11.1 Causes of the Industrial Revolution: society and innovation

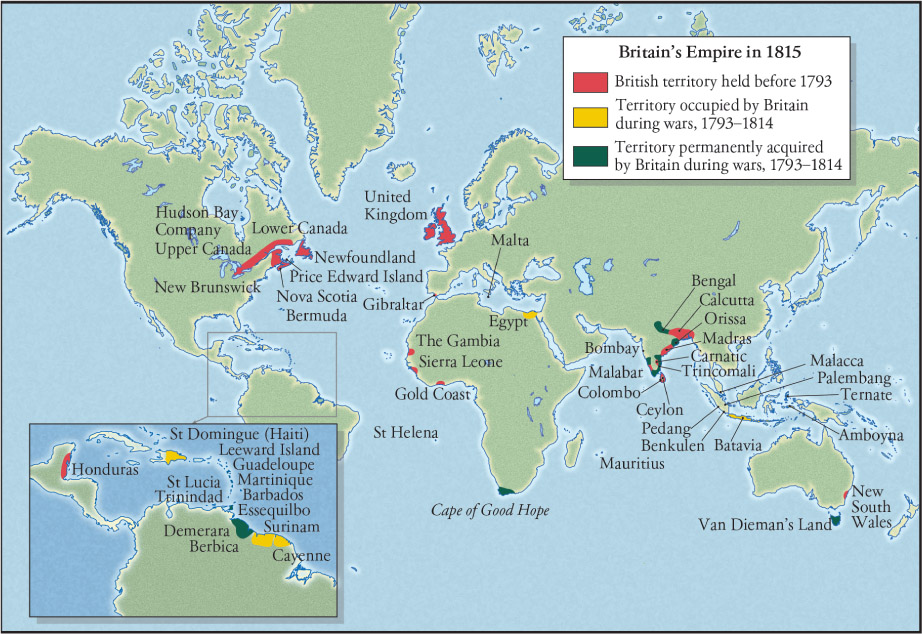

The British Empire

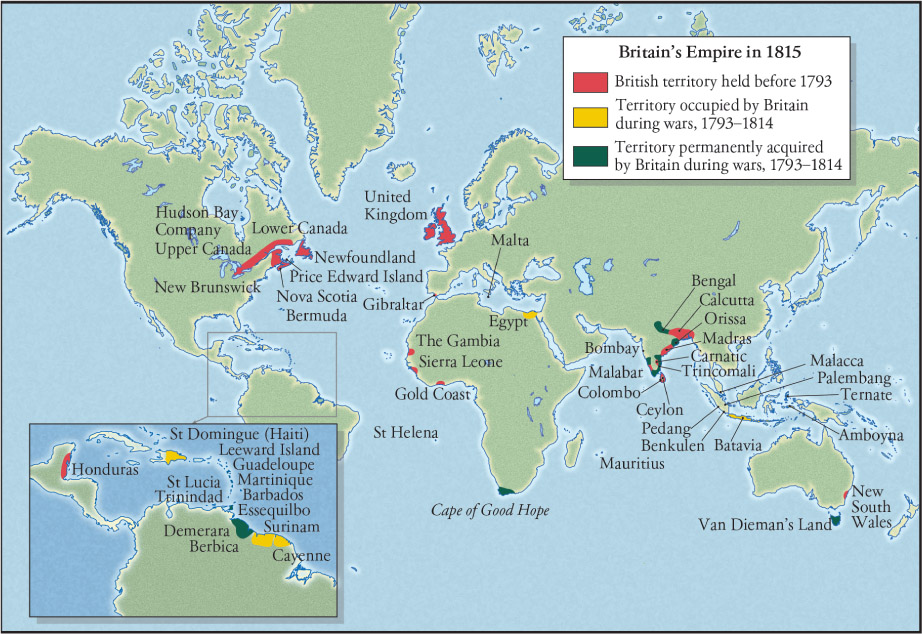

Perhaps the central reason for Britain’s rapid economic growth at the time of the Industrial Revolution was the success of its overseas colonies. The British were experts in developing a colonial system. Using their powerful navy and their merchant ships, they created colonies in countries like America, India, Jamaica and Australia, often displacing and subjugating the native populations.

Britain drew massive resources from its empire.

By the year 1800 this empire was enormous, and Britain could obtain goods such as sugar from Jamaica, and wheat and wool from Australia.

Through the exploitation of slaves and native workers, the British could produce these items very cheaply and sell them for vast profits in Europe.

British merchants also made a great deal of money by the slave trade, which involved buying slaves in Africa and selling them to the tobacco plantations in the American colonies. This soon developed into a three-way shipping route, because the ships then sailed back carrying American tobacco and cotton that could be sold at good prices in Europe.

All of the wealth generated by the British colonies meant that there was plenty of money available for investment. As settlers in places such as Australia made money in industries such as wool, they tended to invest their new wealth in British industries. This in turn allowed British industrialists to borrow money to buy new machines and to expand their factories.

These colonies also provided new markets for British manufactured goods. In Australia, people bought machinery, furniture and clothing from ‘the home country’. In some cases, people were even forced by law to buy British goods, even though they could make such goods themselves.

For example, the people of India were already able to spin cotton themselves on small looms, but British laws prevented them from doing so.

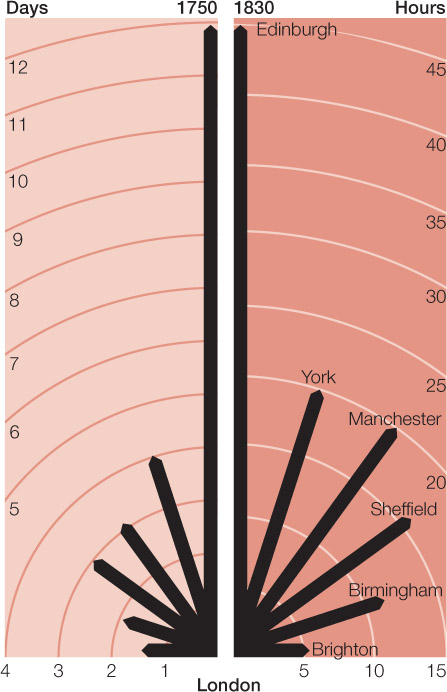

As a result, millions of Indians had to buy British cotton. This quickly had an effect. Between 1750 and 1770, the amount of goods produced to be sold within Britain increased by only 7%; at the same time, the amount of goods produced to be sold to the colonies increased by 80%.

‘Explosion of invention’

The wealth generated by the empire fuelled innovation and invention, the drivers of the Industrial Revolution. Between about 1750 and 1800, many important inventions transformed industrial production, especially in metal and textiles.

The first great change was to energy: human labour and animal labour were replaced by steam, then gas and electricity, giving people power such as they had never had before.

The second great change was to machinery: there was an unstoppable flow of new inventions and new techniques that transformed the way important things such as coal and steel were made.

The third great change was to the scale, or size, of production. There had been a few large factories before 1750: as early as the 1600s, Ambrose Crowley was running a large iron-making factory at Winlaton. In the 1700s, however, many more industries – but not all – changed from many small workshops to large factories employing hundreds of people.

The fourth great change was to transport: the creation of a railway system and a canal system allowed the rapid movement of resources into industrial areas, and the efficient movement of their products to markets.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 11.1

Technology of movement

Assisting the worldwide movement of goods, money and technological development was a revolution in transport infrastructure and technology. Britain is criss-crossed by rivers, which were extended in this period by a network of canals.

New forms of transport – railways and canals – were particularly good for moving heavy goods over long distances.

As an island nation, Britain possessed a powerful navy and a large merchant fleet. It also had a long coastline, with many ports. It was also strategically located: its ships could reach Europe to the east and America to the west. These geographical advantages meant that Britain was in a good position to conduct trade with its colonies and other nations.

By the year 1850, Britain was one of the most important industrial economies of the world. For example, it made some 90% of the steam engines produced in Europe.

Population growth

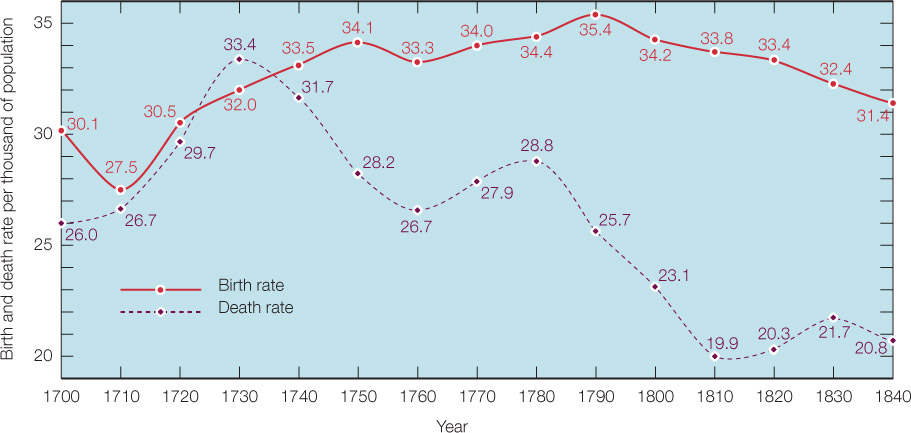

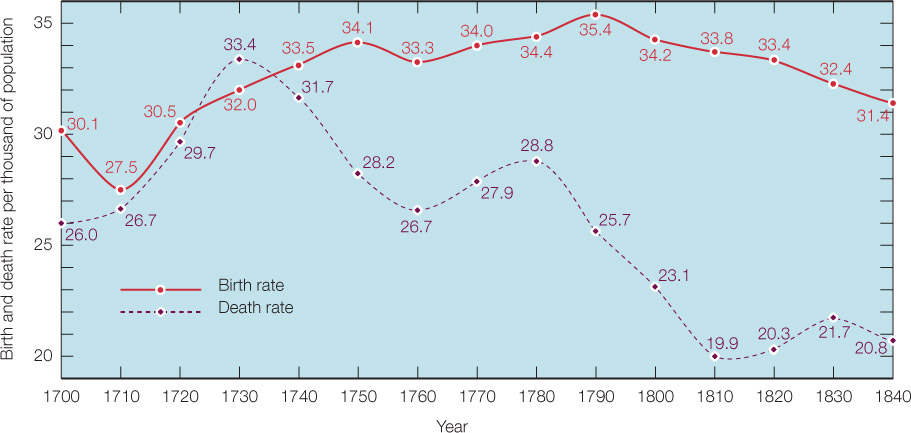

From about 1800 onwards, Britain enjoyed an increasing population. In 1770, the population was 7.4 million; by 1840 it had doubled to 15.9 million. This happened quite simply because people were generally healthier than previous generations; with higher wages and better food, the birth rate increased and the death rate steadily decreased.

This led in turn to some increase in the standard of living. This further increased the demand for goods and services, thus speeding up economic growth. However, this increase in the standard of living was unevenly shared, with some areas (such as the industrial Midlands) remaining poor.

The agricultural revolution

Over the course of the eighteenth, nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, millions of British workers moved from the country to the cities.

This population shift meant that the factories of the Industrial Revolution had the workers they required. One of the central causes of this shift was a revolution in agriculture.

New machines

Jethro Tull invented the seed-drilling machine in about 1701, which scattered seed into the soil.

Before long, inventors designed mechanical ploughs, reaping machines and threshing machines. The Rotherhan triangular plough (1730), for example, turned over the soil more effectively before planting a crop. Andrew Meikle invented a threshing machine in 1786. The only task that people could not do by machine was hay making, which was done by hand. As the new machines became available, many farm workers became unemployed. Some went to the industrial cities to get jobs in the new factories. Some formed bands under a leader they called Captain Swing, which broke up the new machines and attacked farmers who used them.

Changes in the use of the land

People also realised that they would need to make more efficient use of the land. This led to a new system that helped rich landowners but harmed poor farmers and people without land. This was known as the ‘Inclosure’ Movement (now spelt ‘enclosure’), which started with an early Act of Parliament in 1773, and was completed by fifteen more Acts between 1845 and 1882.

For centuries, most parts of central England had common lands that could be used by all members of each village. In addition, the landowners did not fence off their fields, and there was a traditional, unwritten agreement that villagers could make some use of their land. For example, a poor villager could let their cattle feed on the land at times when there was not a crop growing there.

There were other understood ‘rights’: a poor farmer could let geese feed on the land and could let pigs search for food. People could pick wild berries, chop wood for the fire and ‘glean’, which meant picking up pieces of wheat left over after the harvest had been finished. These might sound unimportant, but they actually meant a lot to poor farmers who struggled to make a living.

From 1773, people could ask parliament’s permission to ‘enclose’ land. Enclosure meant putting a fence around an area of land. It was then ‘deeded’ (legally given) to one or more people. It became completely private property, and nobody else could use it. Those who had lost the use of the common land were given some strips of land as a replacement, but it was often of poor quality. By the end of the nineteenth century, 28 000 square kilometres of land – about 21% of the land in England – had been locked up in private ownership. Many poor farmers and people without land could no longer make a living, and left the countryside to work in the factories of the industrial cities. There was no doubting the effect on the population: as early as 1770 the writer Oliver Goldsmith had written a book called The Deserted Village, warning that the English countryside was being emptied of people.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 11.2

- Analyse the advantages that the locations of Britain’s ports gave it when conducting trade.

- Describe why the increase in the standard of living during the first half of the nineteenth century was unevenly shared among the population.

- Discuss why Captain Swing’s bands tried to break up the new farming equipment.

- Think about what your life would be like without quick and reliable transport – without cars, trains or buses. Write a short paragraph that describes what your day would be like without these technologies.

Limitations of cottage production

The Industrial Revolution did not create Britain’s industries – they already existed – but it completely changed the way they worked. By the eighteenth century, Britain was already a leading industrial nation. It sold large amounts of iron, coal, wool, copper and tin to other countries. Several cities already had important industries: Birmingham, for example, specialised in producing goods made of iron or brass, such as nails and kitchen utensils. The city of Stourbridge specialised in glass making.

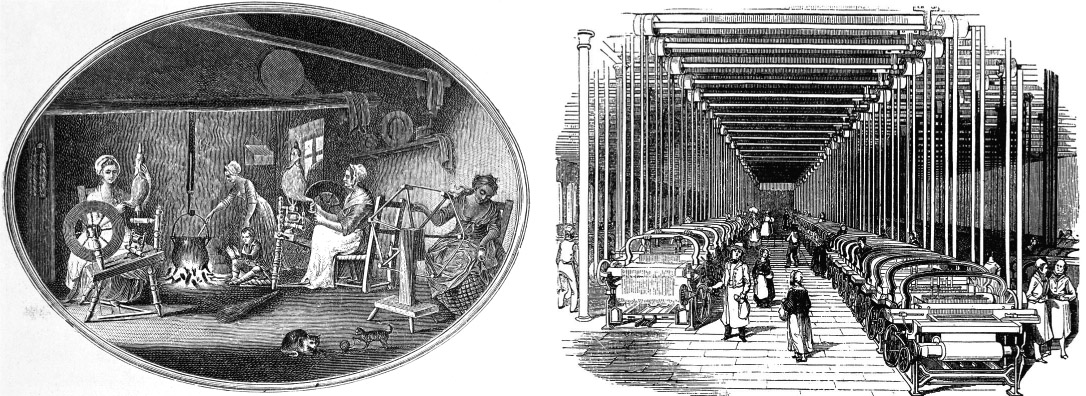

In some industries, however, production was limited by the simple techniques being used. One of the most valuable industries was textiles, which includes the weaving of cotton cloth and the making of items such as stockings. The domestic system meant that a family in a country village might have a loom or a stocking knitting frame in their own cottage. Often the woman of the family spun the wool or cotton and wove the cloth.

Her husband then took the fabric to the nearest town to sell at market. In some places, such as Lancashire, households were more organised, with clothiers providing the raw material to a number of households, paying them for the fabric they made.

In English cities, production took place in a small workshop run by a master. He, too, was supplied raw materials – wool from a clothier or iron from an ironmaster – and made an agreed number of items at a set price.

Conditions were poor in both the cottage industries and city workshops. Businessmen kept wages low by encouraging young men and women to come to the city, creating crowds of workers desperate to be employed at any price. Many had to work 14 hours a day. The businessmen refused to buy basic equipment such as chairs: often tailors had to sit cross-legged on the floor.

They did their fine work by candlelight, and many finally went blind.

Revolution in energy: new forms of power

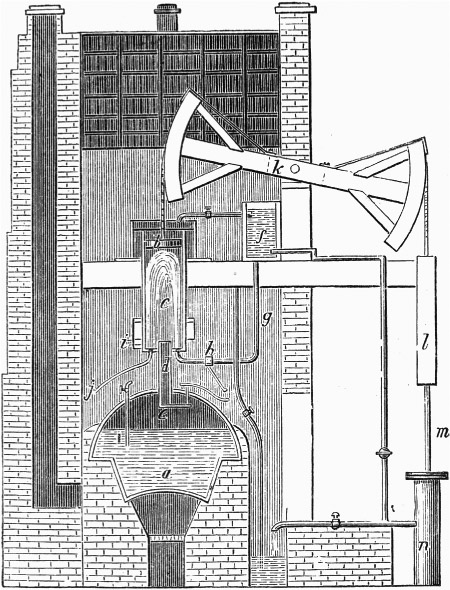

Until the eighteenth century, the power needed to do work came from humans, from animals such as horses or from natural forces like wind and water. To complete more work, people needed a new and more powerful form of energy. They found it in the power of steam.

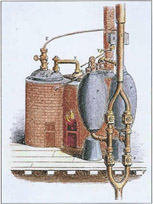

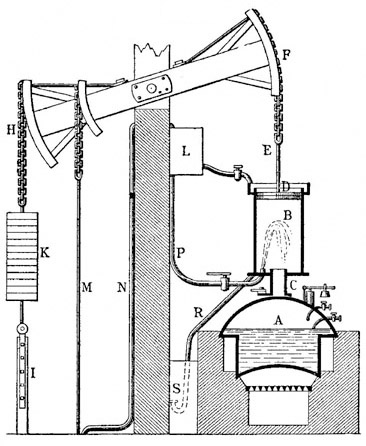

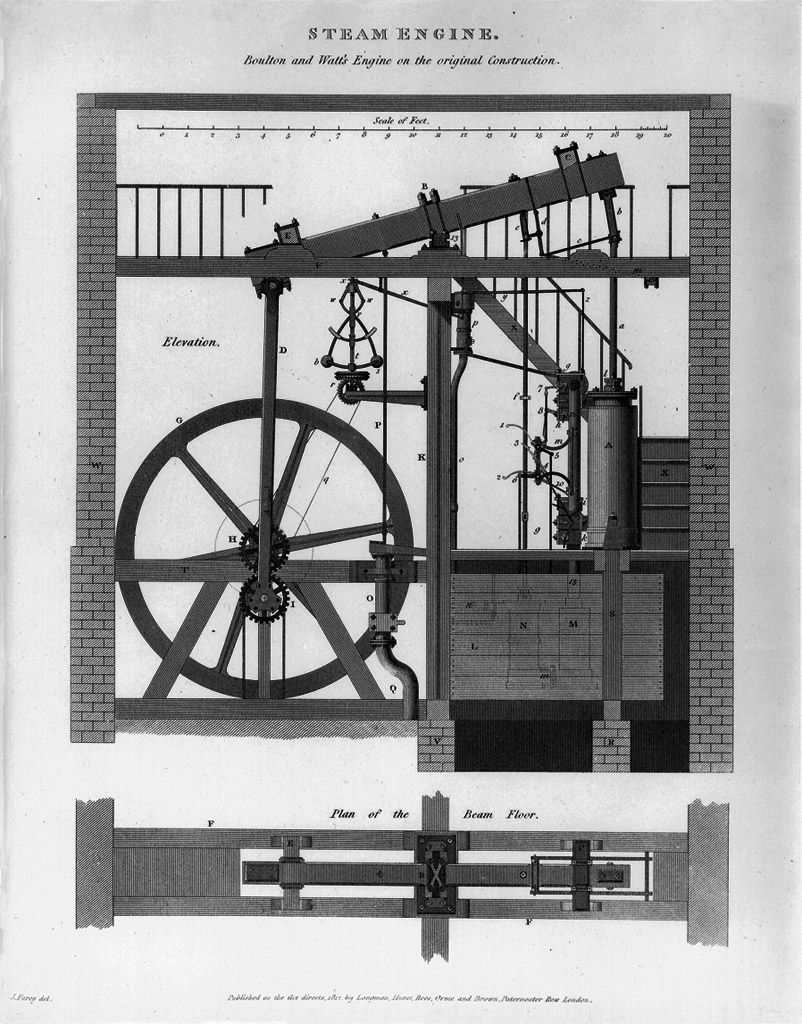

The discovery of the power of steam goes back to the ancient Greeks, who understood that when water is turned into vapour by heat it expands 1800 times, releasing an energy that can be captured and used. Thomas Savery designed an industrial steam engine as early as 1698, which Thomas Newcomen improved upon with a more powerful steam pump in 1710–12. James Watt invented and developed the modern condensing steam engine between 1763 and 1775 by improving the existing Newcomen steam engine. It was so powerful that it could haul coal up mineshafts and drive the heavy machines in cotton mills, breweries, paper mills and other factories. Once it was harnessed to locomotives, it had the power to haul heavy loads such as iron over long distances. Later, it would be harnessed to shipping, creating the modern ‘steam ship’.

In this ABC video, Kevin Dale of the Pichi Richi Railway Preservation Society explains how a steam locomotive works: https://www.cambridge.edu.au/redirect/?id=209

Australian cities were greatly improved by the introduction of city lighting, first by gas and then by electricity. The cities seemed transformed: the weak and flickering gas light was replaced by the strong, steady blaze of electric light. The first electicity company was the Australian Electric Light Company in Melbourne in 1879; by 1886 an enormous generator had been built under the General Post Office and was capable of lighting two thousand bulbs in the building. In Sydney, Brisbane and Hobart, the introduction of electric lighting was delayed by the resistance of the gas companies, but electricity was increasingly used to power factories. By the 1890s, the first electric cables were raised in the streets of Perth.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 11.3

- Discuss how businessmen were able to convince so many people to move to the city during the Industrial Revolution.

- Describe a common feature of the industries that were strong in Britain at the beginning of the eighteenth century.

- Explain why it was the husband, not the wife, who usually sold the finished cloth at the market.

Transformation of the coal industry

After the introduction of the steam engine, the demand for coal increased rapidly. Britain had many coalfields, ranging from Northumberland and the Scottish Lowlands to Yorkshire, Nottinghamshire and the Midlands, along with large deposits in Wales (see Source 11.6). These coalfields were already being used to provide fuel for heating in large cities and to power existing industries.

After 1750, coal was needed mainly for the manufacture of iron. Iron was needed for the making of bridges, railways, locomotives and weapons. Coal was also used for baking bricks, making pottery, tiles and glass, and for the brewing of beer.

Dangers of deep coalmining

A persistent problem with coalmining was that existing techniques were limited by the dangers of digging shafts. These shafts could collapse or fill up with water or explosive gases. As late as 1760, most mines could not go deeper than 200 feet. Another problem was that the work down in the mines was done by human labour. Men crawled along the shafts to the coalface and dug the coal with pickaxes and crowbars. They threw the coal into baskets, which were put on wooden sleds or trolleys and dragged back to the surface by women or children. Accidents were common, and when a shaft collapsed many people could be trapped underground, with little chance of being rescued. The tragedy of these deaths captured the imagination of artists such as John Longstaff, who showed their effects on the families of the dead miners (see Source 11.7).

The coalmines employed many women and children for the heavy task of carrying the coal up to the surface. Children had to crawl on hands and knees, pulling a small trolley that was harnessed to their backs. Women had to do the heavy task of carrying baskets of coal up ladders to the surface high above. In 1842, a Parliamentary Commission into the issue published its shocking findings, accompanied with pictures, resulting immediately in a new law forbidding the use of children under 10 years of age in coalmines.

New technologies and the growth of coalmining

The Industrial Revolution provided solutions to some of these dangers. In 1800, the Newcomen steam pump was modified to draw water out of the mines. In 1807, engineers designed an air pump to push fresh air into the shafts. By 1842, there were strong wire cables available, which allowed lifts to bring both coal and miners up out of the deep shafts. Production began to increase to meet the steady demand: in 1700, British mines produced only 2.5 million tonnes of coal. By 1760, this had doubled to 5 million, and by 1800 it had doubled again to 10 million tonnes. Coal became the lifeblood of the Industrial Revolution, and for the first time supply met the demands of hundreds of new factories.

Transformation of the textile industry

Of all Britain’s industries, the cloth industry was most transformed by the new machines of the Industrial Revolution. Britain already produced large amounts of wool, but the new technology now allowed it to produce cotton. By 1823, Britain exported more cotton than wool. This industry was located in areas such as Lancashire and Derbyshire, where the damp atmosphere helped spinning. There was also plenty of clean water for cleaning the cotton.

The slave trade also had a great impact on the cotton industry. Traders bought slaves in West Africa and sold them in America, where they worked on cotton plantations. The extremely cheap slave labour put vast profits in the hands of cotton merchants and the owners of cotton plantations and factories.

When machines became available, cotton traders gradually moved away from the old domestic system towards the factory system, in which they built the factory, bought the cotton, and brought the workers to one central place. It was not an immediate change: there were many more cotton-spinning mills after 1780, but they did not take over completely until 1850.

New machines, new solutions

Once the factory system was set up, the new machines quickly solved the central problem of cotton manufacture: that the spinners who made the thread could not work quickly enough to supply the weavers who wove it into cloth. The first improvement was made by John Kay, who invented the flying shuttle in 1733. He intended to use it to weave wool, but it was quickly applied to cotton. In 1748, Lewis Paul invented a machine for carding, the process of combing the raw cotton to remove tangles and to make it smooth. Next, James Hargreaves invented the spinning jenny in 1764. He found the idea simply by watching his wife using a traditional spinning wheel, which could only produce one thread at a time. He created a new wheel that could operate eight spindles at once.

He then used this to create a spinning factory in Nottingham. He in turn was soon outstripped by Richard Arkwright, who invented a thread-drawing frame powered by water, called a water frame.

These two machines then inspired Samuel Crompton to invent the spinning mule in 1775.

It used features of both the previous machines and was able to spin very long and fine thread, making it possible to weave fine muslin fabrics.

By now, the problem had been reversed: yarn could be spun more quickly than the weavers could turn it into cloth. In 1785, Edmund Cartwright invented a power loom for weaving, although this invention took longer to perfect.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 11.4

- Discuss the advantages of the factory system compared with the domestic system.

- Research the spinning jenny on the internet or in the library. Draw a diagram of it, including its eight spindles.

- Explain why the production of cotton in Britain outgrew the production of wool. Think about where each of these products came from.

New forms of power

As well as inventing new machines, new types of energy were used to power them. At first, the powerful rivers of the area drove the machines.

Later, steam power was used. James Watt’s steam engine was introduced into the cotton factories in 1789; by 1815 power looms were widely in use. The use of steam-powered machinery was concentrated in areas close to the coalmines of Yorkshire.

Success of the cotton industry

These changes meant that the cotton industry grew remarkably rapidly. In 1700, Britain only imported one million pounds weight of cotton; by 1789 the figure was 5 million pounds, and by 1795 it was 11.5 million pounds. By 1815, the cotton industry employed 100 000 workers in factories, backed by another 250 000 weavers working outside the factory system.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 11.5

- Explain why steam-powered machinery was concentrated in areas close to Yorkshire’s coalmines. Think about the transportation available in Britain at the time.

- Determine why slave numbers increased after the invention of the labour-saving cotton gin.

- Describe what English consumers of cotton might have thought about slavery.

- Imagine you are an English worker, and have just been informed about the use of slaves on United States cotton plantations. Write a paragraph describing your thoughts.

Effects on the southern states of the United States

The explosion of cotton production in Britain affected other countries. Britain now needed massive amounts of raw cotton, which was first imported from the West Indies and then from America. Plantation owners in the southern states of the United States were keen to supply it. The only problem holding back production was the process of cleaning cotton: slaves had to pick the seeds out of the cotton by hand.

In 1793, Eli Whitney, a schoolteacher, invented his cotton gin. This machine had rollers fitted with metal spikes and brushes that lifted the seeds out much more quickly than humans could. The first machine was turned by hand, and allowed the worker to clean 50 times as much cotton as before.

Source 11.10a Cotton gin (00:35)

Later, the machine was powered by water, and allowed a thousand times more cotton to be produced in a day. Even later, the Americans found that they could also use the seeds to make cottonseed oil for lamps and feed for cattle.

By about 1800, the cotton industry had replaced the tobacco industry as America’s main export. The states of Georgia, North and South Carolina, Virginia, Tennessee and Alabama were heavily involved in cotton plantations. The owners referred to their crop as ‘King Cotton’. However, because of this growth Americans now used even more slaves than ever to work their plantations. In 1790, there were 700 000 slaves in these southern states; by 1860, there were 4 000 000 – a human tragedy on an enormous scale.

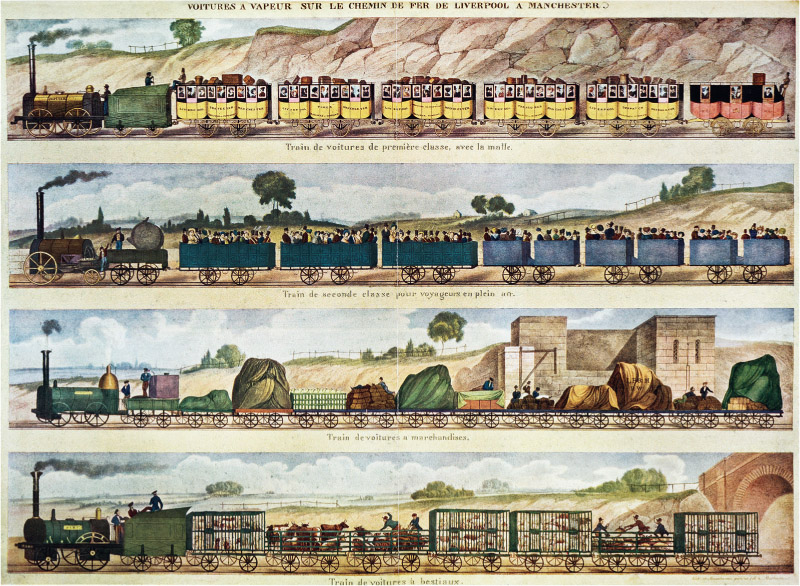

Transport revolution: railways and canals

Roads of steel: the railway network

The idea of the railway already existed in a simple form before the Industrial Revolution.

Rails were used to move carts of coal from mines, but the rails were made of wood and the carts were pulled by animals. It took the inventor Richard Trevithick to realise that the new steam engine could be placed on a vehicle and made to turn wheels. By 1801, he had designed a simple vehicle called ‘the puffer’ to run on roads. Then, in 1804, an owner of an ironworks made a bet that it was possible to design a vehicle that could run on tracks, pull carts containing 10 tonnes of iron and run for about 15 kilometres. Trevithick designed the first locomotive, and proved that a steam engine could pull carts.

Others took up his invention. William Hedley built a train called Puffing Billy in 1814 at Wylam, Northumberland. George Stephenson built another train, the Blucher, to pull coal wagons at the Killingworth coalmine.

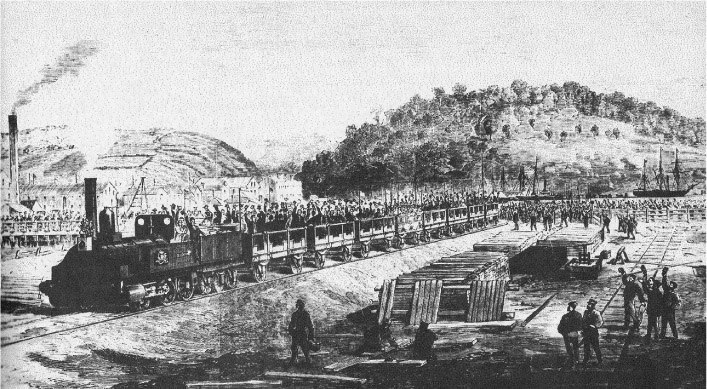

Stephenson first became famous for building a railway from the coastal port of Stockton to the coal town of Darlington. In 1825, some 40 000 people saw the grand opening of the railway. They were amazed to see an engine, the Locomotion, pulling six cars of coal, a carriage for the railway’s committee and 20 more carriages for the people who had invested their money to support the project. Because of fears for safety, the train travelled slowly behind a man carrying a red flag!

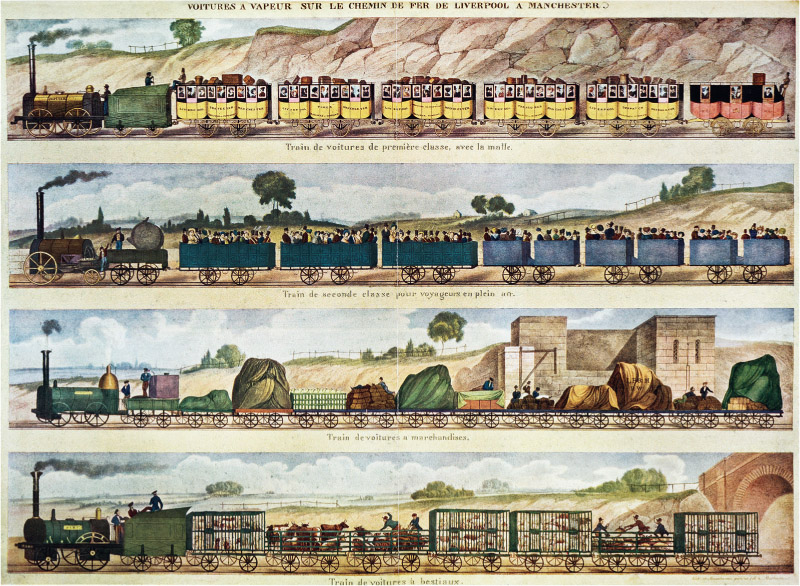

The great age of the railway really began in 1826, when the British parliament gave permission for the building of a railway line from the industrial port of Liverpool to the manufacturing town of Manchester. By 1829, the line was completed. It was time to test whether a locomotive could travel efficiently over such a long distance. Stephenson used his Rocket and covered the 30 miles at a speed of 14 miles per hour. The line opened in 1830.

This provided the basic idea for the steam train. In this video from the Newton Channel, John Liffen of the UK Science Museum explains why Stephenson’s Rocket was so significant: https://www.cambridge.edu.au/redirect/?id=210

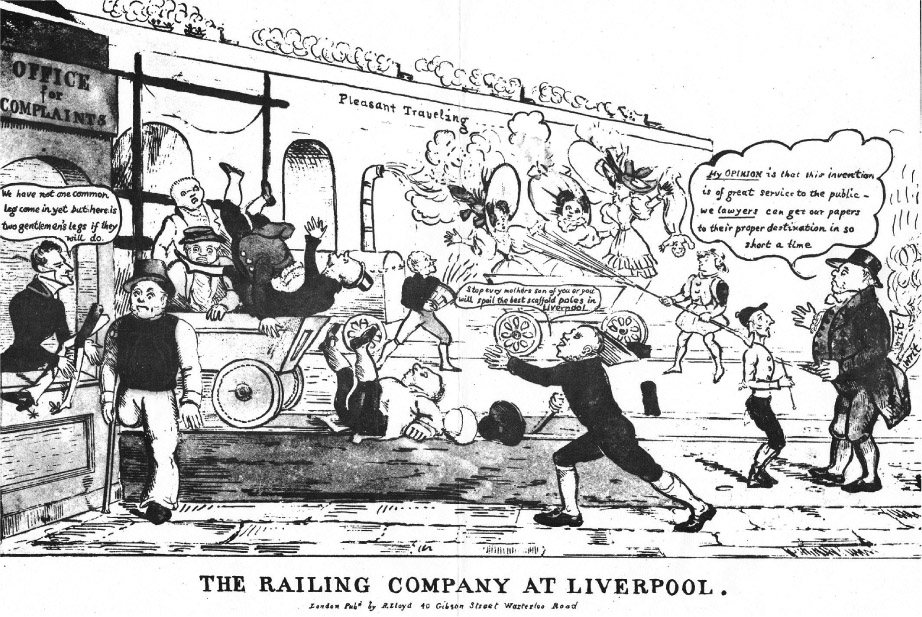

The arrival of the first trains caused a scare campaign, with claims that the high speed of the train would cause the two sides of the human brain to fall apart. This was of course rapidly disproved!

Fear of new technology

The pace of social change caused many to become frightened and upset. The public reaction to the emergence of the steam train is a good example of the fear that new technology caused. Farmers argued that their cows would be frightened and not give milk, and that their horses might run in terror. Others hated the way the railway lines cut across the countryside, and said that the smoke would kill birds.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 11.6

Examine Source 11.12 and then complete the following tasks:

- Articulate whether you feel that cartoons published in newspapers at the time are a good way of understanding how people felt about a particular issue. Explain the reasons for your answer.

- Explain what the cartoonist meant by drawing four trains end-to-end up on the bridge.

Another cause of criticism was financial.

Businessmen who owned canals, roads and coaches all charged high fees for transport.

They saw that if the railways succeeded, their own businesses would make less money. Not surprisingly, they contributed to the scare campaigns against railways.

People often express their feelings and their fears through cartoons. This is a two-way process.

Cartoonists often highlight events of the day, summing up what people are thinking and saying; that is, successful cartoons recognise the way many people feel about a particular subject.

At the same time, cartoons might strengthen the feeling of fear by confirming it. Source 11.12 is a good example of this.

Triumph of the railways

The scare campaign did not stop the railways.

First, businessmen realised that there was a fortune to be made in transport. In 1838, a group of businessmen opened a new line from London to the northern city of Birmingham. By 1840, dozens of companies, financed by thousands of investors, had built lines between London, Brighton, Exeter, Leeds and Manchester. By the 1860s, new lines had reached out to the farthest parts of Britain, including Cornwall in the south, Wales in the west and Scotland to the north.

Canal network

The businessmen of the Industrial Revolution realised that they could not increase their production and sales without a better transport network across England. The existing roads could not carry heavy traffic efficiently. Roads were supplemented by small ships carrying coal and other cargo along the coastline. The businessmen needed more: they needed to carry heavy loads to inland factories. They found that the rivers – the Thames, for example – could be made suitable for cargo boats. They arranged for the riverbanks to be widened, and the channels deepened. However, this did not help factories that weren’t close to a river. In 1753, a group of businessmen in Liverpool made an important discovery: if there wasn’t a river where you needed it, you could create one. They paid the engineer Henry Berry to create a canal from the coalmines at St Helens to the town of Warrington. This first canal was called the Sankey Brook Navigation, and was open for business by 1757.

The idea caught on. The Duke of Bridgewater, who owned a coalmine at Worsley, also wanted to avoid moving his coal by road, due to the high costs. He asked parliament permission to build a canal from Worsley 15 kilometres overland to join a river near the industrial town of Manchester.

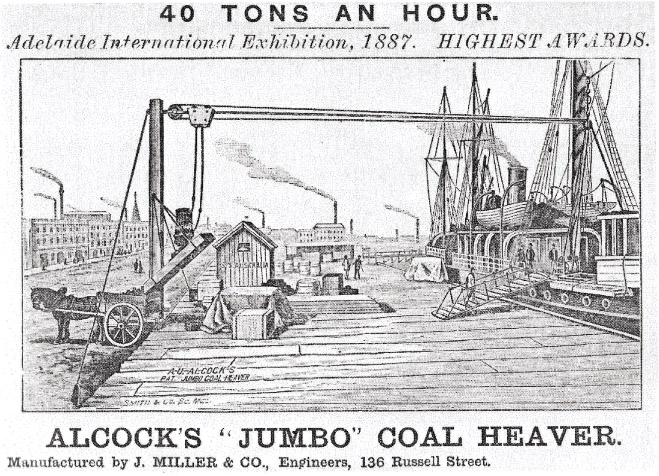

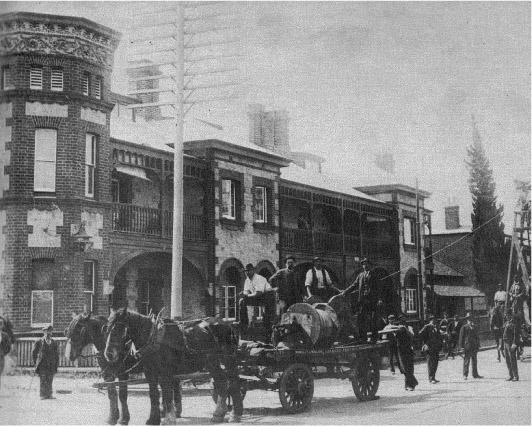

Australians did not merely copy English technologies: they proved to be excellent inventors themselves. In Adelaide, for example, people marvelled at the cleverness of the inventor Alfred Upton(AU) Alcock, who demonstrated how to use a steam engine to quickly unload coal from a ship, moving 40 tonnes in just 1 hour.

Railways in Australia

The Industrial Revolution made an important difference in a vast continent such as Australia because it helped to shrink space and distance.

In every colony, the city was linked to its suburbs and to the countryside. Australians started work early on the railways, and they developed quickly. In New South Wales, England’s railway boom in the 1840s almost immediately inspired Australians to build a network. As early as 1846, businessmen formed the Sydney Tramroad and Railway Company to build a line from Sydney to Goulburn. The line was begun in 1850 and finished in 1855, with the help of 500 rail workers imported from England. In Victoria, the Melbourne and Hobson’s Bay Railway Company was opened in 1854, becoming the first steam train service to operate in Australia. In South Australia, a line from Goolwa to Port Elliott was opened in 1854. In Queensland, a line from Brisbane to Toowoomba was opened in 1864. In Western Australia, a railway from Northampton to Geraldton was opened in 1879. During the rest of the nineteenth century, the large network of tracks was extended, especially when colonial governments took over from private companies the expensive business of building railways.

The steam engine also transformed life within Australian cities. The existing horse-drawn trams were replaced by steam-driven machines, which provided faster travel around the town and out to the expanding suburbs.