10.5 Economic, social and political ideas

Revolutions, independence and equality

In Europe in the seventeenth century, a period of religious warfare was followed by an era of absolute monarchy, with an ideology of the divine rights of kings and queens, and expanded control by the monarch’s central government.

Absolute monarchy was linked to strong royal armies. Monarchs sought to expand their territories, while emerging nation-states were represented by their king or queen. In England, after a bloody civil war in the 1640s, a bloodless revolution in the 1680s produced a new constitutional agreement between king and parliament. During this ‘Glorious Revolution’, the political philosopher John Locke developed his theory of liberalism. Locke suggested that power emanated from the people, not from a monarch’s supposedly divine right to rule, and that there were basic rights to freedom of person and property.

Locke’s political liberalism spread through the Enlightenment of the eighteenth century, and was dramatically enshrined by the American Revolution of the 1770s and the French Revolution of 1789–92. The American Revolution began with the American War of Independence against Britain.

Britain’s American colonies rebelled against British control, particularly in the form of duties and taxes. Tensions escalated into war in 1775. The American colonies established their own Continental Congress, which approved the Declaration of Independence on 4 July 1776.

The American colonies finally won independence from Britain in 1783, and their principles of political liberty gained global influence.

We hold these truths to be self-evident: That all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness; that, to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.

Source 10.11 A section of the American Declaration of Independence, drafted by the future president Thomas Jefferson

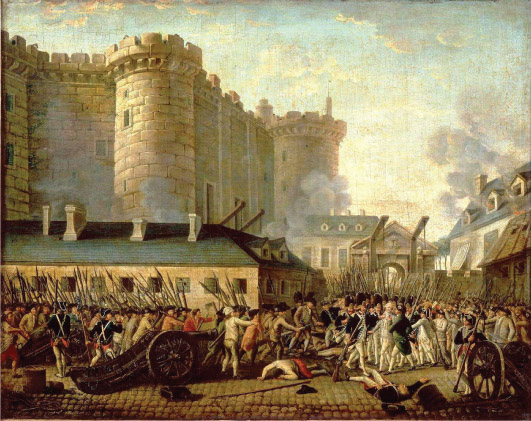

The French Revolution, which erupted in 1789, gained attention worldwide and has reverberated across the centuries since. The cry of ‘liberty, equality and fraternity’ that was the catchphrase of the French Revolution echoed around the globe, not least in France’s own colony of Saint Domingue (Haiti), which rebelled against French control and rang a death knell for the system of slavery there. The French Revolution asserted the political power of the masses, and the political ascendancy of the middle class, in a direct challenge to the feudally derived power of the monarch and the aristocracy. In 1789, the self-proclaimed National Assembly stood up to King Louis XVI, while crowds took direct action such as storming the Bastille prison and burning tax offices. Then there were widespread revolts by the peasants in the countryside. On 27 August 1789, the Assembly passed the ‘Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen’, a manifesto of political liberalism that began: ‘Men are born, and remain, free and equal in rights.’ In 1792, the French Revolution entered a new and bloody stage, in which the ideals of liberalism became overshadowed.

The French Revolution set the agenda for the nineteenth century in Europe, and had ramifications for the rest of the world. The power of the monarch and the aristocracy was curtailed, but in the decades that followed the differences in the demands of the middle class and the working class became increasingly apparent. In the nineteenth century, conservatives (supporters of the old order) struggled against liberalism (represented by the first stage of the French Revolution) and socialism, which was spawned following the French Revolution. These political struggles would be waged around the globe in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, as liberalism gained power and was contested by socialism and communism (from the 1840s). In the twentieth century, communist regimes would become locked in global ideological struggle with capitalist democratic powers led by the United States and Britain. The struggle between capitalism and communism also would become important for anti-colonial movements in various parts of the world.

Democratic values

Liberalism and political philosophies based on the rights of the individual spread globally from the eighteenth century. To some extent these ideas drew on ideals of democracy from ancient Greece and Rome, particularly those that originated in the Greek city-states from the eighth to the fourth centuries BCE. Because of the revolutions of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, ideas of constitutional democracy spread through the Western world. They included the consent of the people to be governed; the contract between the government and those governed; the balance of powers between legislative, executive and judicial arms of government; and basic civil rights.

Differences emerged between, for example, Britain’s Westminster system and its unwritten conventions, and the American system of a republic with a president (instead of a monarch) and a bill of rights.

Capitalism as an economic philosophy gained popularity in the mercantile world of the eighteenth century and later. In 1776, Scottish philosopher Adam Smith outlined his ideas on capitalism in his book The Wealth of Nations, emphasising individual choice, private enterprise and the operation of markets as opposed to state control of the economy. In the early nineteenth century, the opposing theory of socialism gained followers, with its principles of the ownership of land, capital and means of production being vested in the community or the state. French philosopher Charles Fourier and British industrialist Robert Owen put forward their theories of communal cooperation. Socialist movements and parties grew in the late nineteenth century based on concern for working people.

The creation of nation-states from former regions, empires and colonies has been a central development of the modern world. Many countries have struggled to achieve nationhood and sovereignty. Our concept of the nation dates from the eighteenth century, when it came to refer to a state in which citizens claimed collective sovereignty and a shared political identity. The idea of the nation emerged along with political rights and constitutions, instead of loyalty to monarch or church. Nationalism fuelled anti-colonial movements for independence from imperial powers, but it has also been linked to racism and hostility to foreigners. The roles and rights of nations have changed that Australians, for example, started to be issued their over time, as has national belonging. It was only in 1948 own passports separate from British ones.

Egalitarianism: social and political equality

In the nineteenth century, Australia became one of the world’s social laboratories, with various early steps in political progressivism. Following Canada’s lead, in the 1840s and 1850s the Australian colonies fought for self-government in evolving stages. Most Australian colonies received Responsible Government (constitutional self-government with bicameral legislatures) between 1855 and 1859. At the same time, well ahead of Britain and other countries, the Australian colonies introduced manhood suffrage; that is, the right to vote for adult, white men. In 1858, the secret ballot was first introduced – a progressive reform that meant voters would not be intimidated by having to vote publicly. In the 1890s, members of parliament were first paid, which meant that working-class people who depended on a wage could now stand for parliament. In 1894, South Australia was the first Australian colony to grant women suffrage, and by 1902 all white women in Australia could vote and stand for parliament.

However, at the same time, the White Australia Policy restricted the entry of non-European immigrants and represented the subordination of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Not everyone was equal in Australia.

The organised women’s movement in South Australia helped to win the early suffrage. One of the leaders was Catherine Helen Spence, who had arrived in the colony in 1839, when it was 3 years old and she was aged 14. Although always aware of her Scottish heritage, Spence became a strong advocate of South Australia and what she saw as its reformist role. When Spence became a vice president of the South Australian Women’s Suffrage League in 1891, she was 66 years old, and a very well-known figure in the colony. She had come to prominence through her social work with orphans and the destitute, her fiction writing and work as a journalist, and her advocacy of the proportional representation system of voting.

Spence spurred the debate about women’s issues through her novels, including Clara Morison (1854) and Mr Hogarth’s Will (1865).

Education was crucial to Australian egalitarianism. In the 1870s and 1880s, a system of primary schools in the various Australian colonies introduced elementary education and school leaving ages. It was not until the mid-twentieth century that most Australians could also attend high schools, and even then only a small proportion of high-school graduates could go on to university. Around the turn of the twentieth century, for many Australians, public libraries, schools of art, mechanics’ institutes and public concerts were important sources of education and culture, as well as part of the fabric of the new nation’s blossoming towns and cities.