 1788. When she was aged 12, she and her sisters were sold.

The sale master:

took me by the hand, and led me out into the middle of the street, and, turning me slowly round, exposed me to the view of those who attended the sale. I was soon surrounded by strange men, who examined and handled me in the same manner that a butcher would a calf or a lamb he was about to purchase. The bidding started at a few pounds, and gradually rose to 57.

The people who stood by said that I had fetched a great sum for so young a slave. I then saw my sisters led forth, and sold to different owners.

When the sale was over, my mother hugged and kissed us, and mourned over us, begging us to keep a good heart. It was a sad parting; one went one way, one another.

Punishment

Her new owner made Mary Prince work in the house and the fields, and she was often flogged: ‘To strip me naked – to hang me up by the wrists and lay my flesh open with the cow-skin, was an ordinary punishment for even a slight offence.’ Slave owners severely punished any slaves who were disobedient, careless or tried to escape.

Those suspected of plotting a revolt were treated brutally. This is how the slave owners kept control.

Abolition of slavery

Slaves had always resisted their condition and had revolted against their owners from time to time. In 1804, slaves in the French colony of Saint Dominigue rebelled and set up the republic of Haiti, the first black republic in the world. The Haitian rebellion stands out in history because it achieved permanent independence for its enslaved peoples. In Britain and the United States, former slaves wrote and spoke about their experiences. These included Mary Prince, Ottobah Cugoano and Olaudah Equiano. Their publications and their activism in anti-slavery organisations, such as the Sons of Africa, were important in changing public opinion.

In the United States, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s bestselling novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, published in 1852, was an important tool for the abolitionists.

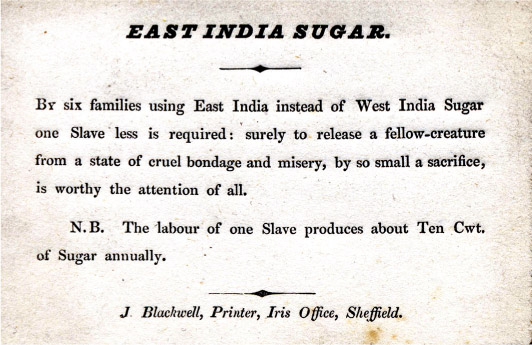

Antislavery activists campaigned against the sugar that slave owners sold. James Wright, an English Quaker, announced in 1791 that he would sell no sugar grown by slaves.

Quakers, Unitarians and some other Christians argued that slavery was immoral.

William Wilberforce told the British parliament in 1789 that they were all responsible for slavery: ‘I mean to take the shame upon myself, in common indeed with the whole Parliament of Great Britain, for having suffered this horrid trade to be carried on under their authority. We are all guilty – we ought all to plead guilty.’ Women formed antislavery societies, putting anti-slavery slogans on their handbags and mottos on their sugar bowls such as ‘sugar not made by slaves’. This led to boycotts of slave-grown sugar.

Although many Europeans and Americans profited from slavery, gradually public opinion turned against slavery. Industry and changes in the economy were most important. Slavery was seen as no longer profitable; free and more mobile labour was required. The British government abolished the slave trade in 1807, but slavery itself was only abolished in the British Empire in 1833. Other powers like France (1818), the Ottoman Empire (1847) and the United States (1865) abolished slavery at various dates.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 12.2

Costs and benefits

Slavery debased all involved: those who were sold and brutalised, and those who owned the slaves and whipped them. Africa lost millions of young and strong people over the centuries. This affected the economic growth and development of the continent and the standards of living of the African peoples. African slavers also benefited from selling slaves.

The New World of the Americas benefited greatly from the supply of free labour. The slaves cleared forests and jungles, developed agriculture and worked to process raw materials in sugar mills, tobacco mills and cotton factories. These were particularly fruitful crops in the southern United States, but required back-breaking work, which allowed the slave trade to thrive. The clearing of the land helped to destroy the way of life of Native Americans.

In Britain and Europe, factory owners acquired a good supply of raw materials and bankers’ profits grew as they financed the building of new ships and factories. Ship-owners could make a profit of 20–50% on supplying and selling slaves, and ports such as Bristol, Liverpool and Lisbon prospered on the slave trade. Ordinary people could afford to buy sugar and cheap cotton clothing.

The 200th anniversary of the abolition of the British slave trade in 1807 was celebrated in 2007, and prompted historians to research the economic benefits of centuries of slave labour to countries like Britain and the United States. They are coming to understand how it has contributed to the dominance and power of Western countries.

To remember the slaves’ suffering, some people have organised pilgrimages and processions.

Source 12.5a In 2007, the International Slavery Museum opened in Liverpool, UK (01:46)

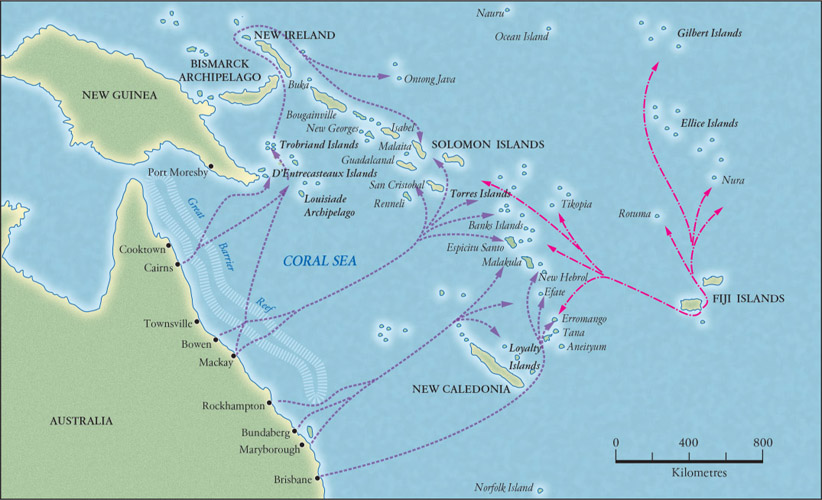

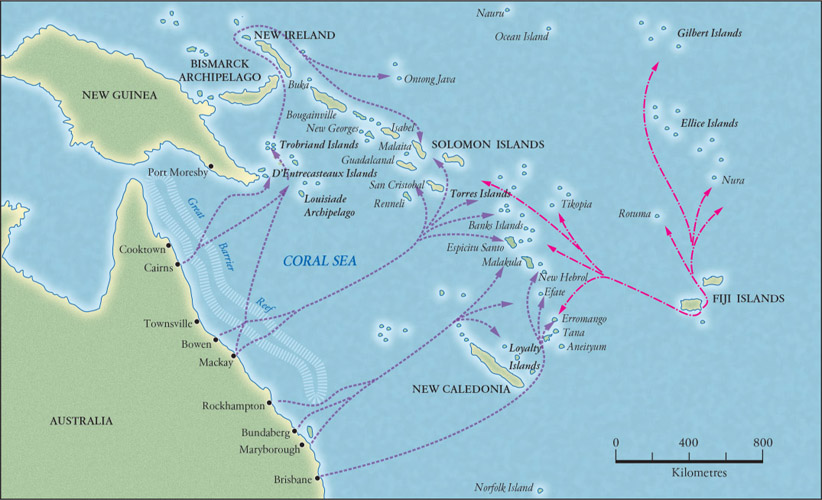

Queensland slave trade

Even though slavery was abolished in the British Empire in the 1830s, people were still being captured and enslaved. In the early 1860s, Polynesians in the eastern and central Pacific were captured and taken to Peru to work in the guano mines. During the 1860s, there was a demand for cheap labour for plantations in the colonies of Fiji and Queensland. Ship captains could profit from capturing South Sea Islanders, especially young men, and taking them to Fiji and Queensland to sell them to sugar planters. Their ships operated in Melanesian waters, around the New Hebrides and Solomon Islands. This was termed ‘blackbirding’.

From 1863 to 1875, about 10 500 islanders were kidnapped and taken to work in Queensland.

How were islanders kidnapped?

The ‘blackbirders’ used force and trickery to get the islanders on board their ships. Islanders were often curious about the ships that appeared off the coast, and paddled canoes out to see the ship and to sell fruit and fresh fish. European sailors would smash or sink their canoes and take the islanders on board, or they might entice them with beads and axes. Sometimes sailors would show islanders over their ship and, once they were in the hold, lock them in. Where people had been visited by missionaries, they were sometimes tricked to come out to the ship with news that there was a bishop on board. Raiding parties would go ashore and take people from the beaches or near their villages. When people tried to defend themselves and escape, the superior firepower of guns usually won out. On a few occasions, when ships came later on, some islanders tricked the recruiters by enticing them away from the shore and then attacking them with guns. In 1883, Captain Belbin of the Borough Belle was murdered on Ambrym (today part of Vanuatu) by islanders angry about the kidnapping of a young boy.

Dangers of the voyage

Once imprisoned in the hold, the terrified islanders had no idea where they were going. It was 1600 kilometres to Queensland. They could not speak the English of their captors nor the languages of captives from other islands. The food on board was strange and the drinking water might be foul.

Some captives were injured and others became sick. The dead were just thrown over the side.

The recruiters were greedy and brutal. In 1871, James Patrick Murray, a Victorian doctor and owner of the brig Carl, and the ship’s Captain Armstrong captured people from different islands.

When these men began to fight and tried to set the boat on fire, Murray fired into the hold, killing 60 islanders and injuring others. The dead and wounded were thrown overboard. When news of this voyage became widely known, Captain Armstrong and some crew were put on trial.

Armstrong was sentenced to death, which was decreased to penal servitude for life. Murray escaped prosecution by presenting as a witness against his own employees.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 12.3

Arriving in Queensland

In Queensland, the islanders were sold to planters and forced to work long hours in the cane fields.

They had to learn English and get used to different foods. Those who worked for pastoralists inland struggled to cope with the different climate, especially the cold nights. They had no way of contacting their families and had to try to survive in an alien place.

Being indentured

From the mid-1870s, the Queensland slave trade of Pacific Islanders was replaced by a more regulated system of indenture, where islanders agreed to work in Australia for a fixed period of time. Many people argued that it continued some of the worst features of slavery. Some Queenslanders, whose grandparents were indentured, have stories of their capture that are stories of kidnapping. Between 1859 and 1900, more than 100 000 Pacific Islanders were recruited. Most (62 500) went to Queensland, and others went throughout the Pacific Ocean to Fiji, New Caledonia, Tahiti, Samoa and Hawaii, while about 5000 went to Peru and Guatemala in South America. Unlike slaves, indentured workers were free once their period of indenture had ended and their children were born free. Indentured workers were supposed to be able to return to their homes at the end of their contract.