10.3 Movement of peoples

Central to the changes of the modern world was the mass movement of people. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, free migrants and settlers chose to leave their homelands – particularly China and European countries – in the hope of more land and space, and better lives. Destinations ranged from North and South America to European colonies in Africa, Southeast Asia and Australasia. Before the rise of free migration, however, increasingly large numbers of convicts and indentured labourers from Europe and enslaved Africans were shipped to the Americas, starting in the seventeenth century. By the late eighteenth century, slavery was a large-scale global system of unfree labour exploitation in the Americas, South Africa, Mauritius and elsewhere.

Britain shipped convicts to the Australian colonies for 80 years, from the founding of Sydney as a penal colony in 1788 until the end of the convict system in Western Australia in 1868. After slavery was abolished in the British Empire in 1833, schemes to transport indentured labourers from India and China to various parts of the world rose dramatically. Slavery, convict transportation and indentured labour were interconnected systems of unfree labour, and the economic basis of colonies and plantation societies around the world.

Slavery and indentured labour

Slavery, the enforced and unfree labour of some people for others, was practised from ancient times in Rome, Egypt, elsewhere in Africa and other places. When Europeans first sailed to sub-Saharan Africa in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the slave trade there was long established.

Europeans took advantage of this trade, and greatly expanded it as they bought slaves to perform the hard labour of building their colonies around the Atlantic Ocean. Portuguese traders and plantation owners used enslaved Africans in the Azores, Madeiras, Cape Verde islands and Sao Tome, and from the 1530s in Brazil. Spanish settlers and officials introduced slaves into the Caribbean, Mexico, Peru and Central America.

From the early seventeenth century, English settlers imported slaves into their North American colonies. The slave trade provided labour to all of these colonies and was enormously lucrative to the merchants who bought slaves in Africa and sold them in the Americas, then took sugar, tobacco and other commodities from the Americas and sold them in Europe. Conditions for enslaved Africans who survived the ‘middle passage’ across the Atlantic were horrifically cramped and vile.

Work on plantations was back-breaking, and punishment harsh. In the eighteenth century, around 60 000 slaves annually were taken to the Americas. By the mid-eighteenth century, dominance of the slave trade had passed in turn from the Portuguese, the Dutch and the French to the British and the Americans, and the Portuguese who supplied slaves to Brazil.

By the late eighteenth century, humanitarian opinion condemned slavery. The slave trade was abolished by Denmark in 1803, Britain in 1807, the United States in 1808 and Spain in 1845.

Slavery as a system was abolished in British territory (South Africa and the West Indies) in 1833, French colonies in 1848, the United States in 1865 and Brazil in 1888. Centuries of the Atlantic slave trade did much to build the Americas, while it had long-term disastrous effects on Africa.

Indentured labour schemes had brought labourers to the Americas before the system of slavery eclipsed them. As slavery was outlawed in the nineteenth century, indentured labour grew rapidly because indentured workers were paid less than those receiving full wages. Indentured labourers from India, China, Africa and Melanesia were taken by recruiters to pastoral properties and plantations (often sugar) in places ranging from the Caribbean to Mauritius, South Africa, Fiji and the Australian colonies. In Australia, Chinese and Indian indentured labourers suffered high mortality rates, loneliness and racial century, large numbers of Melanesian islanders did the hard work on Queensland’s sugar plantations.

In the early to mid-nineteenth century, indentured labour schemes brought workers to Australia from India and China. Some died, some returned home and others stayed.

Convict transportation

In the eighteenth century in British North America, indentured labour, convict transportation and slavery all coexisted as a means of providing labour from Britain and Africa to the colonies. Up until the American Revolution in the 1770s, the British government sold convicts to shipping contractors, who transported them to the southern colonies in America and the Caribbean, where they were sold to the planters as indentured labourers to work, for example, in rice and tobacco fields. In the first half of the eighteenth century, about 30 000 people were shipped to America in this way.

With the revolt of the American colonies, Britain lost this system and in the mid-1780s British officials cast around for alternatives, considering places like Canada, the Falkland Islands, West Africa, the West Indies and the East Indies. A few men were actually transported to Africa in 1784. This was the context in which the British government decided that the little-explored land on the other side of the globe was the best solution, and to establish penal colonies in Australia.

The system of transportation in the Australian penal colonies lasted from 1788 to 1868. Over the whole period of transportation, the British government shipped more than 160 000 men, women and children to Australia. The convicts were distributed among government, military and civil institutions, as well as settlers, with the government having first choice. Up to 1810, the needs of the government for convict labour were overwhelming. Convicts worked on government farms, built roads and erected public buildings.

In the 1830s, the British government was persuaded by the argument that assignment of a convict to a private farmer was a form of slavery – which they had just abolished. So in 1839 the British government ordered the abolition of the assignment system in both New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land. Then in 1840 it abolished transportation to New South Wales, although it continued to Van Diemen’s Land.

After a large increase in the numbers of convicts in Van Diemen’s Land, settlers there protested and transportation was stopped in 1853. Convicts were still sent to the Swan River Colony (Perth) until 1868.

Not all of the convicts transported to the Australian penal colonies between 1788 and 1868 were political radicals or from the white labouring classes. Perhaps up to a thousand convicts in Australia were slaves, former slaves and free blacks from the Caribbean; free blacks and former slaves from Britain; indigenous Africans sent from the Cape Colony and via Britain; African-Americans; and Malagasy slaves, former slaves, Indian convicts, and Indian and Chinese indentured labourers transported from Mauritius.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 10.2

- List the Australian states that began as penal colonies.

- Research which towns, cities or islands in particular began as penal colonies. During what years did they serve in this way?

- Discover whether your city or town had a convict station or was close to one. If not, did emancipated convicts move there in its early period of settlement? Are there any remains of buildings or other evidence of convict days?

Settlers

Slaves and convicts were shipped around the world by force. Indentured labourers had some choice, but were often compelled by starvation or tricked into entering their contracts. Those who chose to leave their homeland and try their luck in a colony or new country were settlers or migrants. Convicts who served out their terms and chose to stay, and indentured labourers who did not return home, could become settlers.

From the sixteenth century onwards, millions of Europeans spread around the world, including the Portuguese settlers who went to Brazil; the Spanish who went to Mexico, Argentina and other parts of Spanish America; and the Dutch who went to South Africa and the Dutch East Indies. British settlers went first to the North American colonies and the Caribbean, while British merchants also headed to South and Southeast Asia. From the late eighteenth century, settlers chose to make new lives in what would become the settler dominions of the British Empire: Canada, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand. Even more British migrants continued to sail across the Atlantic to the United States, along with immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe, especially in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Canada had both British and French settlers, and came under full British control only after wars in the mid to late eighteenth century. Steps towards self-government in British settler colonies began in in the 1830s in Canada, where the French settlers particularly sought representation.

Like in the United States, European settlement spread across western Canada in the nineteenth century through violent dispossession of First Nations people, along with a vast program of railroad building. More British settlers chose to go to Canada than Australia and New Zealand, partly because it was closer. In turn, more people migrated to Australia and New Zealand than to South Africa, although British colonies in Africa expanded rapidly in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Mobility was key to the modern period. Some migrants returned home to Europe, while others moved on from their first destination.

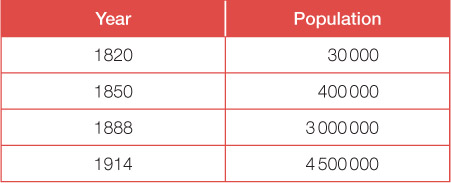

| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1820 | 30 000 |

| 1850 | 400 000 |

| 1888 | 3 000 000 |

| 1914 | 4 500 000 |

Source 10.7 Growth of the Australian population

RESEARCH 10.1

Divide the class into six groups. Assign each group to one of the following countries of origin of migrants: Britain, Spain, the Netherlands, Italy, Ireland and China. Using the school library and the internet, each group is to research the high period of migration from the country of origin, and the migrants’ major destinations. Present your findings to the rest of the class as either a poster or PowerPoint presentation. Be sure to answer the following questions:

- Identify what drove the migrants to move.

- Consider what was happening in their country or region of origin at the time.

- Explain why they chose their major migration destinations.

- Reflect on whether those destination countries still have significant numbers of people of that ethnic group. Why or why not?