4.1 Agriculture in Australia

Sustained agriculture first developed over 12 000 years ago in various regions around the globe.

This first Agricultural Revolution marked a monumental shift from the early hunting and gathering societies to communities that domesticated animals and grew crops for food. The advent of sustained agriculture was a relatively recent phenomenon in Australia. Prior to European settlement the Indigenous people of Australia lived a predominantly nomadic hunting and gathering existence and did not farm the land in a systematic way. The arrival of the First Fleet in January 1788 heralded the arrival of agriculture. In May 1788 the livestock in the fledgling colony was listed as seven horses, seven cattle, 29 sheep, 74 pigs, five rabbits, 18 turkeys, 29 geese, 35 ducks and 209 chickens, and a few acres of land were being cultivated (unsuccessfully) for cereal crops at Farm Cove.

By 1860 the agricultural revolution had firmly arrived. On the official Census there were listed 431 525 horses, 3 957 915 cattle, 20 135 286 sheep and 351 096 pigs, and 48 000 hectares of land was devoted to cereal crops.

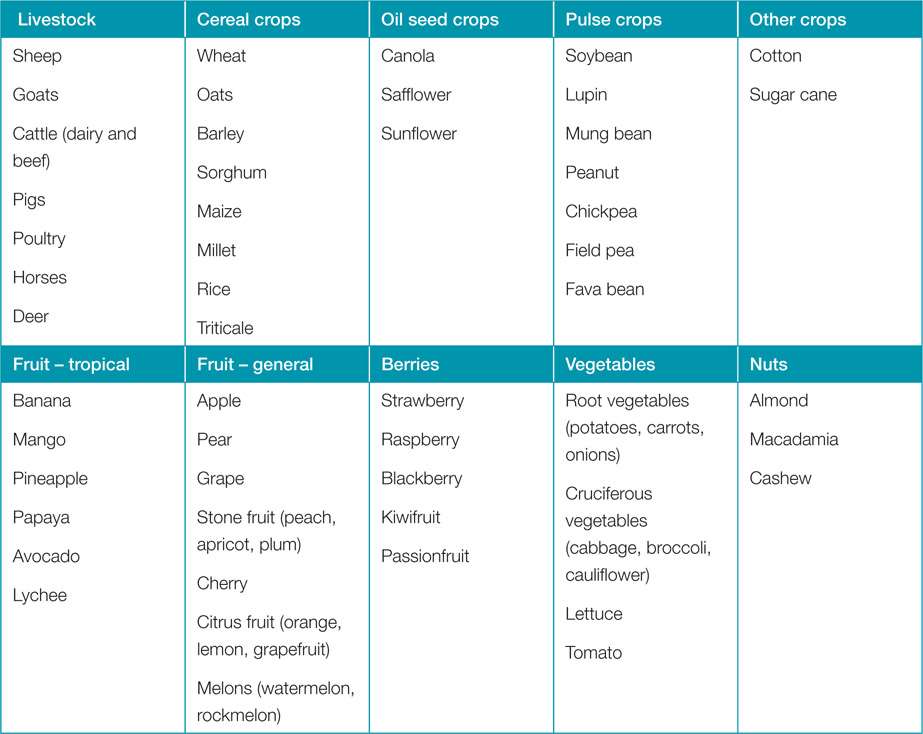

Today the agricultural industry extends right across the nation, except in the desert areas in Australia’s vast inland, and encompasses an enormous range of commodities, as shown in the table below.

These industries range in size from the extensive cattle stations – which can be up to 24 000 square kilometres in Australia’s arid zone – to fruit and vegetable farms of just a few hectares in the peri-urban zones.

| Livestock | Cereal crops | Oil seed crops | Pulse crops | Other crops |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sheep Goats Cattle (dairy and beef) Pigs Poultry Horses Deer |

Wheat Oats Barley Sorghum Maize Millet Rice Triticale |

Canola Safflower Sunflower |

Soybean Lupin Mung bean Peanut Chickpea Field pea Fava bean |

Cotton Sugar cane |

| Fruit - tropical | Fruit - general | Berries | Vegetables | Nuts |

| Banan a Mango Pineapple Papaya Avocado Lychee |

Apple Pear Grape Stone fruit (peach, apricot, plum) Cherry Citrus fruit (orange, lemon, grapefruit) Melons (watermelon, rockmelon) |

Strawberry Raspberry Blackberry Kiwifruit Passionfruit |

Root vegetables (potatoes, carrots, onions) Cruciferous vegetables (cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower) Lettuce Tomato |

Almond Macadamia Cashew |

-

Source 4.1 One of the world’s major cereal crops is wheat. The wheat in this image has reached maturity and is ready for harvesting. -

Source 4.2 Cattle mustering on a Northern Territory cattle station

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 4.1

- The products in the list above are only some of the agricultural commodities that are produced in Australia. The list doesn’t include silage production for animal feed, for instance. As a class, discuss some of the other agricultural products that you are familiar with that are grown in Australia.

- Some of the commodities on the list, such as cattle, can be produced in most Australian regions, but some have specific growing or production conditions. As a class, make a list of some of the major factors that may have an influence on where agricultural production can take place and what types of commodities can be produced.

- As a class, discuss the importance of agriculture to the Australian economy relative to other sectors of the economy, such as mining, manufacturing or services. Which is most important, and why?

RESEARCH 4.1

Agricultural productivity in Australia is constrained by significant geological and climatic factors, as well as pressures from alternative land uses such as urban development. Of all the inhabited continents, Australia is the driest. It also has some of the Earth’s oldest, shallowest and most weathered and infertile soils, making vast areas of Australia unsuitable for intensive agriculture. Over 70% of Australia’s land area receives low amounts of rainfall and is classed as either semi-arid or arid: of the 7.6 million square kilometres of total land area barely a tenth is suitable for sown crops and pastures, and much of that only after the addition of fertilisers or the use of other soil-improving practices such as the planting of pasture legumes (which fix essential nitrogen to the soil). Australia does have areas of naturally fertile soil, such as in the Wimmera area of Victoria and the Darling Downs region of Queensland, but these are not extensive compared with the deep, fertile soils of the North American prairies or the Ukraine in Eastern Europe.

Australia is also one of the most urbanised countries in the world, with almost 90% of the population living in towns and cities, and most of these within 100 kilometres of the coast along the southwestern, southern and eastern regions of the continent, where the soils are more fertile and rainfall is more abundant. The continual spread of urbanisation is one of the pressures that agriculture is facing in Australia, as more and more land is being claimed for urban development.

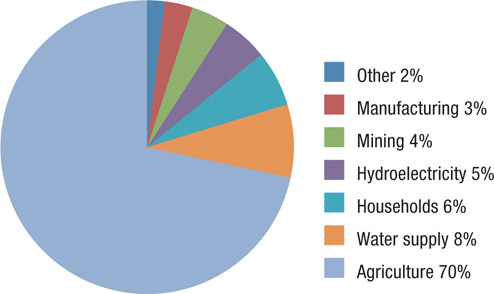

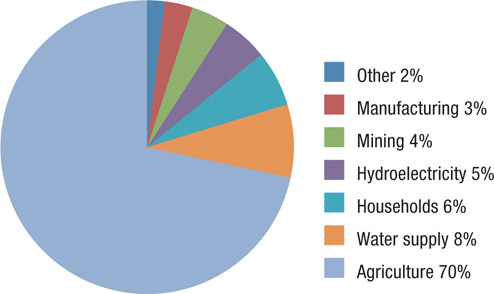

Land and water are essential for agriculture and the Australian landscape and water catchments have changed significantly since European settlement. Agriculture is the largest consumer of water in Australia – on average, it represents 50–70% of total water use – and since settlement around 100 million hectares of forest and woodland have been cleared, mostly for agricultural production. Even today land continues to be cleared for agriculture. In 2013 around 456 million hectares, or 59% of land in Australia, is used for agriculture, making it the dominant form of land use.

Agricultural land use has also had other significant impacts on the Australian environment.

The alteration of vegetation cover has led to increased erosion and salinity; land clearing has caused a reduction in biodiversity and increased extinction rates; the cultivation of food plants and the grazing of domestic animals have changed the nutrient balance of the soil; and the addition of fertilisers has increased the rates of soil acidification.

Historically, despite the difficulties faced in establishing and adapting agriculture to Australian conditions, and in managing the impacts agriculture has had on the environment, it has been a successful enterprise. Australian farmers are innovative. They are constantly adopting new ideas and practices to increase productivity while also looking after the land. They have been able to produce enough food and natural fibre (such as wool and cotton) to meet the needs of several times our own population.

Agricultural enterprises are also successful for the Australian economy. Until the 1970s agricultural products made up a substantial percentage of world trade. In 1876–80, food and natural fibre accounted for about 58% of the value of world trade. This made Australian farmers some of the wealthiest in the world and this wealth showed in the grandeur of some of the houses built at the time.

Some of the longest fences in the world have been created in Australia to protect farming land and livestock from pests and predators. The Dingo Fence, which is 5400 kilometres long – 2.5 times the length of the Great Wall of China – stretches from South Australia to Queensland to protect sheep from dingo attack.

One of these, Werribee Park Mansion in Melbourne’s west, was built by the pastoralists Andrew and Thomas Chirnside in the 1870s and reflected the immense wealth the family had made from sheep production.

Today agriculture makes up less than 10% of world trade and farm profits have decreased significantly. Today’s Australian farmers need to produce more than four times the volume to earn, in real terms, just over half of what farmers earned in 1951–52.

Rabbits, which were released in Victoria in 1859 and soon grew to plague proportions, have had a devastating impact on the natural environment and agricultural production. To protect their crops from rabbits, farmers in Western Australia erected three rabbit-proof fences. Rabbits managed to cross the first one, so two more had to be constructed. The total length of all three fences is more than 3000 kilometres.

Source 4.5a Tony Mayo, Operations Manager, talks about the Dingo Fence. (02:17)

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 4.2

Agriculture and the spread of settlement in Australia

The spread of settlement in Australia was closely linked to the expansion of agriculture. This was not always an easy process. For the first 150 years of settlement the establishment of agriculture was hampered by the vastness of the continent, the unfavourable climate and rainfall, the poor soil, the lack of agricultural experience and knowledge of those settling the land and poor decision making by farmers and Australian governments.

Despite being a nation that has largely settled the coast, the bush has always been a feature of the Australian collective consciousness, and dreams of making a living from the land have had a strong attraction for many people.

In the process of settlement the landscape was fragmented. Before the arrival of Europeans in 1788, the Indigenous peoples were intimately bound to the land; it was – and still is – an essential part of their spiritual and physical being.

European notions of land ownership didn’t exist and territorial boundaries between peoples were based on cultural identification with land features such as rivers and mountains. Aboriginal people could move freely over the landscape.

European notions of land ownership were based on the principle of private ownership, and land was allocated with geometrical precision, based on units such as acres. The fragmentation of the landscape begun by the Europeans was consolidated with the establishment of boundary fences and roads which clearly marked out territory and restricted the free passage of people and animals through the landscape. Widespread land clearing was an integral part of this process.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 4.3

RESEARCH 4.2

In a recent book by the historian Bill Gammage, called The Biggest Estate on Earth, he claimed that the Indigenous people of Australia were the first to create widespread landscape change on the continent and were adept managers of the land who intimately understood the life cycles of native plants and the importance of fire in the management of the landscape. Gammage’s conclusions imply that contemporary Australian land managers have a lot to learn from Indigenous land management techniques. Research what some of these Indigenous land management techniques were and how they might be useful in contemporary land management practices.

Settlement and expansion 1788–1860

From early in the history of the Australian colonies the colonists eagerly sought new land for growing cereal crops and for sheep and cattle production.

The period from 1788 to 1820 was a period of limited agricultural expansion because of low population growth and geographical impediments such as the impenetrability of the mountain ranges west of Sydney. Most of the agricultural settlement was taking place within 50 kilometres of Sydney in New South Wales and at Hobart and Launceston in what was then called Van Diemen’s Land. Wheat and maize were the major crops and wool was only beginning to be recognised as having economic potential.

Once a crossing had been found through the Blue Mountains west of Sydney in 1813, settlers who were eager for fertile land for agricultural development spread through the inland. The same thing was happening in Victoria. In 1836, Sir Thomas Mitchell, who was exploring the western district, wrote of the richness of the land.

Towards the south coast on the south and adjacent to the open downs between the Grampians and Port Phillip, there is a low tract consisting of very rich black soil, apparently the best imaginable for the cultivation of grain in such a climate.

Agricultural settlement of the vast interior of the continent during the next 40 years was led by the squatters, who were seeking land for sheep and cattle grazing. The growing of cereal crops was still largely restricted to the high rainfall coastal zones on Australia’s eastern and south-eastern coasts.

The squatters were farmers who had, during the early years of European settlement, illegally occupied large areas of Crown land. So vast was the country and so small was the population that there was little the colonial authorities could do to keep the squatters in check.

The vast sheep and cattle runs the squatters acquired – they averaged about 12 000 hectares – were so financially successful that these men became wealthy and powerful members of Australian society: the squattocracy. By the 1830s, colonial governments no longer regarded the squatters as acting illegally and began granting them licences or leases for the territory that they had occupied.

Source 4.7 Pattern of land settlement in Australia

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 4.4

- Explain why the development of agricultural settlement in Australia was so limited in the first 20 years of European settlement.

- Discuss whether or not it was in the interests of the squatters to ignore the government restrictions on taking up land to run sheep and cattle.

- Suggest ways in which the success of the wool industry might have promoted greater migration to the Australian colonies.

Unlocking the land – turning the bush into farms, 1860–1900

By the 1860s the colonial governments were under pressure to ‘unlock’ the land that had been occupied by the squatters and break it up into farming allotments. A number of factors were encouraging this change:

- Large numbers of immigrants had swelled the population of the colonies following the gold rushes of the 1850s and there was pressure on governments to allocate land to these new settlers.

- The governments of the colonies also believed that Australia’s fortunes could not be tied predominantly to the export of wool and decided that the rapidly growing population needed to be self-sufficient in food.

- There was a general (but inaccurate) belief that the European tradition of intensive farming of smaller parcels of land could be transplanted to Australian conditions.

Colonial governments introduced a number of Land Acts (laws) which broke up the land holdings of the squatters and promoted schemes aimed to help people farm a variety of produce on their land, with a particular emphasis on intensive agriculture such as wheat rather than extensive agriculture such as wool production. There was great enthusiasm for these schemes: it was hoped they would revolutionise agricultural production in Australia. One government land agent in Echuca in Victoria even enthusiastically wrote in 1872 that the Victorian Land Act had somehow affected the climate:

With the Land Act 1869 a great improvement in the seasons took place, the rainfall increased, the grass became abundant, steady and increasing settlement took place, which has now amounted to a rush, and … still they come. (quoted in Charles Fahey, John Sweeney and the Making of an Australian Farming Landscape: A Micro-level Study of Baulkamaugh and Katunga, 1877–1955)

Large areas of land which had previously been licensed to squatters was divided into selections of 16–130 hectares and sold. In Victoria, the Land Act of 1862 reserved 4 million hectares of land for selection. In many cases the wealthy squatters, through various means, were able to buy back much of their land, often selecting the most productive allotments.

Many of the blocks that were not good quality agricultural land or did not have characteristics essential for viable farming, such as creeks and rivers, were rejected by the squatters and were bought by small farmers known as selectors.

The selectors who purchased these land parcels brought their families to live and work on the farms, and for a great number of these families extreme hardship ensued. Many of these blocks were too small to sustain a family, let alone produce a surplus, and a great number of them had no access to a reliable water source. Drought and flood caused heartbreak for many, and attempts to get the land to produce enough to sustain a family often had adverse environmental consequences.

Large numbers of these farms were doomed to failure and over time many were deserted by the farmers, who just walked off the land. The land parcels were then often incorporated back into larger land holdings.

It was during this period that the agricultural landscape of Australia started to change dramatically. Close to the major settlements of Melbourne and Sydney, which had been settled for a number of years, smaller agricultural holdings were well established – land had been cleared and fenced and roads had been built. Large parts of the interior, however, had not been substantially changed. The squatters had had little need to clear the land of vegetation and fence it. The boundaries of their land holdings were creeks and rivers or other prominent landscape features.

The various Land Acts of the 1860s brought about a significant change in land use to areas that had previously been open pastoral land. The Land Acts generally required the selectors to clear and fence their land, and this and other provisions in the Acts were beginning to change the characteristics of land use in Australia.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 4.5

- List the ways in which the Land Acts of the 1860s were a failure.

- Describe how the Land Acts of the 1860s promoted change in the landscape of Australia’s inland.

- One of the underlying beliefs driving agricultural settlement in Australia in the first 150 years was a belief in the ideal of the ‘yeoman farmer’. The yeoman farmer was a European small farmer who, with intensive labour, could work a small plot of land and make it productive. Many people came to Australia from Europe with the belief that they could make a similar living from the land here. In what ways did this belief not quite fit the reality of Australian conditions and circumstances?

Consolidation of agricultural settlement, 1900–70

By the first decades of the twentieth century virtually the whole of the Australian continent had been opened up to agriculture and agriculture was a major employer. In 1910 agricultural industries employed about 26% of the Australian workforce.

The only areas which didn’t have an agricultural presence were the deserts in central Australia.

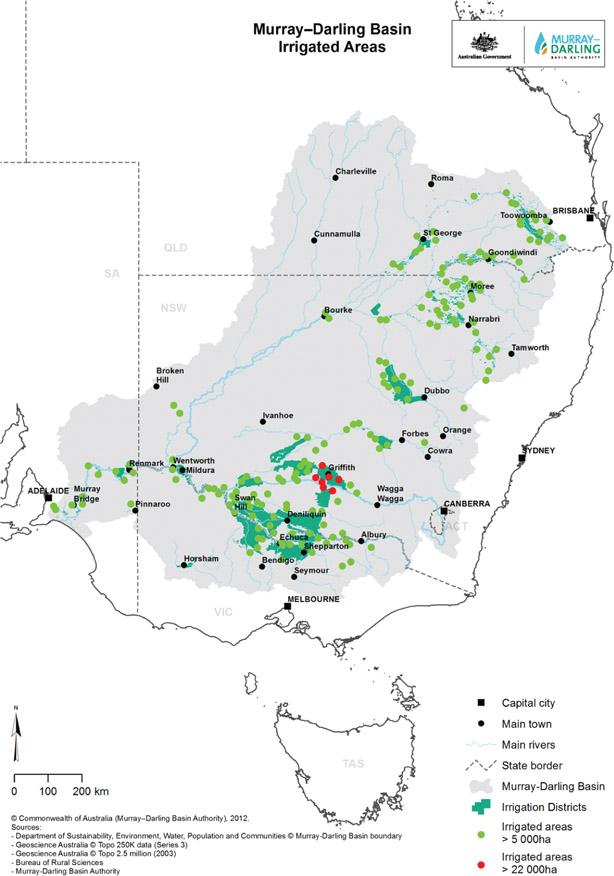

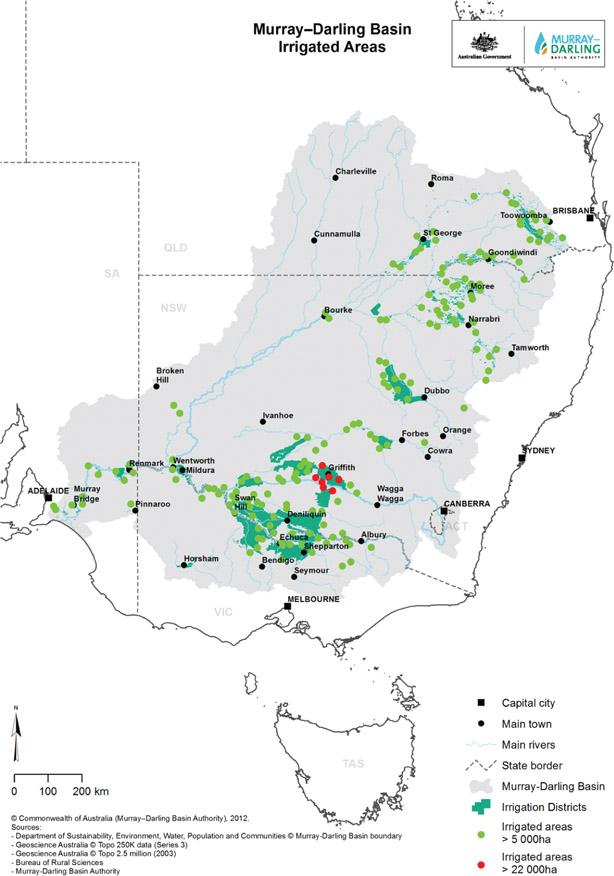

Agricultural activity was widespread and varied. While the dryland production of wool and wheat were the mainstays of the Australian agricultural industry, irrigation schemes had also been established, mostly along the Murray River and its tributaries, to support more intensive agricultural practices such as fruit growing and dairying.

A pastoral industry based on cattle grazing had been established across Australia’s northern regions, from the Kimberley Ranges in Western Australia to the Gulf of Carpentaria in Queensland.

Sugar cane and bananas were being harvested along Queensland’s tropical coast. Tasmania was producing quality apples, and a dairy industry was established in the high-rainfall zones along Australia’s south-east and southern coasts.

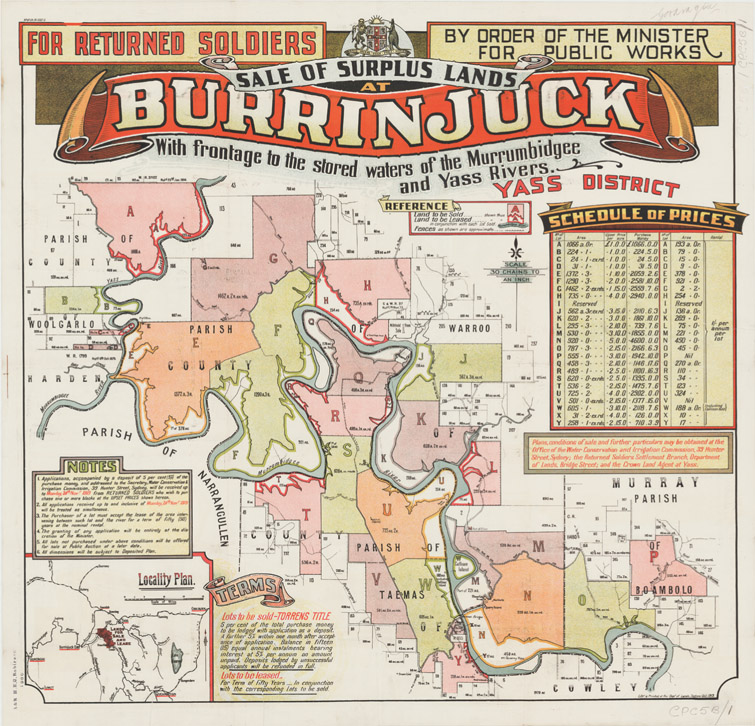

Systematic agricultural settlement in Australia was further developed in the first half of the twentieth century through the establishment of ‘soldier settlement schemes’ to repatriate men returning from World Wars I and II.

Australian governments, faced with having to provide for tens of thousands of men returning from war, developed various land settlement schemes to place these men and their families on farming allotments. These schemes served a number of purposes:

- They rewarded men for their war service.

- They solved the problem of finding employment for these men.

- They were seen as a means of boosting agricultural production through intensive farming practices.

Like the Land Acts of the 1860s, the soldier settlement schemes broke up the bigger landholdings and opened up various tracts of Crown land for settlement. State governments also spent substantial amounts of money buying land that was already privately owned.

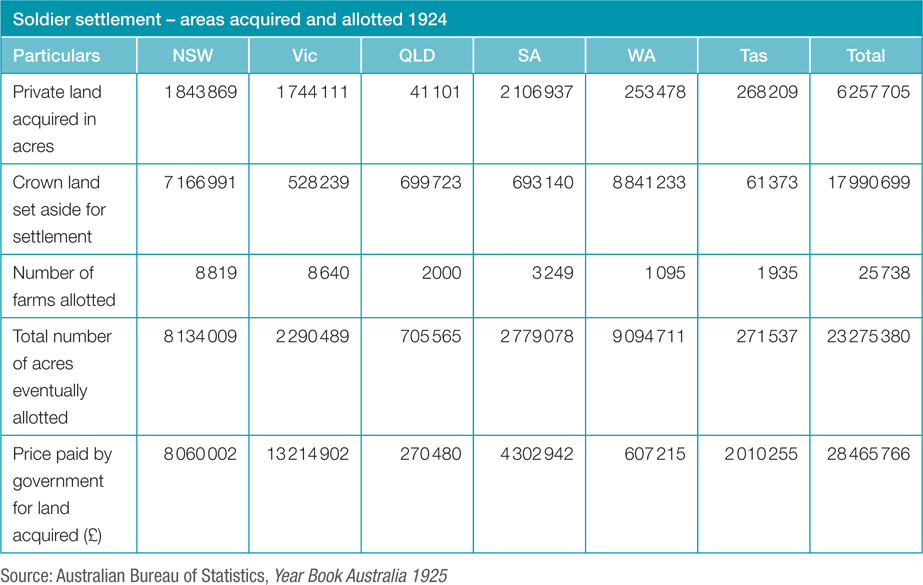

The table below shows the amount of land acquired by each of the state governments for their soldier settlement schemes, how much was allotted and how much the acquisition of private land cost.

Like many of the government rural settlement schemes that had come before it, the soldier settlement scheme set up in 1918 following World War I was also generally regarded as unsuccessful, and many of these soldier settlers had left the land within 20 years. In Victoria, 60% of the settlers had left their blocks by 1939.

| Soldier settlement - areas acquired and allotted 1924 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Particulars | NSW | Vic | QLD | SA | WA | Tas | Total |

| Private land acquired in acres | 1 843 869 | 1 744 111 | 41 101 | 2 106 937 | 253 478 | 268 209 | 6 257 705 |

| Crown land set aside for settlement | 7 166 991 | 528 239 | 699 723 | 693 140 | 8 841 233 | 61 373 | 17 990 699 |

| Number of farms allotted | 8819 | 8640 | 2000 | 3249 | 1095 | 1935 | 25738 |

| Total number of acres eventually allotted | 8 134 009 | 2 290 489 | 705 565 | 2 779 078 | 9 094 711 | 271 537 | 23 275 380 |

| Price paid by government for land acquired (£) | 8 060 002 | 1 321 4902 | 270 480 | 4 302 942 | 607 215 | 2 010 255 | 28 465 766 |

| Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Year Book Australia 1925 | |||||||

There were a number of reasons for the failure of these farms:

- Many of the soldiers were inexperienced as farmers.

- The soldiers did not have enough money or resources to develop their farms.

- Many of the blocks were too small to generate sufficient income and a number of them were situated in areas that were not suited to intensive agriculture.

- The prices farmers were getting for their produce fell.

The soldier settlement schemes which followed World War II, in 1945, were generally regarded as more successful. By the middle of the century the conditions required for successful agricultural enterprises in Australia were better understood, so soldiers were allocated blocks of land of an appropriate size, and the type of agriculture that took place on them was more in accordance with what the land could sustain.

By the last decades of the twentieth century the large pastoral estates of the nineteenth-century squatters throughout southern Australia had largely been broken up. The modern equivalents of these enormous pastoral stations are now found across the arid and semi-arid regions of Australia, where cattle and sheep grazing over large areas is the only viable form of agricultural production.

The unproductive blocks of land that had brought such hardship to settlers following the Land Acts of the 1860s and the soldier settlement schemes of the early twentieth century were gradually bought and incorporated into larger, more productive farms or incorporated into nature reserves.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 4.6

The limits of agricultural production in Australia

One of the major factors influencing the history of agricultural settlement in Australia for over 150 years after 1788 was a lack of understanding of the climatic and geological limitations on agricultural production. Agricultural knowledge and practices imported from Europe and other agricultural regions of the world did not suit Australia’s conditions, and agricultural adaptations to Australian conditions were often learned through harsh trial and error. The social impacts of some of these ill-suited beliefs and practices were disastrous for farming families, and they have also caused long-term damage to Australia’s environment, damage that will affect future food production.

Australia’s unique climate

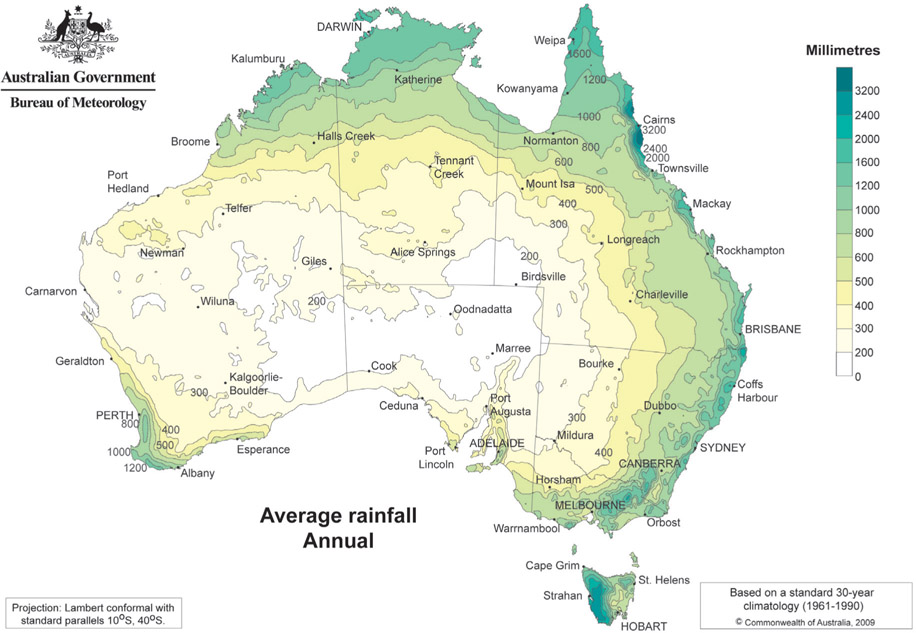

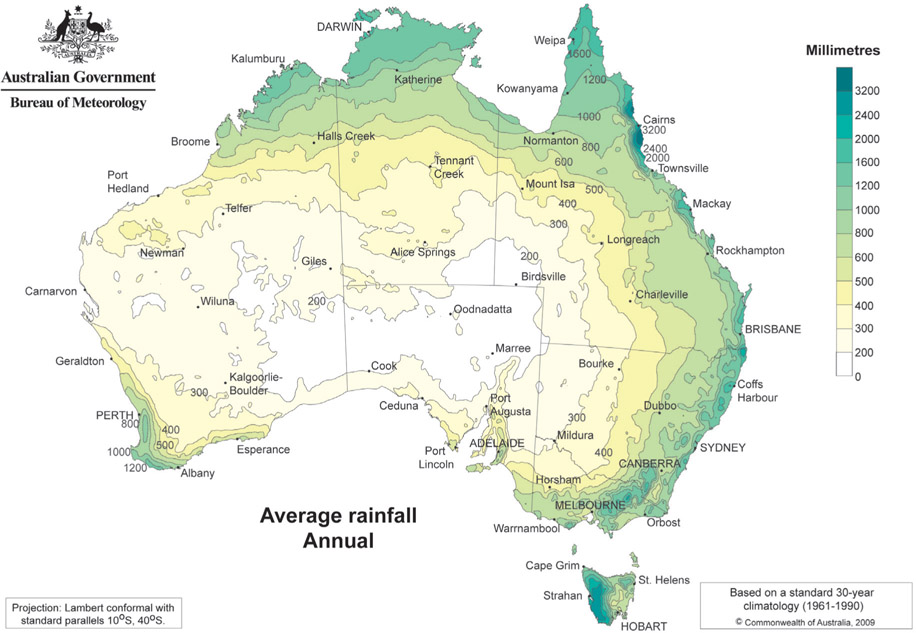

Rainfall, or the lack of it, is the most important single factor determining agricultural land use in Australia, but knowledge about how Australian rainfall patterns impact on agricultural land use was accumulated only over time.

The Australian continent experiences a high degree of climatic seasonality: it fluctuates between periods of rain and periods of dry conditions.

Vast areas of the continent receive limited rainfall, and even across large areas that do receive good rainfall, high rates of evaporation cause the ground to quickly dry out, depriving plants of moisture.

Much of Australia’s interior receives little rainfall in either winter or summer, and experiences high evaporation rates. Many of these areas are only suitable for extensive livestock grazing.

Even the northern half of Australia, which receives higher rainfall rates than the arid interior, receives this rain in the summer months when evaporation is at its greatest, limiting the type of agriculture than can be practised there. In the Kimberley region in northern Western Australia, for example, the number of livestock that the land is capable of sustaining is only one head of cattle for every 25–30 hectares. Agricultural production in these arid and semi-arid areas in the past has at times exceeded the land’s capacity, causing serious land degradation. Erosion and destruction of fragile habitats have resulted from overgrazing and poor crop choices. In some areas government decrees limited the types of agricultural practices that could be used. The Goyder Line in South Australia, for example, was drawn up in 1865 to limit the extent of wheat production in the north of the state.

The southern portion of the continent, through New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia and Western Australia, receives most of its rainfall during the cooler winter months, when evaporation rates are lower. This makes these areas more suitable for a greater variety of agricultural enterprises, as soil moisture is generally sufficient to grow cereal crops even in relatively dry land such as the Mallee area of northern Victoria. This region also includes most of Australia’s sheep belt.

RESEARCH 4.3

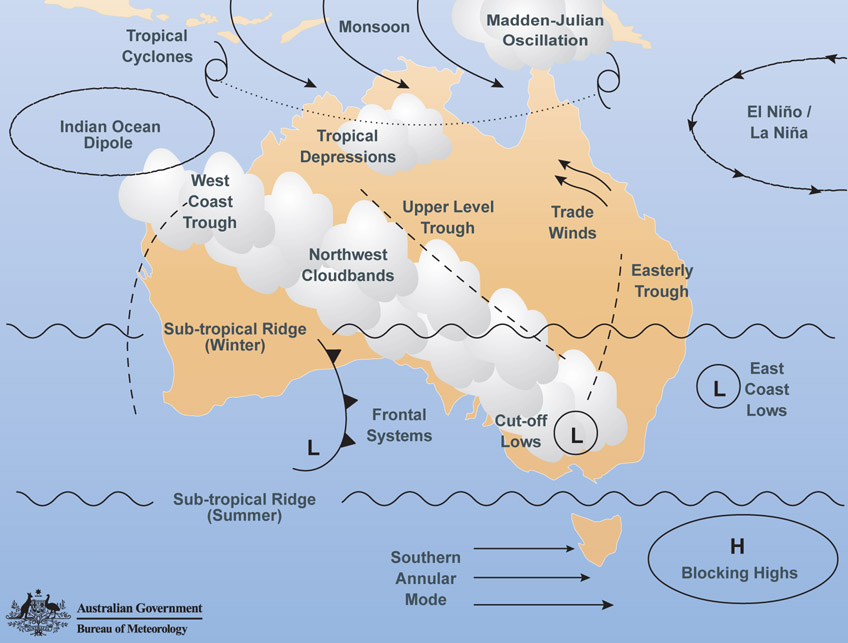

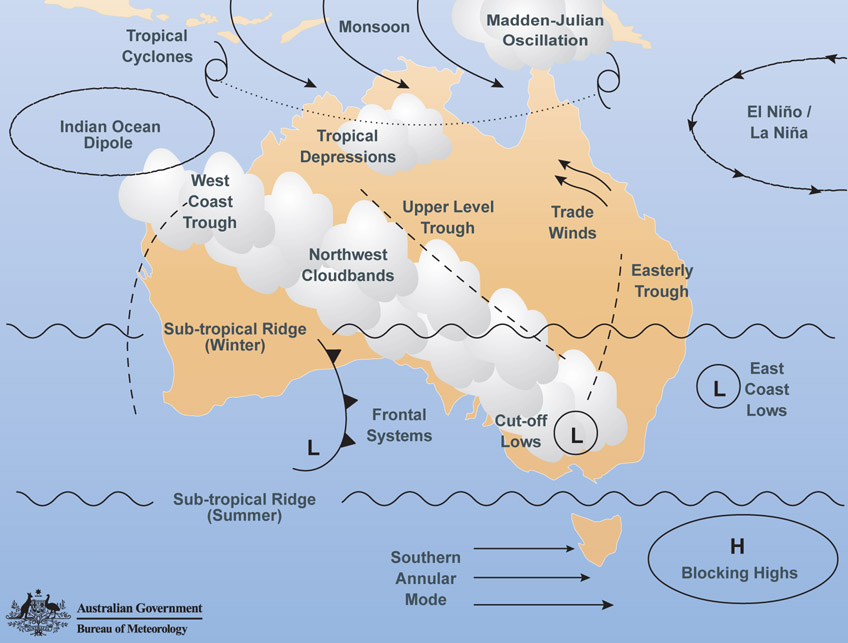

- Source 4.13 shows the climate influences that affect the Australian continent. Use the links at www.cambridge.edu.au/hass9weblinks to go to the Australian Bureau of Meteorology website and detail how each of these influences affects the weather.

- Research the historical climate and rainfall data for your area. Starting at www.cambridge.edu.au/hass9weblinks again, link to the Australian Bureau of Meteorology website.

Along the left-hand side of the home page is a series of links. Go to Climate and Past Weather. On this page you need to click on the link for weather and climate data. To get information for your area you need to:- select ‘Monthly Rainfall’ or ‘Monthly Temperature’

- select a weather station in the area of interest (by typing in the name of your location).

- Describe the climate in your area: hot summer/cold winter; mild summer/mild winter; winter rainfall/dry summer; uniform rainfall all year round.

- Investigate the Goyder Line. What factors were used to determine it?

Australia’s agricultural zones

The CSIRO has identified 11 agricultural regions in Australia, based on soil type, land features, climate and ecology, as shown in Source 4.14.

Source 4.14 The 11 agricultural ecological zones as defined by the CSIRO