4.3 The changing nature of Australian agriculture: 1970 until the present

Since the beginning of European settlement, agriculture has dramatically changed both the Australian landscape and people’s relationship with the land. The first 180 years of agriculture in Australia was a period of expansion and consolidation, and patterns of land use became firmly established.

By the 1970s the general pattern of Australian agriculture was predominantly the family-owned farm, which was passed on from generation to generation. The family lived and worked on the farm, and bringing up a family ‘on the land’ was seen as a healthy and attractive lifestyle – money was good, the work was hard but rewarding, and children could be brought up in a healthy environment. Government support for agriculture during most of the twentieth century was strong, and state and federal governments provided incentives for farmers to produce more. They spent vast amounts on agricultural infrastructure such as irrigation schemes and set up trade barriers to protect Australian farmers from offshore competition. The world demand for Australian farm produce was high and farmers got good prices for staple commodities such as wool and wheat. Within Australia food-processing factories such as Rosella, SPC and Arnott’s Biscuits were processing Australian farm produce into a variety of goods – tinned soup, fruit and biscuits – and Australian consumers were really only offered ‘Australian made’.

-

Source 4.29 Australian food-processing companies such as Rosella process the products of Australian farmers. -

Source 4.30 Along a 1-kilometre stretch of suburban road in Coburg, in Melbourne’s north, which was developed in the 1920s and 1930s, there were about a dozen of these small shops that serviced the local community with fresh produce such as milk, eggs, fruit and vegetables sourced from the local region. Now these shops have been converted to housing.

Throughout Australia the fresh produce and processed foods of Australian farmers were sold through small businesses – grocery stores, butchers, greengrocers, dairies and corner shops – rather than through the big supermarket chains that we have today. This was a period when there was a much closer relationship along the food and fibre chain between the farmer, the storekeeper and the consumer.

From the 1970s onwards the nature of agriculture in Australia changed significantly and farming became more complex. Changes in national and global economies put pressure on farmers to become more competitive. Today, farmers compete more with overseas producers than they ever did before. The costs of running a farm have soared. Fuel and other farm input costs – such as fertilisers and labour – have risen and competition for limited resources such as water have forced the introduction of such things as water trading, which means farmers have to buy and sell water for their farms.

In the last 40 years Australian cities have expanded dramatically, and increasing numbers of people seeking a ‘tree change’ are moving away from cities into the country, encroaching on farming land and forcing significant change on traditional farming communities within 100 kilometres of the major urban centres, such as by driving up land prices. Other pressures being felt by farmers come from competing land users such as the mining and coal seam gas industries, which are threatening the viability of a number of farming communities – farming land is either being used for the extraction of minerals or is under threat from pollution, such as groundwater contamination associated with coal seam gas production.

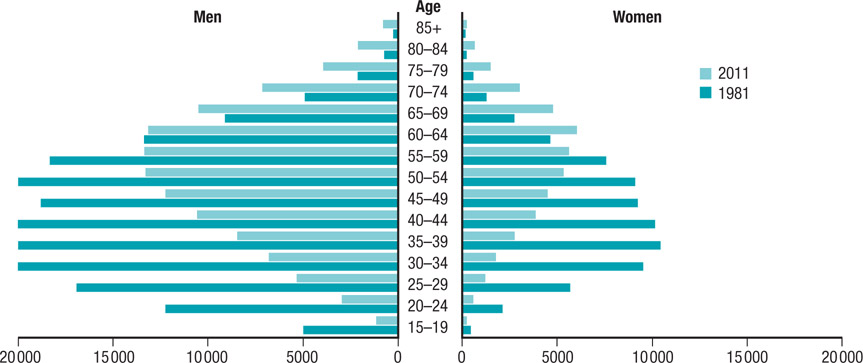

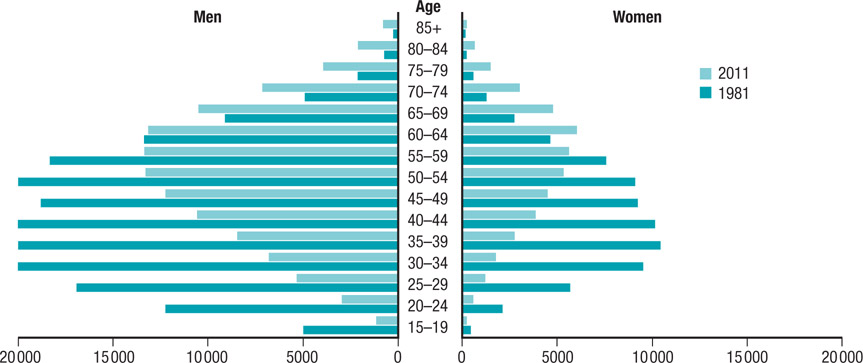

The changing nature of agriculture in Australia is changing the business structure of farming. While the family-owned farm is still the dominant form of ownership in Australia, particularly in industries such as dairying and horticulture, the structure of farms is changing. Since the 1970s the declining profitability of farming has meant that the traditional pattern of farm ownership is no longer economically sustainable. Studies have shown that in some regions of Australia only 28% of farms are of a sufficient size and profitability to support the families owning them. Over the last four decades Australian farmers have faced a decline in the average terms of trade of about 2% per year. What this means is that farmers have had to increase their output by 2% each year just to be able to buy the same bundle of goods and services from year to year. In this environment small farmers are finding it hard to compete and are either leaving the land or being forced to supplement their farm income through employment off the farm. Compared with 1980, there are now 100 000 fewer farmers and the average age of farmers is increasing; many children of farmers decide not to take over the farm when they reach adulthood, so their parents stay working the farm. The sons and daughters of farmers are increasingly leaving the land to find employment in the larger urban centres and the capital cities.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 4.9

- Explain how buying ‘Australian made’ produce assists Australian farmers.

- Suggest why Australian governments might have put tariffs on food imported from other countries to make them more expensive.

- Discuss how ‘tree-changers’ – people moving out of urban areas to live on small rural properties – have affected farming in the areas they are moving into.

The changing nature of rural communities

Rural society is changing. Where country towns once were thriving communities with strong populations and profitable businesses that served the farming sector, many are becoming more like ghost towns, as businesses have closed down and people have left to find work in urban centres.

One such measure of the changing demographic profile of these towns is the death of sporting clubs such as Australian rules, rugby league, cricket and netball – there are just not enough young people to field teams.

Since the 1970s farming operations have become increasingly less geographically and demographically defined as a block of land on which the family has a home and everybody in the family is involved in the running of the farm.

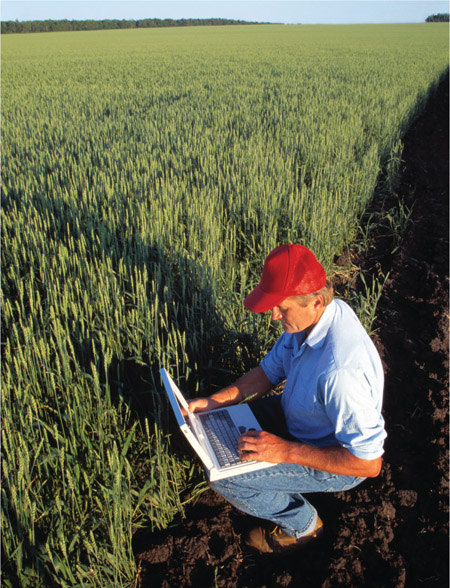

Farmers have become more sophisticated in their approach to the business of farming. The image of the lone farmer working the field on his tractor or rounding up the sheep with a couple of sheep dogs and then trucking the produce off to the local railway siding to be sold is now outdated.

Today’s farmer is more likely to be studying the internet for weather reports, programming the GPS in the tractor to ensure optimum crop planting or negotiating the purchase of seeds for the following year’s crop on a mobile phone.

-

Source 4.32 The rural town of Terowie in South Australia’s mid-north has suffered a dwindling population since rural industries and services went into decline. -

Source 4.33 A farmer using a laptop to input data relating to his wheat crop

Agriculture in Australia today

Modern farming requires an understanding of the whole business of agriculture, from balancing the nutrient levels in the soil to buying and selling water and monitoring international market prices for agricultural commodities.

One way for farmers to remain profitable is to set up smaller-scale corporate enterprises where farming families join together as a cooperative.

These enterprises use economies of scale to deal with rising costs.

The benefits of a cooperative are:

- It can share resources such as farming machinery.

- It is more able to buy resources such as seed and fertiliser in bulk quantities and thus negotiate for a reduction in the price.

- It is better able to negotiate with buyers for optimum return on their products.

- It can more easily afford the services of agricultural consultants who can provide the members of the cooperative with specialist advice.

Another feature of modern agriculture in Australia is the increasing number of large corporations and multinational companies that are investing in agricultural and food-processing enterprises.

Agricultural companies are not new to Australian agriculture; they have been involved since the early period of European settlement.

The Australian Agricultural Company, which today is a major beef producer in northern Australia, was first formed in 1824 by an Act of the British Parliament in order to purchase 1 million acres of land in New South Wales for agricultural production. Its investors included members of the British Parliament and prominent English bankers.

Modern agricultural corporations include large family-run farming businesses that produce a diverse range of commodities on multiple sites.

One such family enterprise in Queensland has 11 farms, stretching 1500 kilometres across a region. This business produces a range of vegetables which it sells to the major supermarket chains. The benefit of this type of business over other farms that are geographically limited and only focus on a few commodities is that, if one commodity is affected by localised weather conditions such as flood or drought, or a downturn in the market price, other parts of the business that are not similarly affected can maintain profitability.

Other enterprises that are becoming more established in Australia are large companies made up of shareholders who are not necessarily farmers.

Some of these companies, such as Timbercorp, take advantage of government tax incentives to buy up substantial areas of land to produce a single crop, such as almonds. These companies have large amounts of money to invest, and have at times dominated the water trading market in irrigation zones, to the detriment of smaller farmers who miss out on their water allocations.

These investment companies are also driving up land prices, so they are seen by many people in the country as not really caring about farming communities and being driven only by profit.

Another feature of modern Australian agriculture is the increasing numbers of foreign companies that are investing in agricultural properties, businesses and food-processing companies. This increase is fuelling anxiety in the bush that Australia is ‘selling off the farm’ and thus undermining its capacity to feed itself if the country hits troubled times. As Barnaby Joyce, a federal National Party politician, put it in 2009:

Overseas interests are targeting our mining and agricultural industries because they have long-term strategic value and we should be mindful of that. We are not going to be able to sustain ourselves in the long term through service industries; that is the economic form of trying to make a living by taking in someone else’s washing. (The Australian, 24 April 2009)

The other concern for farmers in Australia is that foreign companies that have bought food-processing factories in Australia have been shutting down these factories because of the cost of production in Australia. Rising labour costs and the fluctuating value of the Australian dollar have meant that for many of these businesses, which have factories all over the world, it is cheaper to close their Australian factories and produce their goods in other countries.

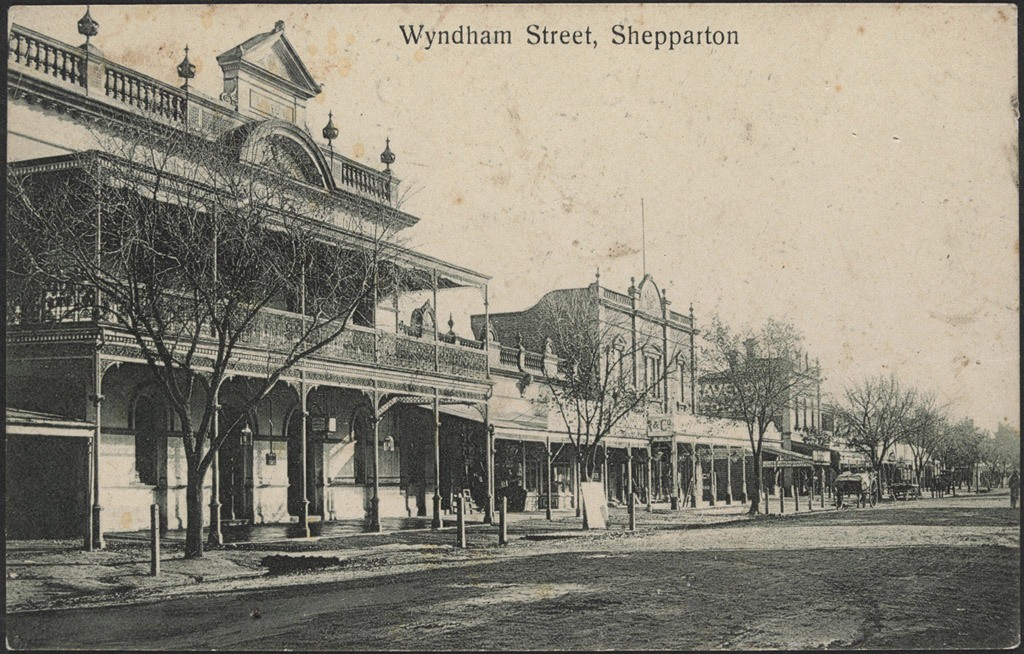

These decisions impact on farmers when they are no longer able to sell their produce to the local processors, and they have a flow-on effect on the economic health of rural communities. Places like Shepparton, in Victoria, have been hit hard by such closures. The SPC Ardmona factory in nearby Mooroopna, which was owned by the Coca-Cola Company, closed down in 2011. SPC Ardmona processed fruit such as peaches and apricots from local growers. Its closure meant not only that people in the factory lost their jobs, which impacted on the regional economy, but also that the local growers had to find other markets for their produce.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 4.10

- Explain how economies of scale might be applied in modern farming.

- It has been claimed that the demise of rural sporting clubs has heralded the death of the soul of rural communities. Explain what you think this means.

- Source 4.31 indicates that there were substantially more people involved in farming in the age group 15–29 in 1981 than in 2011. List some of the reasons for this decrease.

- Explain why the average age of farmers is increasing.

- Explain what the expression ‘selling off the farm’ means.

- Analyse why the buying of Australian farms by foreign companies is such a contested political issue in Australia. List some of the benefits of foreign investment in Australian agriculture.

RESEARCH 4.4

The power of the major supermarket chains – Coles and Woolworths

One of the features of the changing nature of modern agricultural enterprises in Australia is the growing power of the two major supermarket chains, Coles and Woolworths, to influence the prices of agricultural produce. The two chains have been involved in a price war to capture customer loyalty. Each is trying to sell its produce at the lowest prices. This is good for the customers, but is it good for the farmer as well? For farmers who have a guaranteed contract with the supermarkets to supply the produce it could be seen as a good thing, because they are assured of a market for their produce. In the short term the supermarket customers are also benefiting through lower prices for basic food items such as bread and milk.

However, there are growing concerns about the effects this dominance has on Australian agriculture:

- Growers are forced to bid against one another and the successful ones are often the corporate farmers with better economies of scale. This pushes the smaller producers out of the market.

- The farmers who are under contract to the supermarkets have their profit margins reduced. In the case of some dairy farmers, the pressure to ensure that the cost of milk to consumers remains low means that the price they receive for their milk barely covers the cost of producing it.

- Farmers lose autonomy and flexibility over their operations as they are forced to respond to the terms of their contracts with the supermarkets. One of the concerns is that the supermarkets may be making the decisions about how the commodities are produced and what is grown.

- The high quality requirements of the supermarkets for the produce, such as having fruit of an even size and colour, can mean a high use of agri-chemicals.

- Over the longer term, forcing some growers out of the industry could lead to reduced competition pressures, so the supermarkets could in the future start charging higher prices for produce while still keeping their costs low. This would increase the profits for the supermarkets.

Source 4.35 The two big supermarket chains, Coles and Woolworths, have been involved in a price war, bringing down the price of staple food items such as milk and bread. - Supermarkets, in favouring certain types of produce over others, reduce choice and thus may make some types of produce uncommon or not available, leading to a loss in agricultural diversity.

- Supermarkets trying to ensure year-round supply of fruit and vegetables encourage the greater energy expenditure needed to either grow food in artificial conditions or to transport food over great distances.

Sustainable agriculture

Agriculture in Australia has changed dramatically, particularly in the last 60 years. Some of the drivers of this change have been a real need for increased production because of population growth and an ideology that says that progress and productivity are intrinsically good things. In basic terms, for farmers this means making two blades of grass grow where one grew before. As we have seen, food and fibre production and distribution soared through most of the twentieth century, through technological and scientific developments; the expansion of agricultural enterprises and supporting industries, such as the chemical and seed industries; and increased land clearing.

These developments have allowed farmers – and there are now fewer of them – to maximise productivity and reduce their labour costs (by getting more machines to do the work) at the same time.

Although these changes have had many positive effects, including the almost quadrupling of crop yields in some cases, and have reduced many risks in farming, such as dealing with the unpredictability of Australia’s variable climate, there have also been significant environmental costs and social costs.

Environmental costs include:

- land and water degradation

- pollution

- biodiversity loss

- increased energy consumption of nonrenewable sources such as oil.

Social costs include:

- economic decline of rural communities; greater unemployment means less money being spent in country towns

- reduction in the rural workforce as people leave the country to work in the cities

- relative decline in the wages of farm workers

- ageing population of the farming community.

Coupled with these costs are the threats that a changing climate poses to future agricultural productivity. There is a possibility that current agricultural regions will become unsuitable for the type of farming that is currently being practised there.

Over the past 20 years there has been increasing concern that current forms of agriculture are not going to be sustainable over the longer term.

As a result, there is a movement towards more sustainable agriculture. This is based on the principle that we must meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs.

Sustainable agriculture requires an understanding of the relationship between agriculture and natural ecology and the management of that relationship. Sustainable agriculture will:

- satisfy human needs for food and fibre

- enhance the quality of the environment so that it supports natural and agricultural processes, leading to healthy soil, stable landforms, clean water and greater biodiversity

- make the most efficient use of non-renewable resources such as oil

- reduce chemical use and integrate natural biological cycles and controls into agricultural practices (such as using farm-friendly insects to control pests)

Source 4.36 There is increasing consumer demand for free-range chickens because of concerns about the inhuman treatment of caged birds. - ensure that farming operations are economically viable and support prosperous rural communities

- encourage the ethical treatment of animals and abandon high-density practices such as cage-breeding chickens

- enhance the quality of life for farmers and society as a whole.

Responding to the need for sustainable agricultural practices

Australian farmers and rural communities have always been resilient, resourceful and innovative.

Today’s farmers are dealing with the environmental consequences of 220 years of Australian agriculture and the impact of restructuring in the agricultural sector over the last 40 years in a number of ways:

- Farmers are now taking steps to rehabilitate the land through the assistance of organisations such as Landcare Australia, which provides advice and assistance to farmers. One of the ways to rehabilitate the land is to return areas of properties to natural habitats. This promotes biodiversity, and the natural vegetation helps return the water table to manageable levels so that salinity can be kept in check.

- There is better management of irrigation water allocations in river systems such as the Murray–Darling, which helps ensure that there is adequate water for environmental flows which keep the river system and the wetlands healthy.

- Natural wetlands are being restored: they act as buffers, intercepting sediment and nutrient flows in the rivers and streams so that water quality is maintained.

- There is a growing awareness of the value of the native food or ‘bush tucker’ industry as a sustainable industry.

- There is a growing understanding of the use of fire to keep native grassland areas in Australia’s arid and semi-arid zones healthy and provide sustainable fodder for the cattle industry in these regions. These were practices developed by Indigenous Australians over thousands of years prior to European settlement.

- There is increased development and use of organic farming methods – such as crop rotation and recycling of nutrients such as compost – in which no synthetic chemicals are used.

- Farmers’ markets, where smaller producers sell their products, are growing in number and popularity. These markets offer consumers the opportunity to have closer contact with the producers of the foods they eat.

- Rural towns are becoming more resourceful in attracting people into their communities by promoting them as tourism destinations, and through niche industries. For example, Clunes, a rural community in central Victoria, promotes itself as a destination for book lovers, and its annual book fair attracts hundreds of visitors.

Thomas Malthus was an eighteenth-century economist who predicted that human population increase would eventually outstrip food production and lead to a natural check on population growth through famine, disease or war. Malthus’ argument, which he put forward in his Essay on the Principle of Population in 1798, was that population growth increases exponentially, so it doubles with each cycle (1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32 … and so on) while agricultural production increases arithmetically over time (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 … and so on). Malthus’ theory is just one of many about the relationship between human growth rates and the ability of agriculture to sustain human populations. His gloomy projections haven’t been fulfilled – yet, at least – even though the world population reached 7 billion in 2011.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 4.11

RESEARCH 4.5

- Investigate the role of Landcare and other conservation organisations in Australia that assist farmers in managing land and water.

- Research genetically modified crops. Analyse whether or not they have a place in sustainable agricultural practices; list some of the arguments for and against them. Present your findings to the class in a PowerPoint or Prezi presentation.

Food security

Apart from the early period of European settlement at the end of the eighteenth century, when the colony almost starved, Australia has managed to provide the food and fibre requirements of its population and have a surplus to export. Today Australian farmers produce over 90% of Australia’s daily domestic food requirements and approximately 60% of their total agricultural production is exported. In the global market Australia contributes 1% of all food consumed in the world and feeds about 40 million people outside Australia each day.

Australian agriculture has always been at the leading edge of innovative practices and technological advances, and it must maintain this position if it is to continue to provide food security for both Australian and global communities. The population of Australia is projected to grow from almost 23 million in 2013 to 35 million in 2050, and the global population is projected to grow from 7 billion in 2011 to 9 billion in 2050, so the pressure to increase agricultural productivity is enormous.

This will also be influenced by the predicted effects of climate change.

Until now, Australia’s food security has been maintained by the availability of:

- arable farming land

- affordable energy resources

- water

- nutrients

- effective farming and trade practices

- efficient transport networks

- sufficient storage capacity for agricultural products.

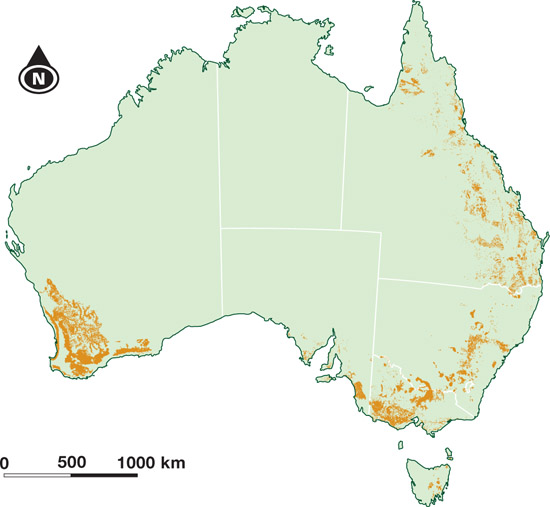

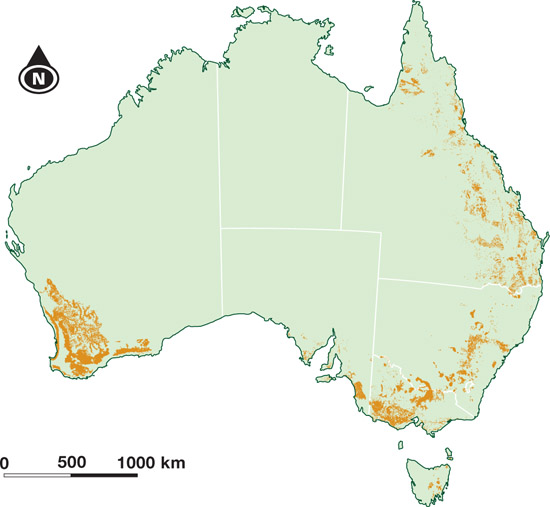

Climate change is expected to have a significant impact on everything on the list above. Current projections are that in Australia we can expect changes in both the distribution of water available for agriculture (such as river flows) and the timing and duration of rainfall events. Higher average temperatures will increase evaporation rates and reduce moisture levels in the soil. If rainfall, water distribution and temperature patterns are altered, land use patterns will change – production may decline in existing agricultural areas.

Climate change projections also point to an increase in the frequency and intensity of adverse weather conditions such as flood and drought, and suggest changes in the geographical distribution of pests and diseases. This combination will make the production of some cereal crops and livestock unsustainable at some locations. Widespread adaptation, including the relocation of existing agricultural regions, will be required. Also, many existing farming practices will need to change to meet the requirements of reducing carbon emissions and restoring land and water health.

The capacity of the world’s natural resources to deal with increasing human population is going to be stretched to the limit in the next 40 years.

Currently, human activities use one-third to one-half of the global ecosystem’s production; that is, looking at all the things that the Earth’s processes produce, such as fresh water and biomass (crops, for instance), humans are taking 30–50% of it for their own use. To extend this beyond 50% is going to put enormous pressure on the biosphere.

A roadmap for the future of agriculture

Greater management of both natural and agricultural resources is going to be needed if we are to secure food production over the next 40 years. Some of the strategies required are:

- protection of existing natural ecosystems to ensure the health of natural processes and maintain biodiversity: this means reducing the current rate of land clearing

- restoration of degraded land and water resources

- widespread development of more sustainable agricultural practices

- reduction of carbon emissions from human activities

- greater environmental and resource management of other land use industries, such as mining

- greater control over urban development and the spread of cities that are encroaching onto farming land.

These challenges are going to be difficult in light of present trends in both industry and human development. Some of these trends are the increasing demand for biofuel production in the developed economies of the world as they seek alternative (renewable) sources of fuel. The biofuel industry, which converts organic products such as corn or sugar cane to fuel, is competing with food agriculture for the use of arable land.

The demand is being driven by the increasing cost of oil and the need for countries to secure energy resources while there is political instability in the oil-producing nations of the world.

Another trend that is going to put enormous pressure on global agriculture is the growth of the middle class in places such as China and India.

As these nations become more prosperous, the demands on food production change. In the past, the levels of calorie consumption in these countries have been well below the levels of Western nations such as Australia and the United States, and their diets have been based on staple foods such as rice.

However, as prosperity increases dietary habits change, and levels of consumption increase. One of the areas of consumption increase is animal protein products such as meat and dairy. As it takes much more energy and resources to produce a kilogram of meat than it does to produce a kilogram of rice, the extra demands on agricultural production are going to be enormous.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 4.12

- Examine how successful Australian agriculture has been in meeting the food and fibre requirements of its population.

- Explain what ‘food security’ means.

- Referring to Source 4.39, identify the areas of Australia that will be prone to severe salinity in 2050.

- Explain how this distribution corresponds to existing areas of agricultural production.

- Summarise the impact salinity may have on future Australian food production.

RESEARCH 4.6

- Research biofuel and how it is impacting on agricultural food production.

- The UN Food and Agriculture Organization was set up to deal with issues of world hunger. The logo of the FAO (Source 4.38) is instantly recognisable. Inset in a circle which represents the globe are the letters of the organisation and the image of a stalk of wheat. It also has the Latin phrase fiat panis, meaning ‘Let there be bread’. Create a logo for an organisation that has been set up to deal with issues of food security in Australia over the next 40 years. Annotate your logo, explaining your choice of words, phrases and images. Have a class vote on which one best represents the future of Australian agriculture.