10.2 How the Industrial Revolution affected living and working conditions

For those who worked in domestic service or the expanding number of factories, textile mills, mines and breweries, life could be a hard daily grind. Before industrialisation, the household was the centre of production and all members of the family participated in work, including children.

Child labour in factories was therefore not new in and of itself, but the conditions and the hazards for child workers were new. As countries industrialised, the middle classes expanded and there was greater demand for education.

Throughout the nineteenth century, schools grew in number in industrialised countries, and legal requirements were introduced for children to be kept at school until they were 12 or 14. In some poorer and colonised countries, access to education also improved, but in limited ways and often with racial restrictions. In settler societies like Australia, a few Indigenous people attended mission schools, but education was fundamentally for the white settlers.

Industrialisation meant the separation of home and work, with the introduction of workshops, factories and office buildings. It also introduced a new gendered division of work that cast men as the ‘breadwinners’ with the important jobs and main incomes, and rendered women as dependants who kept house or, if they did work, deserving of only low wages. For many working-class women who had to support themselves and their families, this created limited opportunities and real hardships.

Domestic service was a major area of women’s work. Some women ran small businesses like boarding houses and shops; others worked on farms, perhaps with their husbands. Some sewed on machines in factories, or at home in poor conditions, and became known as ‘sweated labour’.

In Australia, industrialisation meant that men worked in tough and dangerous conditions down mines and in factories, and in hard construction labour on roads, buildings, railway lines, water and sewerage pipes, and telegraph and telephone systems. Some men drove drays and wagons; others worked as drovers, shearers and agricultural labourers on the pastoral stations and farms expanding across the continent.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 10.1

Modernity and representation: art and photographs

As industrialisation changed ways of production, the places of production (from home to workshop or factory) and the conditions of work, it also changed the way the modern world was depicted and recorded. The printing press was invented as early as the fifteenth century. In the nineteenth century, cheap newspapers and books revolutionised the flow of information around the world and helped to rapidly raise levels of literacy. From the end of the eighteenth century, lithography enabled the mass production of the older art form of etchings.

From the 1830s, the first kind of photographs, called ‘daguerreotypes’ after inventor Louis Daguerre, enabled what must have seemed the miracle of capturing actual images of people and scenes. Photography advanced and spread rapidly in the nineteenth century. In the early nineteenth century, prosperous families who wanted images of themselves would commission artists to paint portraits. By the late nineteenth century, photography studios sprang up in towns and cities, and people began to have their photos taken – at first in set poses with the background supplied by the photographer.

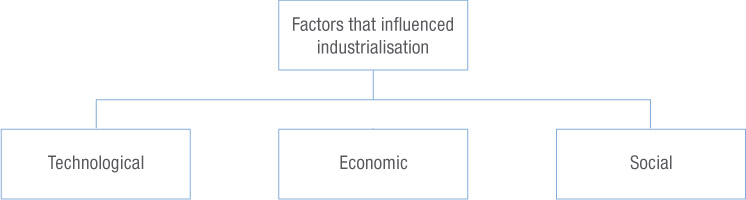

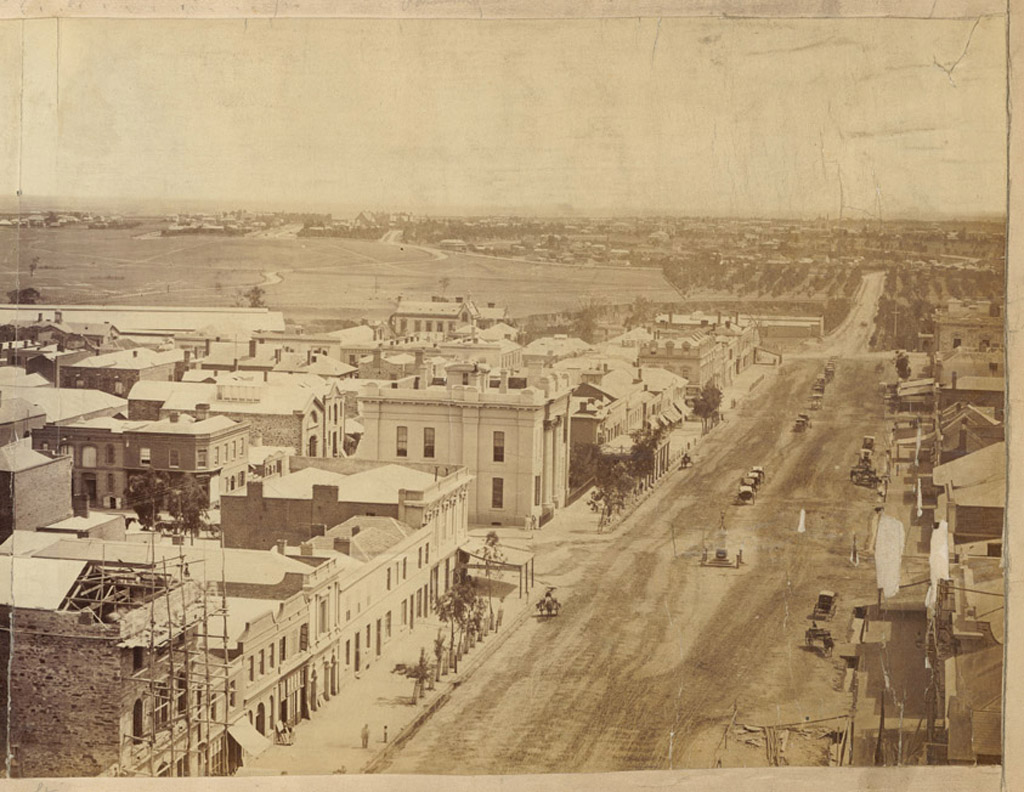

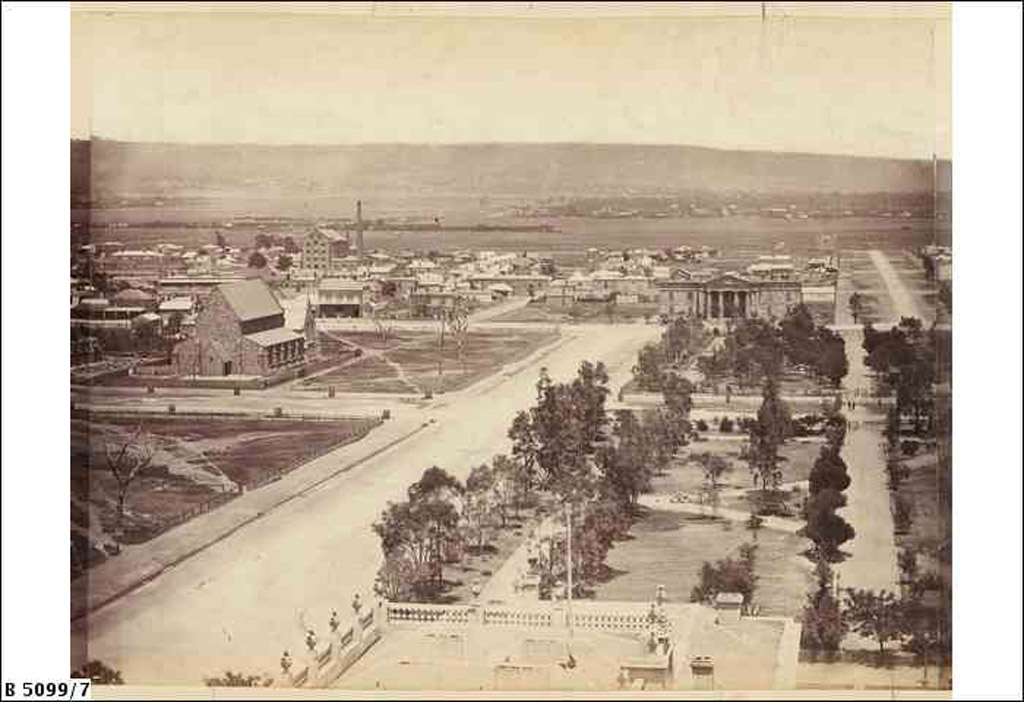

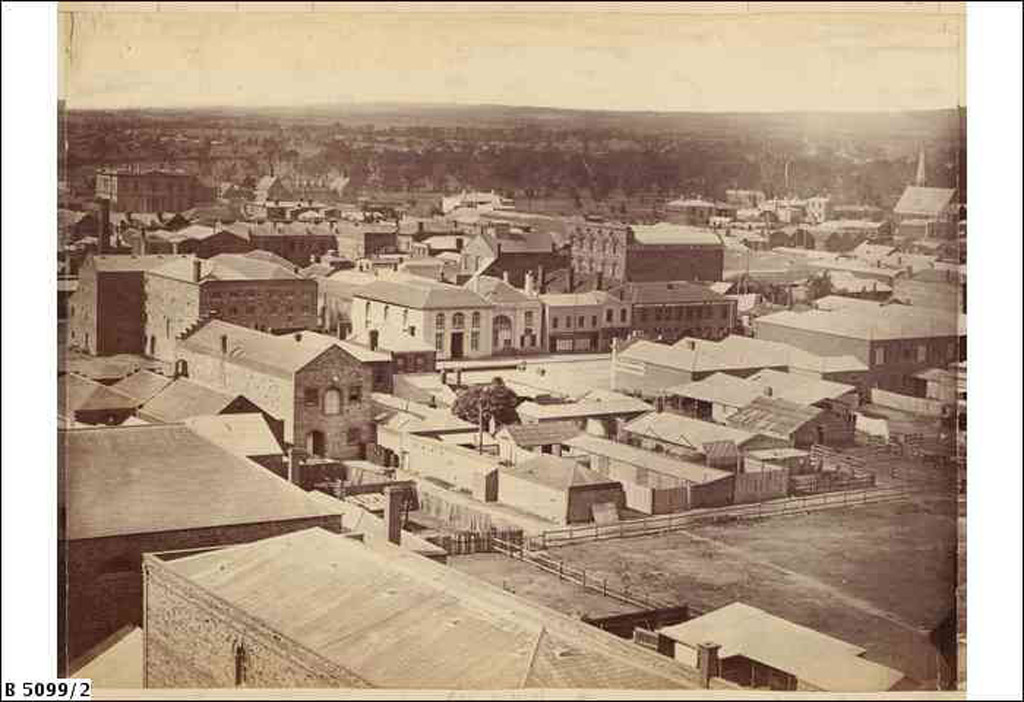

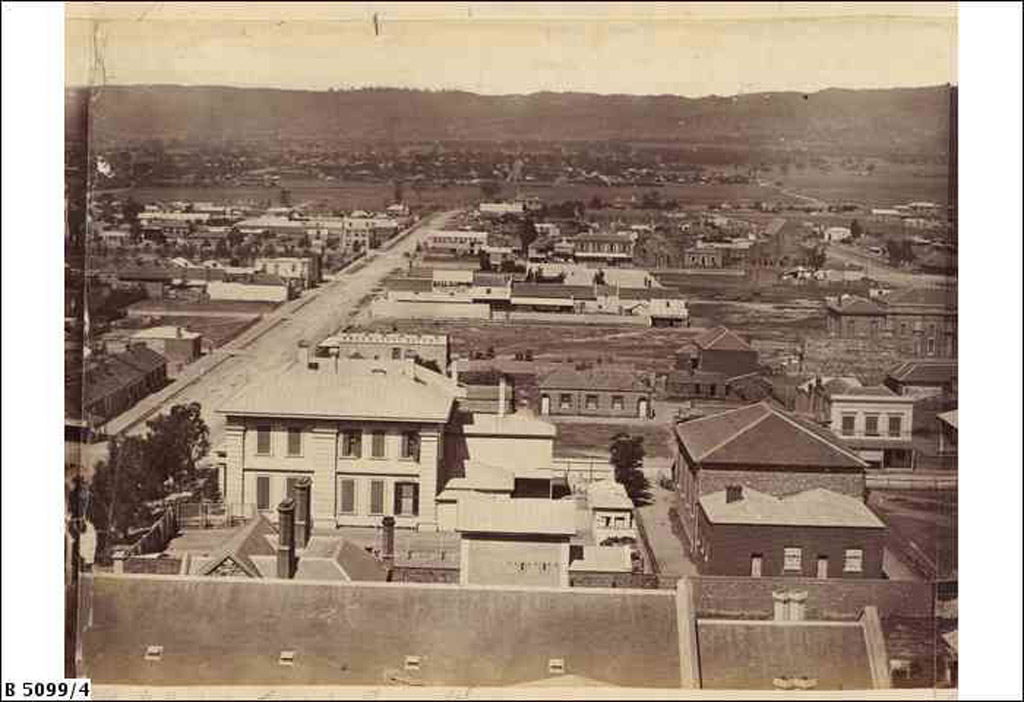

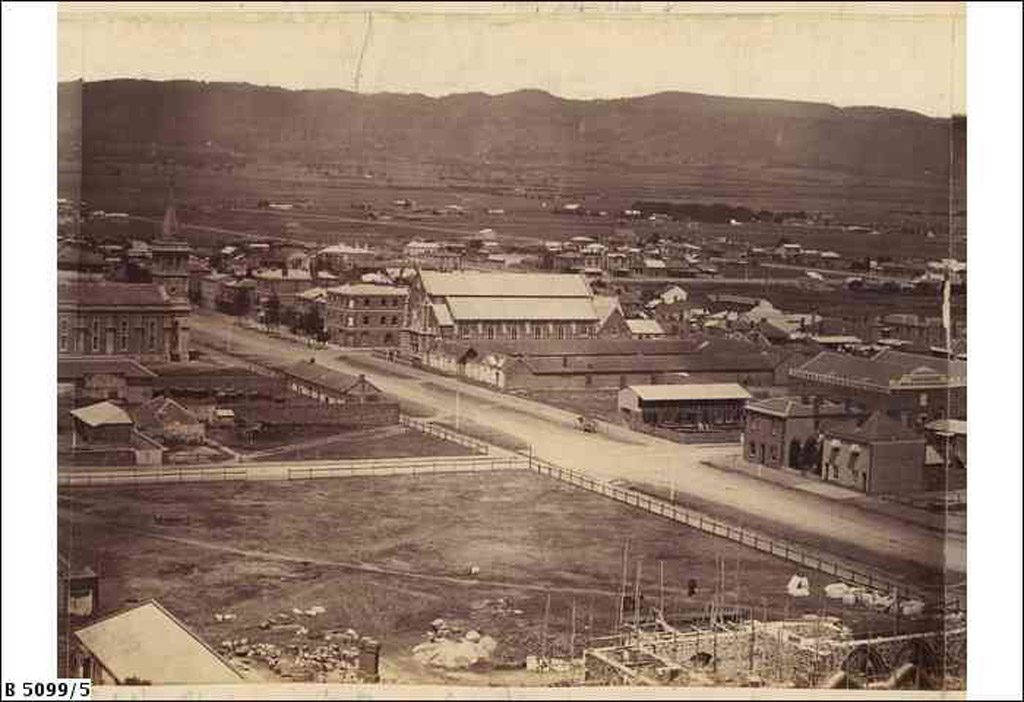

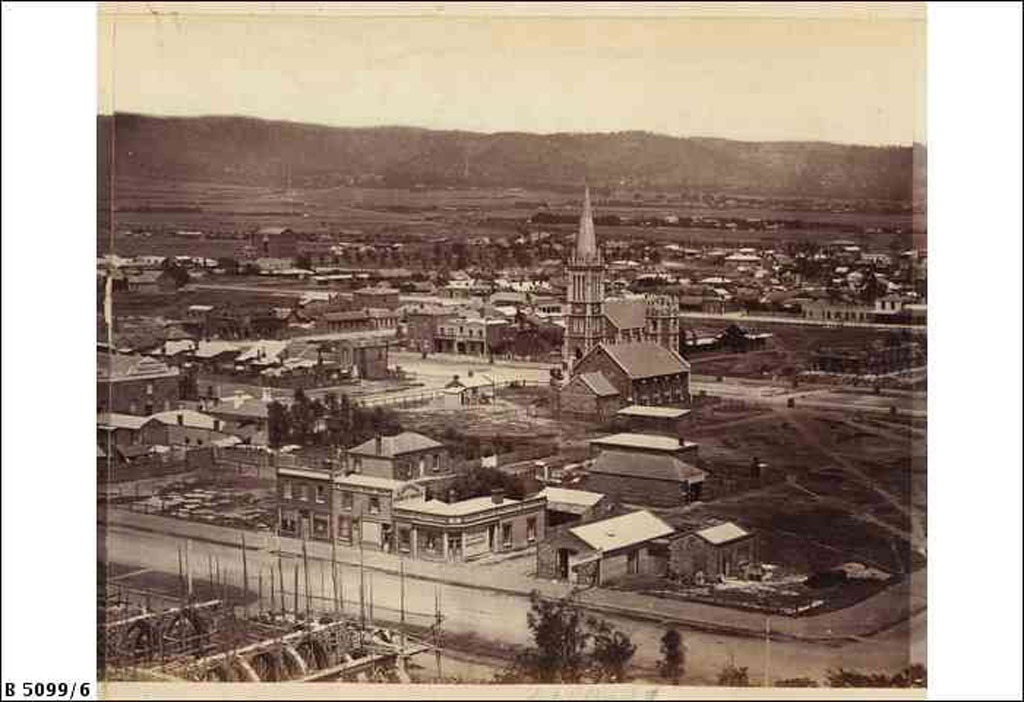

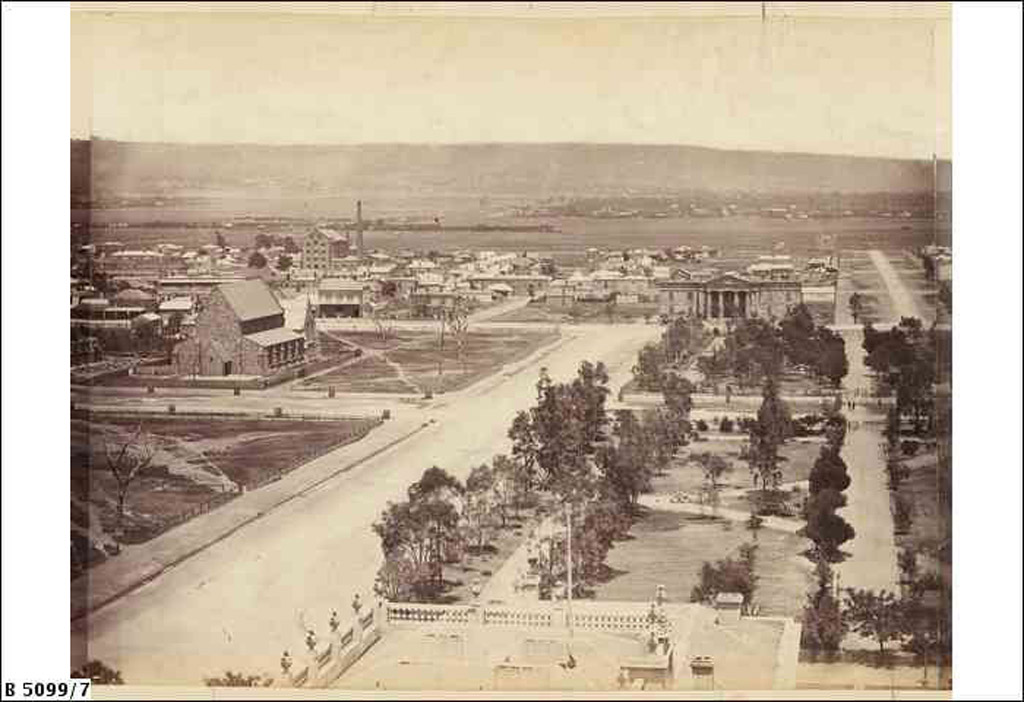

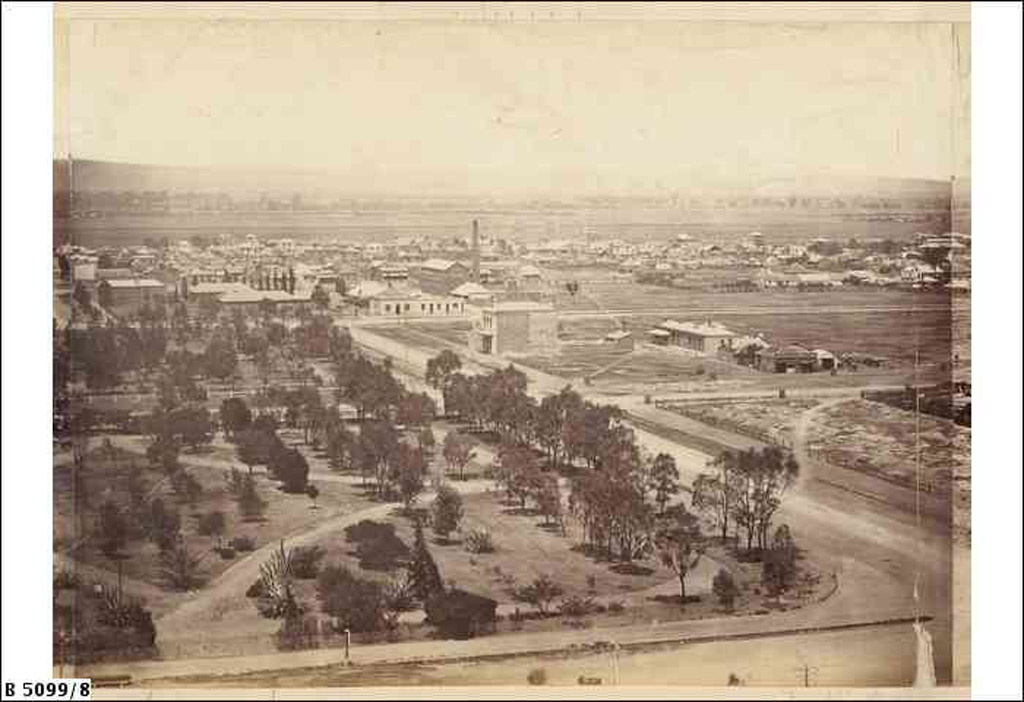

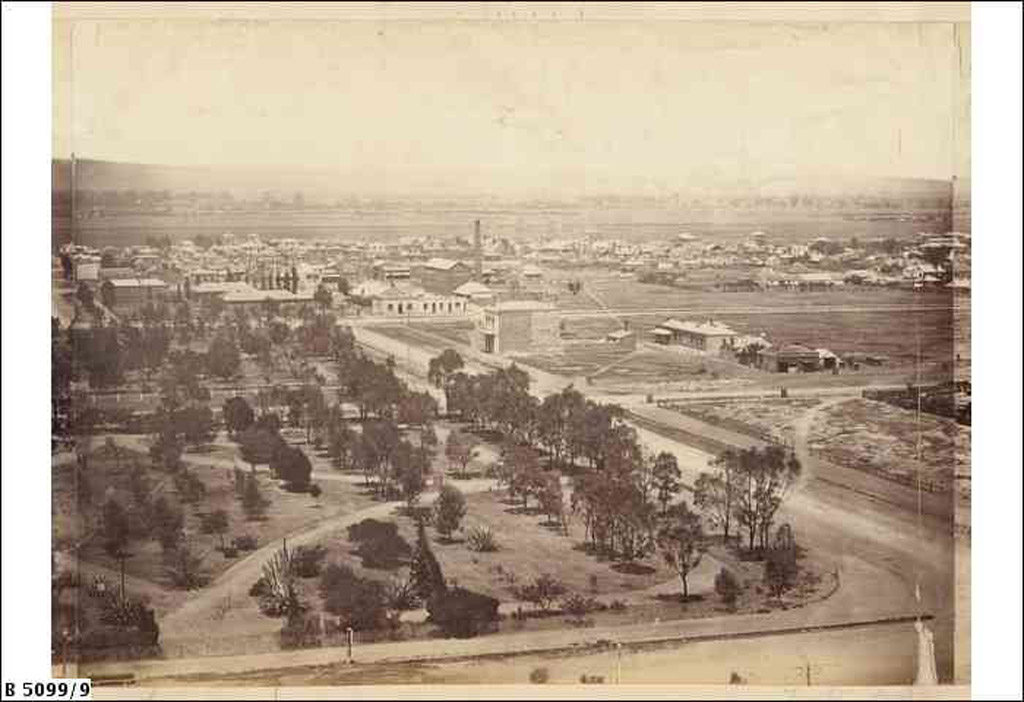

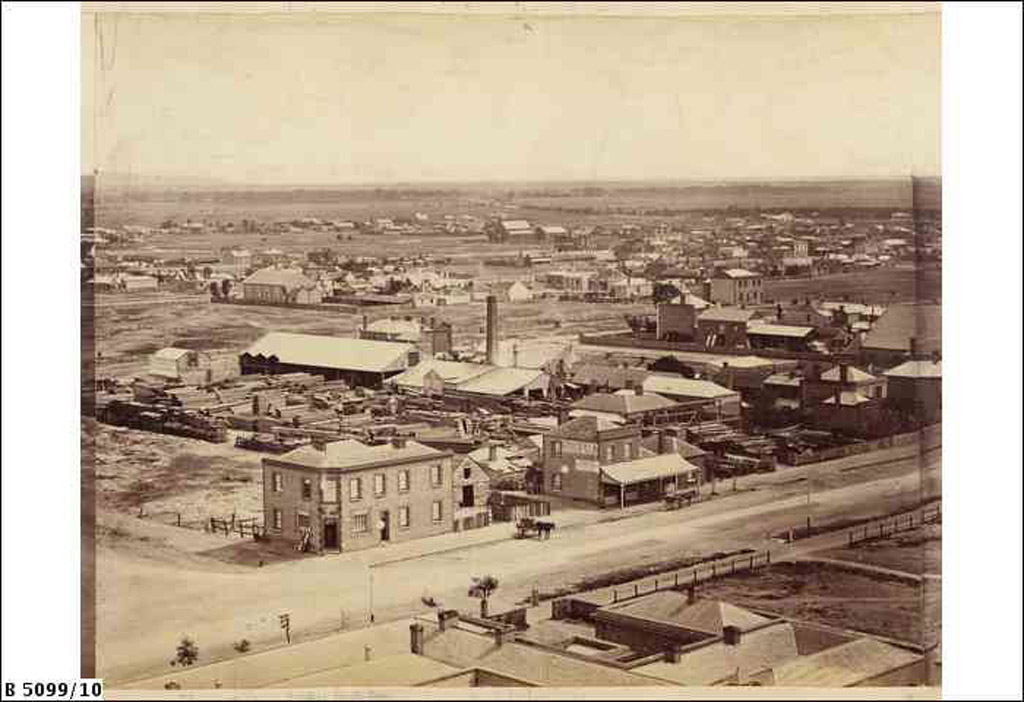

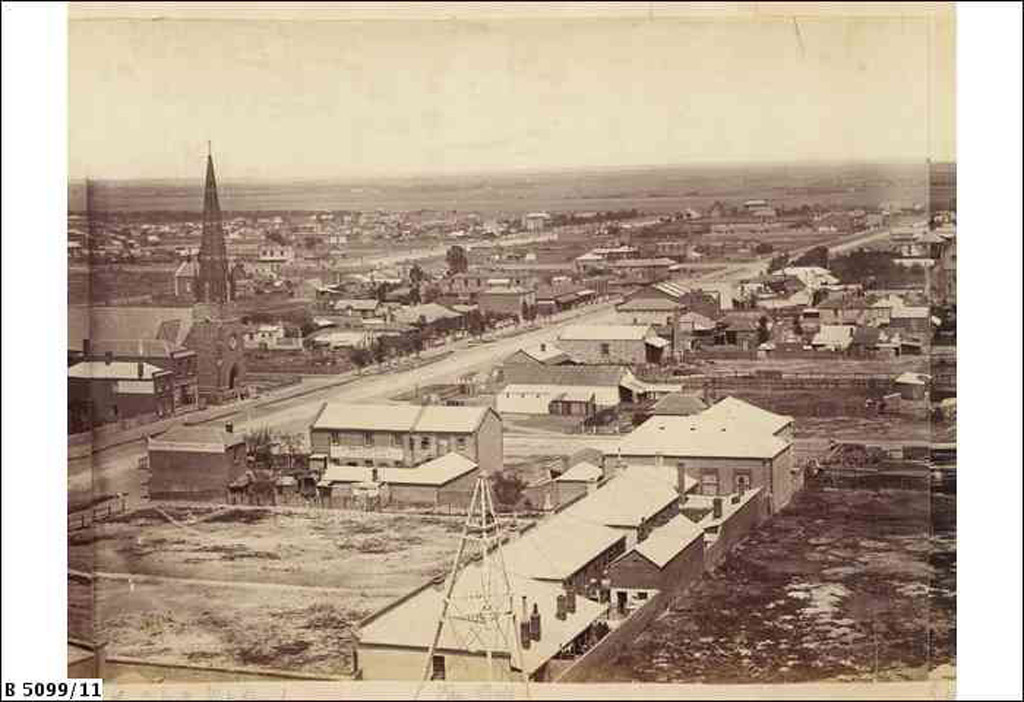

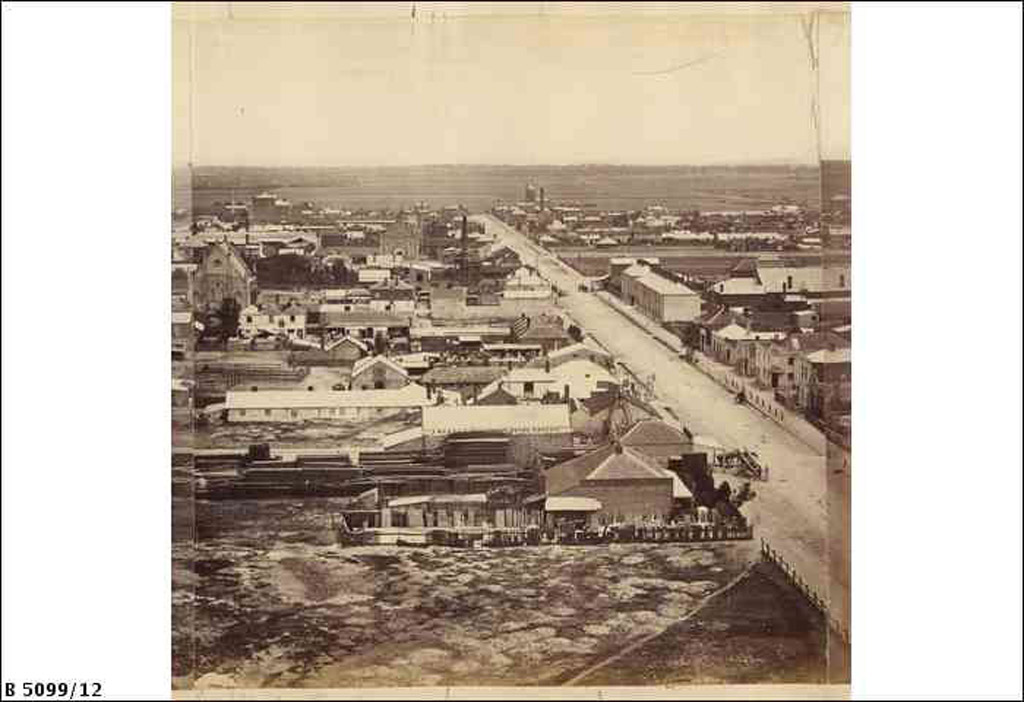

The emergence of photography in the mid-nineteenth century coincided with the rapid development of Australian cities, and the photographic record allows us to see their expansion and changes. A striking example is the Duryea Panorama, a circular series of 14 photographs of Adelaide in 1865 taken by photographer Townsend Duryea (see Source 10.3).

Changing nature of sources and depictions of life

By the end of the nineteenth century, photographs had captured the vast gulf in the standards of living between rich and poor. While they recorded the amazing growth of cities and the rise of bigger and taller buildings, bridges and other industrial triumphs, along with the splendour of the large houses of the wealthy, they also recorded the appalling living conditions of workers. In various industrialised countries, concern about the conditions of life for workers prompted some photographers to record the cramped and unsanitary conditions of poor people living in slums and tenements.

In Australia, painting increasingly became a recognised part of national culture. In the late nineteenth century, artists of the Heidelberg School (a group of painters associated with Heidelberg, which was then just outside Melbourne) and others captured scenes of life in the bush and at the seaside, along with scenes of daily life, especially in and around Melbourne and Sydney.

In the twentieth century, painting and other art forms increasingly recorded and reflected the Australian environment, life and culture.

At the end of the nineteenth century, French brothers Auguste and Louis Lumiere were the first to turn still photographs into the moving world of film. Their first film footage, recorded in 1895, showed workers leaving their factory.

Source 10.4a Auguste and Louis Lumiere’s first film, La Sortie de l’Usine Lumière à Lyon (00:35)

In the early twentieth century, silent films quickly became a huge part of popular culture around the world, with cinemas appearing in towns and cities.

Silent films were often melodramatic, with many featuring aspects of modern life and technology such as cars, trams, factories and bustling cities.

Australia soon had its own film stars, such as the swimmer and diver Annette Kellerman, whose first major film, Neptune’s Daughter (1914), was an international success.

Some of the famous Australian artists of the Heidelberg School, including Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton, produced some of their iconic paintings of the Australian bush in their studios in London. Since the 1850s, steamships had made travel between Australia and Britain faster and more comfortable. Artists often painted from drawings they had made on location.