9.2 Immigration in Australia

Prior to 1788

The first waves of immigrants were the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

They arrived via island and land bridges from the north over 50 000 years ago. As they spread across the continent Aboriginal people developed close connections with the lands that supported them, and ways to communicate the meanings they attached to events and places through language and cultural practices. Passed down through generations of younger Aboriginal people is the notion that their ancestors should be accorded great respect and that this will contribute to their spiritual wellbeing. This layer of occupancy of Australia is best understood through listening to and talking with Aboriginal people in your local area. One of the many important things non-Indigenous Australians can learn from them is the interrelationship between Aboriginal people and their lands: the power of attachment to place.

Colonial settlement, convicts and early ‘free settlers’

Most of the nineteenth century is marked by British colonial influence. Waves of convicts, primarily from the working classes of Ireland and England (mostly London), transported here because the English jails were full, were used as labourers, and constructed the roads, bridges and early buildings for the expanding settlements. The military presence dominated this early period. They were there to guard the convicts and make sure that the grand vision for the settlement created by the politicians back in London was fulfilled. Sydney and Hobart were the first settled colonies; they were followed by Melbourne, Brisbane, Perth and finally Adelaide, which was the first planned and ‘free’ (no convicts) colonial city. All are named after military or political leaders.

By the mid-1800s news of Australia’s rich resources and prosperous lifestyles had filtered back to Britain, and a steady stream of free settlers started to arrive. Access to land attracted farming communities, and mineral wealth soon emerged – gold was discovered. The English, Scottish, Irish and Welsh were the dominant migrants during this phase, but were soon joined by Chinese prospectors and other European migrants, notably from Germany. Each group brought specialities that transformed local landscapes.

German influence in the Barossa Valley, South Australia, dates back to the 1830s. The Barossa Valley is recognised today as a leading wine-producing area, and the local population is largely made up of families of German origin. The names of the towns and local produce reflect this.

With the discovery of copper in the 1840s Cornish miners flocked to South Australia’s Yorke Peninsula.

Soon to be known as ‘Little Cornwall’, the region dominated the copper trade and the Moonta–Wallaroo region became the copper capital of the British Empire.

Population statistics today indicate that the region remains dominated by families of Cornish descent. Celebrations of Cornish traditions such as the famous Cornish pasties are part of that heritage.

Following the end of convict transportation in the 1840s, Chinese workers were contracted as replacement labourers. Many stayed on, and were soon joined by significant numbers of Chinese who sought their fortunes through gold. The gold rushes of the 1850s to 1870s in Victoria especially attracted large numbers of Chinese immigrants. Many Chinese-born people remained after the gold rushes and settled as market gardeners or set up businesses trading in Chinese products.

The twenty-first century

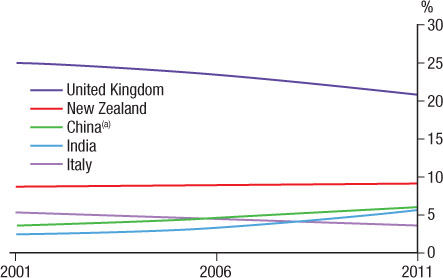

While Australia has remained a land of opportunity and a safe, friendly place to settle, other parts of the world have endured internal conflict, economic hardship and political upheaval. A steady stream of immigrants from troubled regions – including east African countries, the Balkans (including Albania and the former Yugoslavia), Lebanon and Iran, and Chile and Argentina – have sought refuge in Australia. The changing profile of the Australian population is evident in the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS) census data. Source 9.3 shows the region of birth for overseas-born Australians in 2001 and 2011.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 9.3

Refugees

Immigration policy has two major components.

One is the program for skilled workers and families who seek a new way of life in Australia. The other is based on humanitarian aid for refugees and people who are forced to leave their homeland and seek asylum or resettlement in new lands.

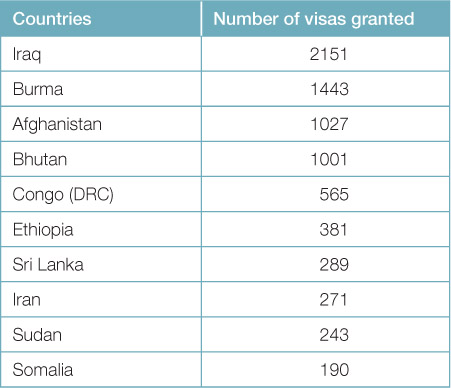

Source 9.5 shows the number of humanitarian visas granted in Australia by the top 10 countries of birth. Notably, in this 2010–11 period ‘women at risk’ received specific attention.

| Countries | Number of visas granted |

|---|---|

| Iraq | 2151 |

| Burma | 1443 |

| Afghanistan | 1027 |

| Bhutan | 1001 |

| Congo (DRC) | 565 |

| Ethiopia | 381 |

| Sri Lanka | 289 |

| Iran | 271 |

| Sudan | 243 |

| Somalia | 190 |

RESEARCH 9.1

One way to grasp the significance of Australia’s changing population profile is to conduct a class census. You can design your own questions along the lines of the official Australian Census (go to www.cambridge.edu.au/hass9weblinks and follow the link to the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ Census at School pages). Questions might include the following:

- What country were you and your parents born in?

- What languages (if any) other than English are spoken at your home?

- How long has your family lived in the place you live in now?

- What other places have you lived (if any) in the last 10 years? Why did you move?

- During the past year, what places did you visit outside your home location?

This list could be pooled and categorised into numbers of visits to relatively close places (local capital city), interstate places and overseas places.

According to the Australian Department of Immigration and Citizenship, in 2010–11 759 visas of the Refugee category were granted to ‘Woman at Risk’ visa applicants, exceeding the nominal annual target.

Multiculturalism

The nation’s most recent policy statement on multiculturalism, from the Department of Immigration and Citizenship (2011), shows the development in acceptance of our cultural diversity. There are four major policy principles:

Principle 1: The Australian Government celebrates and values the benefits of cultural diversity for all Australians, within the broader aims of national unity, community harmony and maintenance of our democratic values.

Principle 2: The Australian Government is committed to a just, inclusive and socially cohesive society where everyone can participate in the opportunities that Australia offers and where government services are responsive to the needs of Australians from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.

Principle 3: The Australian Government welcomes the economic, trade and investment benefits which arise from our successful multicultural nation.

Principle 4: The Australian Government will act to promote understanding and acceptance while responding to expressions of intolerance and discrimination with strength, and where necessary, with the force of the law.

(Source: Department of Immigration and Citizenship)

The transition from the White Australia Policy to the current position on multiculturalism reflects a new phase for a country that is still moving away from its colonial past. While reparation has in part been made to our Indigenous people, there is still a wide gap in health, education and wealth between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples.

There are also challenges ahead with the second generation of immigrants. These minority groups are being integrated into the employment and lifestyle patterns of the modern nation, and there is a sense that all Australians are in a transitional stage of identity. Music, theatre, television, literature, film and painting are all means of self-expression for these groups to contribute to the ongoing evoltion of Australian culture.