11.2 Population movement and settlement

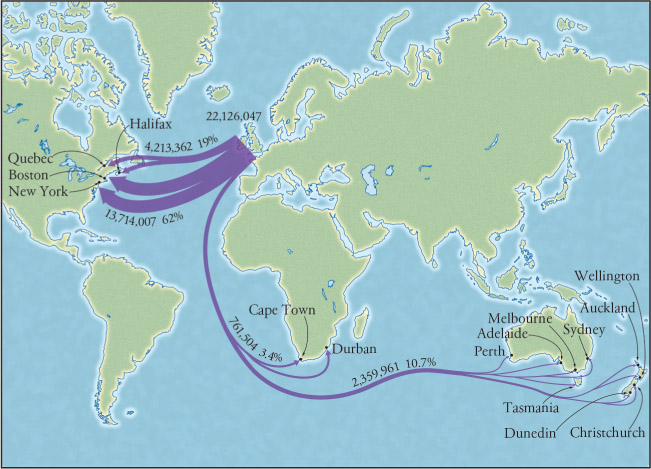

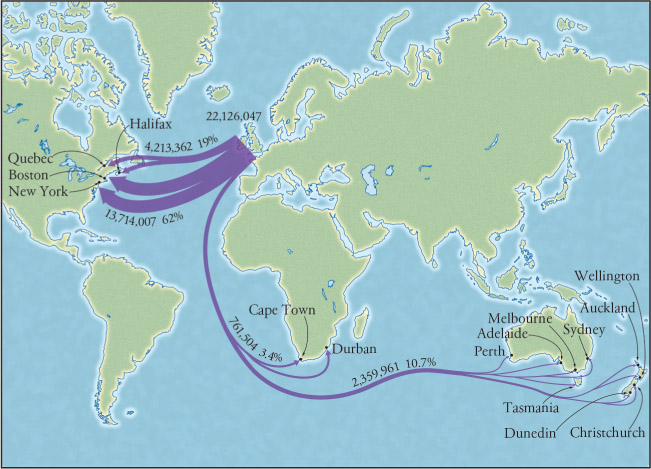

The Industrial Revolution caused whole populations to move across the world. Emigration from Britain began almost as soon as it gained its colonies. By the nineteenth century, British citizens could consider going to Australia, the United States, British North America (Canada), India, South Africa and New Zealand. By the 1840s and 1850s, the flood of migrants was so great that it caused public debate and concern in the government. The United States was originally the most popular destination: in 1849, 219 450 people went to America, while only 32 091 chose Australia and New Zealand. Later, more migrants chose to go to Australia, partly because the transportation of convicts was ended (1840 in New South Wales; 1853 in Tasmania) and partly because gold was discovered in 1851.

By the 1840s, it was clear that the Industrial Revolution brought wealth only to the middle classes and to the businessmen who owned the great factories. In 1841–42, a harsh winter caused unemployment and hunger for the working classes. In 1846, the Irish Potato Famine began.

Thousands of starving Irish people flooded to England, America and to the colonies in search of work. In 1848, there was a cholera epidemic that killed thousands more people. After 1851, the clearance of poor agricultural workers from the Scottish highlands drove many Scottish people to migrate as well. There was no hiding it: the Industrial Revolution had brought misery to working people. Among educated people, there was real concern about ‘the condition of England’.

From the early nineteenth century onwards, British people were encouraged to go to the colonies in Australia, where there was the promise of cheap farming land and a decent living.

The Industrial Revolution transforms the way of life in Australia

The Industrial Revolution wasn’t limited to just England: it gradually transformed Europe, America and Australia. We can still see its effects in the cities, towns and country areas we live in. There is also much visual evidence of early industry in hundreds of photographs and engravings.

The Industrial Revolution began to affect Australia as early as the eighteenth century. This was partly because England’s industrial cities, with their problems of unemployment and poor housing, turned many ordinary people into criminals, often for crimes as minor as stealing a loaf of bread to feed their families. The loss of the 13 American colonies in 1783 in the American War of Independence meant that the British could no longer send prisoners there. With Britain’s jails overflowing, the government decided to use Australia as a penal colony. Cities such as Sydney and Hobart came into existence to contain the social problems caused by the Industrial Revolution.

While the idea of setting up a vast prison was an important reason for settlement in Australia, it was not the only one.

From an early stage, the British government had wondered whether Australia could also serve as a settler colony; that is, a place to which people who were not criminals could freely go and start a new life by setting up farms and industries. The first free settlers arrived in Australia as early as 1793, and 1000 had arrived by 1810. The small settlement in Australia also gained settlers by giving grants of land to people who were already there and serving as officers in the army.

People such as John and Elizabeth Macarthur proved to be very capable settlers, and both were important in setting up Australia’s wool industry, which would soon become a major part of Britain’s trade with its empire. In 1823, the idea of settlement was helped by the Bigge Reports, which said that Australia needed more free settlers.

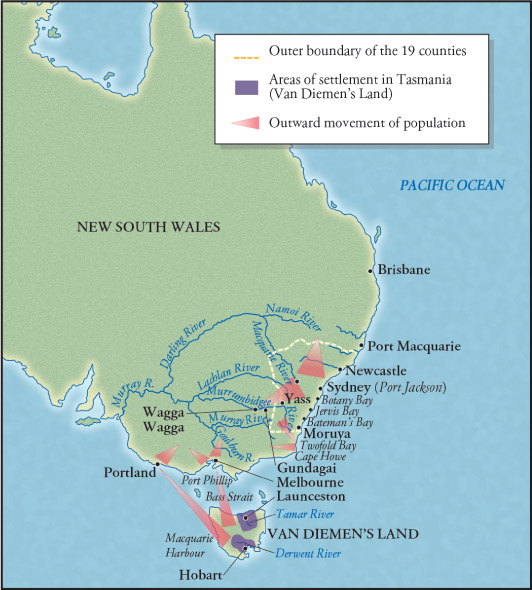

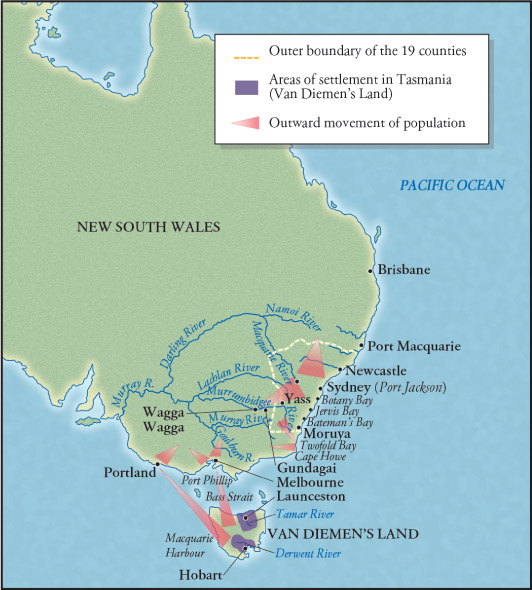

In 1831, the British government arranged to help settlers emigrate by paying the cost of the journey, using money from the sale of government-owned land. Later, the British government encouraged women to emigrate to help balance the numbers of males and females, and about 3000 arrived between 1832 and 1836. By the 1830s, there were large areas of the south-east coast of Australia under settlement (see Source 11.17).

There were two other events that helped the settlement of Australia. In 1840, the transportation of criminals to Sydney was halted, helping to soothe people’s fears that Sydney was just a prison. The last colony to stop transportation of criminals was Western Australia, which ended the practice in 1868. During the 1830s and 1840s, pastoralists (settlers who wanted to set up farms) began settling land in the areas now known as New South Wales and Tasmania. In 1835, some pastoralists from Tasmania also set up farms in what they called the Port Phillip District, which was renamed the colony of Victoria in 1850.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 11.7

- Explain why the rate of migration to Australia increased in the second half of the nineteenth century.

- Research the Scottish highland clearances on the internet or in the library. Why were these poor agricultural workers cleared from the land?

- Describe some of the differences between a settler colony and a penal colony. What are some of the similarities?

Elsewhere, people had other reasons for making settlements. In 1834 the British parliament had established the colony of South Australia to create a settlement free of convicts. In 1829, a group of settlers had joined together to form the Swan River Settlement in Western Australia, in order to create a new society and way of life. Finally, the great movement of settlers out of New South Wales to land in the north broke away from the home colony in 1859, and formed the colony of Queensland.

During the 1840s, 15 000 people migrated to Australia each year, reaching the peak of 33 000 in 1841. By the 1850s, it was clear that Australia could indeed be another ‘new Europe’, and serve as a useful settler colony to the British Empire.

As early as 1821, Australia was sending 175 000 pounds weight of wool (almost 80 000 kilograms) to Britain, but by 1850 this had risen to 39 000 000 pounds (17 690 tonnes). Australia alone was supplying about 50% of Britain’s needs in wool.

The discovery of gold in Victoria in the 1850s also provided great encouragement to migration.

The gold rushes of the 1850s had a dramatic effect on Australia’s industrial development. First, the population of the colonies grew from 500 000 in 1850 to 1.2 million in 1860. Second, the new wealth created by gold created more demand for products, leading to a rapid growth in Australia’s industry. The effects of this were still felt in the economy as late as the 1880s. Third, between 1860 and 1890, economic growth was also fed by strong migration from Britain and Ireland, which created one-third of all population growth in this period.

Finally, Australian governments borrowed heavily from Britain in order to build the services such as transport that Australians were demanding.

British investors were keen, until the 1890s, to invest their money in Australia, which they felt was a familiar culture and one made ‘safe’ by the wealth created by gold.

Transformation of Australia’s cities

Australia’s cities grew quickly during the nineteenth century, especially after the gold rushes of the 1850s. Melbourne was perhaps the main boom city of the nineteenth century, growing from a population of 30 000 in 1850 to 500 000 by 1900.

Sydney reached the same population by the end of the century. Adelaide was smaller, but still grew to 160 000 by 1900. Both Brisbane and Perth grew more slowly, but developed suddenly in the 1890s, with Brisbane reaching a population of 120 000 by 1900. An engraved view of Queen Street, Brisbane in about 1886 shows broad, well-paved streets with stately buildings and a tram system (see Source 11.19). Perth was late in growing to a population of 60 000 by 1900.

Australia’s ports: hubs of the industrial world

Australia had important ports, such as Sydney, as early as the eighteenth century, but these grew as they became busy centres of trade for the industrial world. Australian wool was exported to meet the needs of the British textile industry. In return, British manufactured goods and luxuries were imported to meet the demands of the colonies. Within a few years during the Industrial Revolution, sailing ships also began to be replaced by modern steam-powered ships.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 11.8

- Determine why the discovery of gold in Australia caused a population boom.

- Explain how the Australian gold rush created an increased demand for new products.

- Look at the image of Brisbane depicted in Source 11.19. How does this view of an Australian city compare with images of English cities of the same time? Think about the relative width of the streets and compare the population levels.

Experiences of ordinary men, women and children

Life in England

For the millions of people who left their country villages to come to the city, the Industrial Revolution seemed to promise good work and a good wage. In many cases, these hopes were quickly dashed. For most, work in this new world meant very long hours in dangerous conditions for inadequate pay. For others, the new cities offered only unemployment and poverty.

The industrial city

The Industrial Revolution created large cities and towns, in which the living conditions for ordinary people were very poor. The need to accommodate all of the new workers in the factories forced the rapid construction of cheap housing, resulting in new suburbs of extremely poor quality. Government officials noticed these problems, and frequently sent observers to report on living conditions.

Factories

The new factories seemed enormous compared with the small workshops people were used to.

This was depicted in the paintings of Eyre Crowe, who went to Wigan to study the people who worked in them. His painting, The Dinner Hour, Wigan, accurately shows known buildings such as the Victoria Mills owned by the industrialist Thomas Taylor. Artists often sold their paintings to wealthy industrialists, who expected them to be accurate. If you look online for this painting you will see that the painting still has some limitations as a source for the historian. It only shows the factory girls resting, not working. They are taking a meal break, and seem happy and relaxed. They are well dressed – only one is barefoot – and clean and healthy. A policeman patrols the street behind them, suggesting that everything is in order.

The painter might have depicted a very different scene if he had gone inside the factory. In most factories, people worked long hours and received low pay. If the workers demanded better wages, the owners dismissed them and took on other desperately poor workers instead.

Moreover, the factory you see probably lacked safety equipment. The industrialists argued that safety equipment cost money but made no profits, so there was no point buying it. In the cotton mills, for example, young women like those in the painting worked for years in a factory where the air was full of fine cotton dust. When they breathed it in, it filled their lungs, causing lung disease and finally death. It was possible to buy large extractor fans to remove the cotton dust, but many industrialists argued that it was cheaper to hire new workers to replace those who died.

Child labour

One of the worst problems in the new factory was the use of child labour. By law, a child was not allowed to work until the age of six, but few factory owners obeyed this rule.

Once they were employed, children worked very long hours. Those who fell asleep were whipped by their employers to stay awake; some were so exhausted they fell forward into the working machinery and were killed. In some factories, children were employed to use their small hands to clean out the machines while they were still operating, and many were injured when their hands got caught in the moving parts.

Warning voices

Some of the strongest warning voices of the Industrial Revolution came from the industrialists themselves. Many were businessmen who believed that making profits was the only thing that mattered.

They thought social problems only occurred because working people were lazy or drunk.

Others saw the truth. The Industrial Revolution itself was creating bad working conditions, low pay, bad housing, poverty and unemployment.

Robert Owen was a rare industrialist who bravely stated that bad working conditions were the main cause of the dirt, violence and crime in the industrial cities. He suggested that if owners improved the conditions in the factories, workers would also improve their behaviour.

To prove his point, he built a mill at New Lanark, near Glasgow in Scotland. He paid for large windows to let in light and air, plus proper toilets, drainage and even baths. He cut down working hours. He made sure that workers had free time, and encouraged them to read or to exercise during that time. He refused to employ children under the age of 10. He hoped that industrialists would see his successful factory and copy his reforms. When that did not happen, he went straight to the English parliament and persuaded Sir Robert Peel, the then Prime Minister, to pass laws to improve conditions in factories.

He even showed working men how to form a trade union. He was so committed to reform that he spent his fortune on ideas to improve the lives of working people.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 11.9

- Assess why many industrialists during the Industrial Revolution avoided buying safety equipment.

- Determine the age at which children should be allowed to start work. Include your reasons in your answer.

- Imagine you are a child working in a coalmine during the Industrial Revolution. In a short paragraph, describe your day.

- Explain why Robert Owen’s reforms affected the output of his factories.

Conflict: ‘capital’ versus ‘labour’

Workers’ conditions during the Industrial Revolution were shaped by the desire of the owners of the new factories to make as much money as possible. Employing hundreds of workers, some owners thought that they needed to pay as little as possible in wages to their workers. The workersoften had to work long hours, in dangerous conditions, for a wage that was hardly enough to live on. Sometimes workers tried to go on strike, refusing to work until they were given better wages. The employers fought back by dismissals (getting rid of workers), lock-outs (shutting down their factories for a time) and importing labour (getting other workers from areas where there was unemployment). The workers fought back by forming trade unions, in which all members of a trade promised to strike together and support each other. By the 1840s, thinkers like Karl Marx were saying that there was a sort of war between the ‘capitalists’ who owned the factories and the ‘labour’ who worked for them.

For all working families, life was a struggle and could be ruined by just one event such as the death of the male wage-earner. A fatal accident in a mine or a textile mill could leave a woman and her child without enough money to pay the rent or to buy food. In these situations, families were often evicted from their homes, and left to descend into a life of poverty.

The Poor Law of 1834

The group called ‘the poor’ was made up of the destitute – or those who could not work because they were elderly, sick or injured – and the unemployed, meaning those who were able to work but could not find a job. Until 1834, there was some support available for both types of poor.

In 1834, a new Poor Law stated that only the ‘sick poor’ – old people, orphans and the seriously ill – should be given money. The ‘able-bodied poor’ – healthy unemployed workers – should be forced to search for work. The problem was that this assumed that people were unemployed because they did not want to work. It ignored the fact that all economies have an amount of unemployment. The able-bodied poor were forced to live in workhouses, and received only the bare minimum of food.

Poor Law Commissions controlled the workhouses across the country. These commissions instructed that the workhouses must be less attractive than living in poverty and be made more like prisons. People were humiliated, given harsh discipline and were badly fed. The aim was to make life so miserable that the poor would learn their lesson and go and find work. Many preferred to starve in a cottage than to go to the workhouses, seeing it as a fate worse than death.

These ideas cut the cost of poor relief, but at the price of human misery and suffering.

Life in Australia

The Industrial Revolution transformed the world of work for many Australians. The textile and clothing trades, for example, quickly became large industries. By the 1870s, there were several large textile mills in New South Wales and three in Victoria. As in Britain, the growth of these industries in Australia caught the attention of artists, who made images of the great new workplaces and their machines. The engraving reproduced in Source 11.22 depicts the large workshop, its many machines (all driven by the new power of steam) and the top-hatted owner visiting to talk to the foreman.

This picture gives us little information about the lives of the human beings who worked here. These women worked long hours for a small wage. At the Victorian Woollen and Cloth Manufactory in Geelong, for example, all worked a 60-hour week; men were paid a low wage of 35 shillings per week, but women received only 10 shillings. The mill illegally employed children who had run away from school, paying boys 7 shillings and girls 4 shillings a week. Poor families could not resist signing all their members up for work, but their children received no education, and were committed to factory work forever.

In these conditions, a worker’s health was seriously affected. A little girl was brought to me three days ago by her mother, a little worn-out looking thing. She had been in the factory twelve months … already, and she is only thirteen now. She is like a little old woman, pale and shrivelled, and suffers from palpitations of the heart.

Source 11.21 A doctor reporting on the state of health of a child patient