5.2 Worldviews

How we identify and interact with a place depends on our individual and cultural perspectives on the relationship we have with the place and its natural and human environmental features.

Perspectives explain how we see the world and our place in it. They include spiritual connections, the values placed on the interdependence of the natural and human environment, our sense of belonging to the place, and the place’s importance through time. The major perspectives and beliefs that determine how we see the world around us and live in it can be called our worldviews.

It is very difficult to fully understand our worldviews because they are so much part of who we are. We usually think, say and do things without realising that we are following our worldview. In a sense, our worldview is to our personal, social and cultural being as our lungs and heart are to our physical being.

It is important to be aware of our and other people’s worldviews – where they come from and how they influence our thinking. Through understanding our and other people’s worldviews we are more able to positively connect with other people and cultures.

An understanding of our own worldview also helps us to better appreciate how we see the relationship between humans and the environment. For example, is it a relationship based on seeing humans controlling environments for human needs, or is it a relationship based on seeing human needs and the environment’s needs as interconnected?

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 5.4

- In groups of three, identify a geographical issue to share your views on. It may be a local issue (such as building a skate park), a regional issue (such as building dams on your local rivers) or a world issue (such as how to reduce poverty in the world).

- Spend 5–10 minutes individually thinking, and maybe recording notes, about your ideas and beliefs on the issue.

- Take turns explaining your ideas and beliefs to the other people in your group – take 3 minutes each. Rotate the roles of speaker, timekeeper/questioner (if needed) and recorder.

- After each person has spoken, the recorder will lead a discussion on the views expressed by the person they recorded.

- Discuss how your views were similar and different, and reasons why this may be so.

Uluru – how worldviews coexist

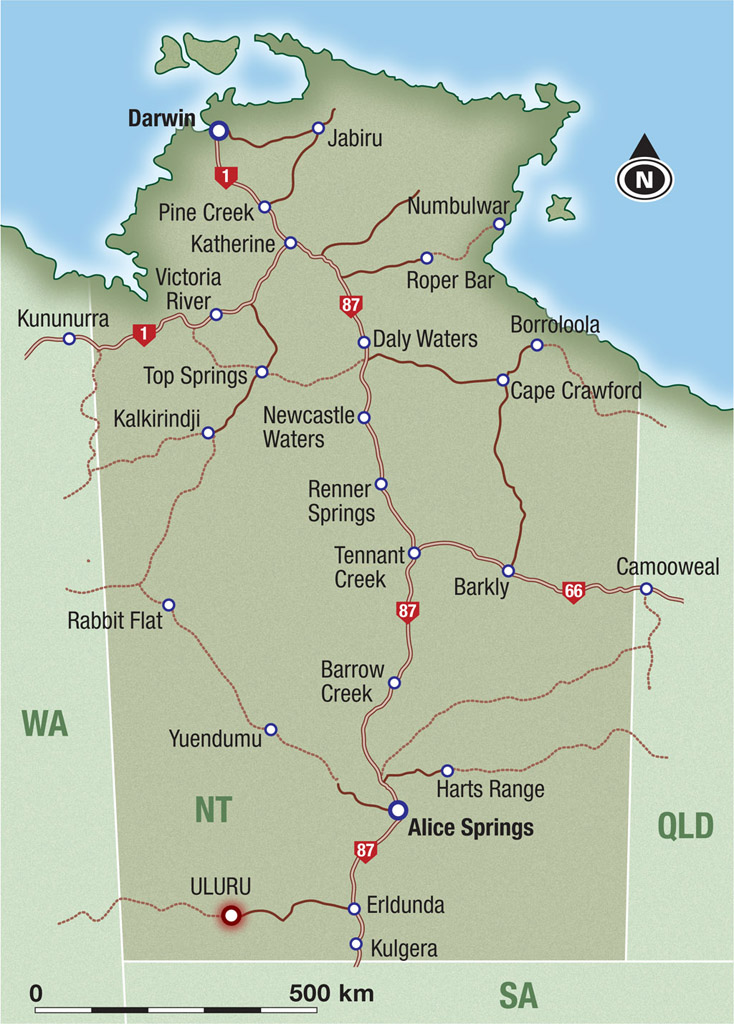

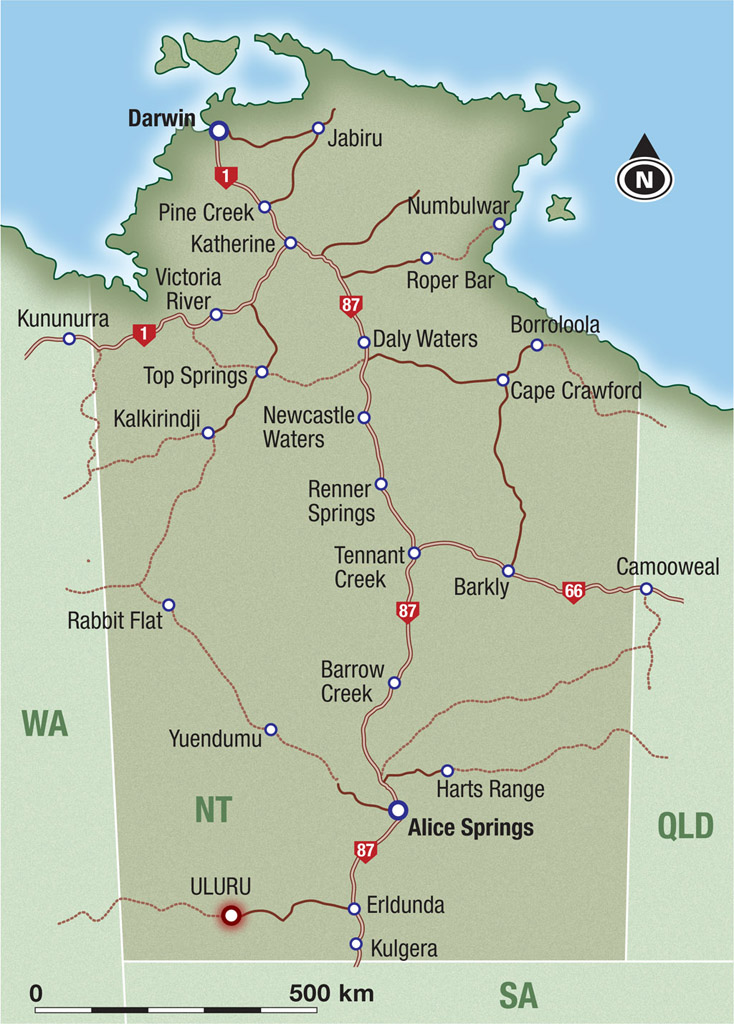

Uluru is an example of how the coming of Anglo/European culture, governance and worldviews to Australia impacted on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s’ connections with country.

The Uluru experience also illustrates how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and Anglo/European cultures and worldviews can coexist. We all have choices about how we do this.

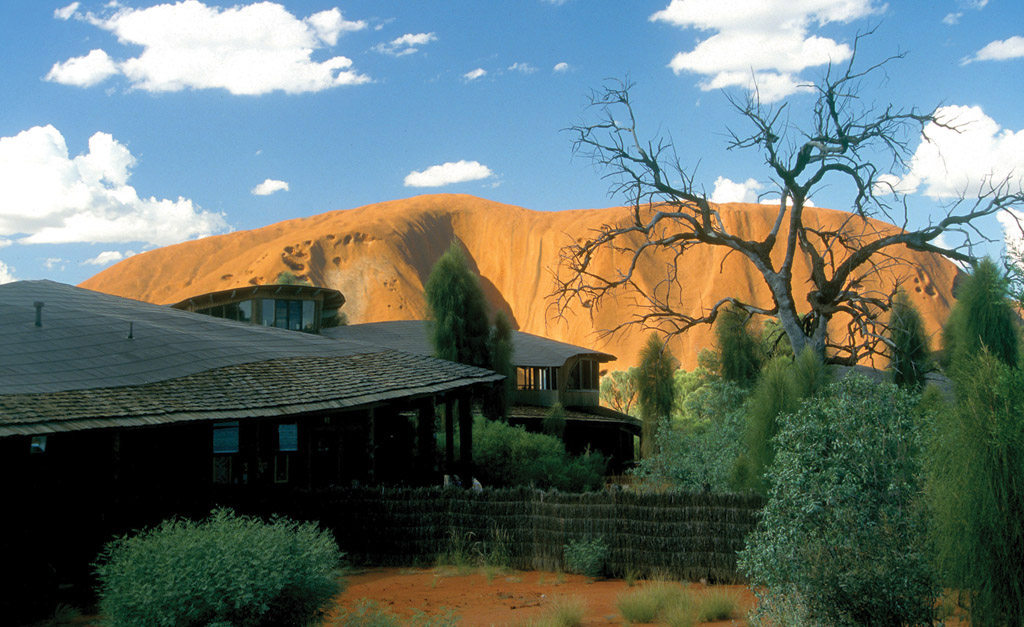

Uluru is recognised worldwide as an iconic symbol of Australia. Uluru and Kata Tjuta have extraordinary cultural, spiritual and geological significance. The Anangu people, the traditional owners of country including Uluru and Kata Tjuta, have lived in deep spiritual and cultural interdependence with this country for tens of thousands of years. They are part of the oldest cultural–country interrelationship still existing on Earth.

Uluru and Kata Tjuta are among the oldest landforms on Earth. Rocks there have been dated at around 550 million years old. Their cultural and geological significance is recognised: Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park was listed as a natural World Heritage site in 1987. In 1994 Uluru-Kata Tjuta was re-nominated under cultural criteria, and it is now recognised as a mixed natural and cultural World Heritage site. It is one of only 29 sites worldwide with this joint listing.

World Heritage listing is managed through the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as part of an international treaty called the Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, adopted by UNESCO in 1972. The treaty aims to identify, protect and preserve sites of cultural and natural heritage around the world that are considered to be of outstanding value to humanity.

The recent management of Uluru-Kata Tjuta country and of tourism in the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park illustrates how people’s different worldviews can coexist.

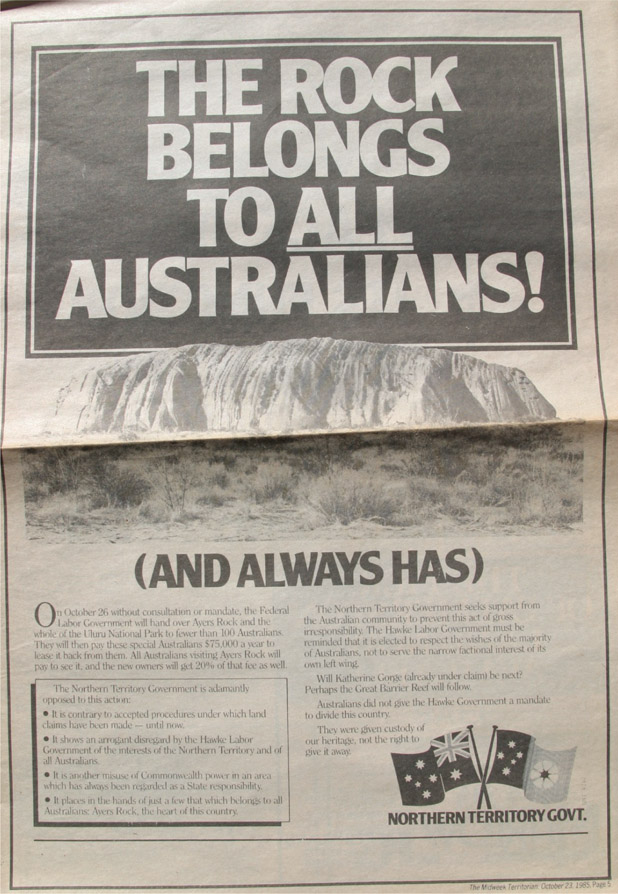

At a ceremony at the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park on 26 October 1985, Sir Ninian Stephen, Australia’s Governor-General, handed the title deeds of Uluru-Kata Tjuta to the Anangu traditional owners under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1976 (NT) (‘ALRA’).

At the same time a lease agreement was signed by the newly formed Uluru-Kata Tjuta Aboriginal Land Trust and the Director of National Parks – it leased the land back to the federal government for 99 years. The agreement formally acknowledged Anangu ownership of the park, and recognised the value of Uluru-Kata Tjuta as a park of national and international importance.

The park is now jointly managed by a board made up of Anangu and piranpa (non-Aboriginal people) members, with their roles and responsibilities set out in both the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (‘EPBC Act’) and the ALRA. The EPBC Act ensures that visitors to the park respect its natural and cultural values, while the ALRA protects the property rights of the Anangu. This process of working together has come to be known as ‘joint management’.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 5.5

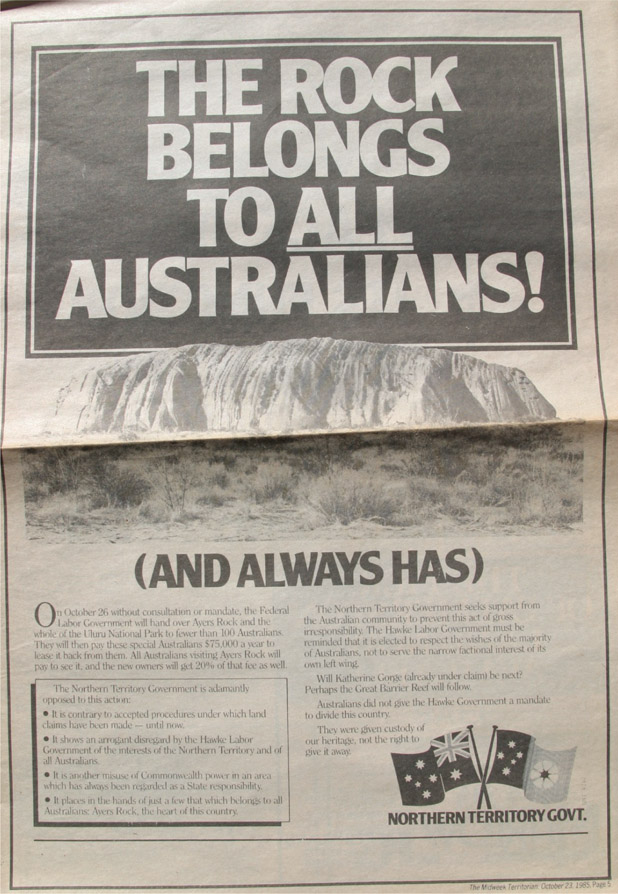

Read the Northern Territory government’s advertisement THE ROCK BELONGS TO ALL AUSTRALIANS! (AND ALWAYS HAS).

- Identify the two main purposes of the 26 October 1985 agreements.

- Explain what the main concern of the Northern Territory government was.

- Identify and justify your point of view on ‘who owns’ Uluru.

- Share your opinions with the class.

Over 400 000 Australian and overseas people visit the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park each year.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people make decisions through consensus. The process is very important. The leader of the conversation is chosen by the community because of their knowledge and skills in the issue being discussed. The people identify the issue and talk about ideas on how to move forward.

Every person tells their story (one story) on the matter. The conversation continues until there is agreement on what will happen.

Non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people usually start by looking at the ‘for’ and ‘against’ arguments of a proposal. The result is often an argument rather than a conversation, and many times a few people dominate the argument.

For many people, the outcome is more important than the process.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 5.6

World heritage sites

UNESCO has listed over 900 locations as World Heritage sites. They are places that have special cultural or physical significance, not just for the local community or the nation where they are located, but for all of humanity.