3.4 A closer look at rice in Southeast Asia

Rice is the staple food of Southeast Asia and contributes significantly to the livelihoods of smallholder farmers, the regional economy and society. Rapidly increasing populations in the countries of Southeast Asia have placed pressure on the rice-farming sector to both increase yields for food and income security and to strive towards sustainable practices to protect water, soil and other environmental resources. Rice accounts for two-thirds of the calorie intake of more than 3 billion people in Asia and it is increasingly consumed in Europe, North America and other regions. Approximately 610 million people in Southeast Asia depend on rice as a staple food.

The role of rice

Rice as a staple food

In Southeast Asia, rice is consumed daily and is considered to be the most important cereal crop for both food and income security.

After maize, rice is considered the second most important crop in the world. However, maize is also grown for biofuel, and rice has greater importance as a staple food.

Rice production is widely considered the reason for populations in Southeast Asian countries continuing to grow with less poverty. Rice is also increasingly consumed in Europe, North America, Australia and New Zealand because of immigration and the increasing interest in food from other regions. Rice is also consumed in Africa, the Middle East and Pacific countries.

The Green Revolution

Rice production increased dramatically in Southeast Asia in the 1960s because of the introduction of high-yielding varieties (HYVs) and improvements in fertilisers, pesticides and farm machinery. Financial institutions and governments all played a role in financing the uptake of new technologies by providing credit or donating inputs to smallholder farmers. By the 1970s, more than 40% of rice farms involved irrigation, and by the 1980s, HYVs were being widely used. This dramatic, technology-driven increase in rice production was dubbed ‘the Green Revolution’ and was responsible for a decline in poverty and an increase in economic growth.

The rice plant

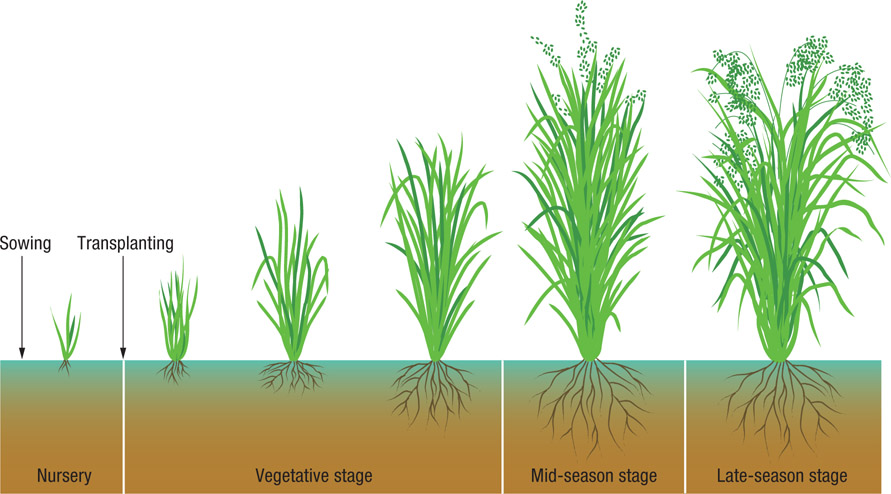

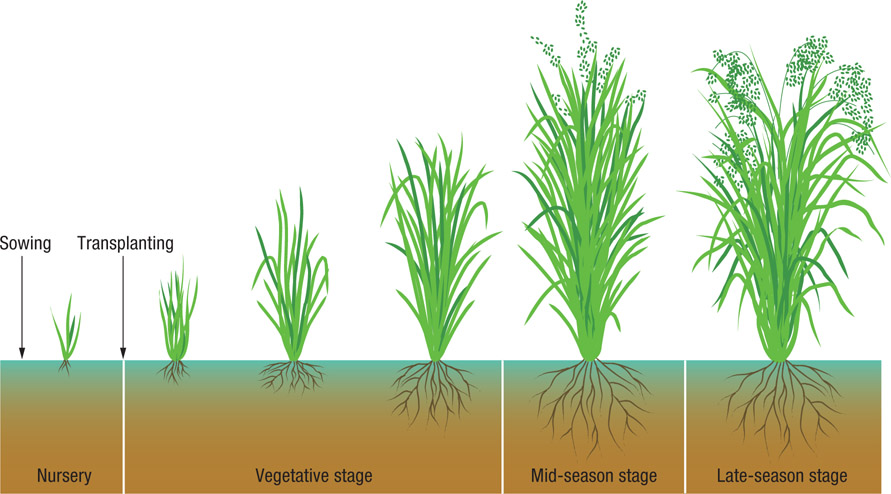

Source 3.27a The rice plant (02:17)

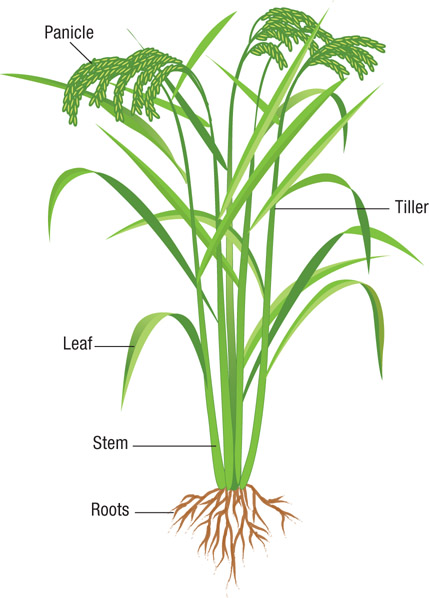

The rice plant is a monocot grass that can grow to 1.8 metres tall.

Many varieties are less than 1 metre tall. The term ‘rice’ is used for the seed or grain of the rice plant, but is often used more generally, and incorrectly, to describe the whole plant. A tiller is a shoot made up of the roots, a stem and leaves. The term ‘tillering’ refers to the division of tillers from the root zone during the vegetative phase. A panicle is a cluster of rice flowers from which the grain develops. HYVs often have more panicles than older varieties of rice. Panicles form in the reproductive stage and remain present in the ripening stage when the rice grain becomes fully formed.

The rice plant depends on nitrogen, phosphate and trace nutrients to grow. It also has a high water requirement.

Nutrients are supplied by the soil and water the rice grows in, but domesticated varieties of rice must be supplemented with nutrients from fertilisers to produce their maximum yield. There are four main stages in rice plant growth:

- nursery stage – this stage begins with sowing rice seeds in nursery fields. Seedlings are transplanted approximately one month after sowing.

- vegetative stage – following transplanting, the rice plant develops tillers, and later the panicle growth begins.

- mid-season stage – this is a reproductive phase during which the panicle develops flowers. Nutrient and water requirements are high during this phase.

- late-season or maturing stage – this is when seeds develop from fertilised flowers. The seeds are ready for harvest when they are firm. If seeds are not harvested in time, they become ‘overripe’ and fall from the plant.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 3.8

Significance in culture

In many Southeast Asian societies, rice farming is celebrated through festivals and ceremonies.

These events are important because they bring rice-farming communities together and maintain cultural traditions that encourage social cohesion.

Many rice festivals and ceremonies have remained relatively unchanged for centuries and help to preserve song and dance traditions. Spiritual beliefs that predate current religious practices underpin many of these ceremonies and are accepted as part of the rich cultural history of Southeast Asian countries.

Rice was once widely used as currency in Southeast Asia and other parts of the world. It was used as currency until World War II in some rural areas.

Rice-based food is given as gifts during religious events and on holy days. The end of the Holy Month of Ramadan (Eid al-Fitr) is celebrated with gifts of rice-sweets and elaborate meals centred around rice. In Malaysia and Indonesia, which are largely Islamic countries, rice has a special place during Ramadan as well: it is prepared for the early morning meal and the ‘breaking of fasting’ in the evening. Rice sweets and rice-based foods also feature strongly in Buddhist, Hindu and Christian celebrations. Malay peoples, who live in Indonesia, Brunei, Singapore and Malaysia, celebrate Tepuk Tepung Tawar (Patting Plain Flour Ritual) in which different coloured rice grains, along with flowers, vegetables and flour, represent aspects of happiness and prosperity.

Rice-growing systems

Irrigated rice

Over 70% of rice is produced in small (0.5–2.0 hectares) irrigated rice fields. This involves the diversion of water from canals and streams into rice fields where water is maintained at a depth of 5–10 centimetres. Between 3 and 6 tonnes of rice per hectare (per crop) are produced, but up to 10 tonnes per hectare can be achieved. Most irrigated rice fields are in the lowlands, where the topography is better suited to water management. Water is retained in rice fields using small dykes called bunds. Farmers remove small sections of these bunds to release water into neighbouring fields or to drain the fields for the rice harvest. Irrigated rice fields are usually used for rice monoculture – up to three crops can be grown per year in the wet tropics. In temperate areas, only one rice crop is grown per year, and other crops such as wheat are grown in rotation.

Source 3.29l Ray and Edna Montalo farm irrigated rice on Luzon Island in the Philippines. (04:47)

Rain-fed rice

Rain-fed rice farming depends on rainfall as its primary source of water. There are two sub-categories of rain-fed rice farming: lowland and upland. Rain-fed lowland farming involves the use of bunds to flood the rice field. The coastal lowlands used for rain-fed rice farming are often subject to prolonged episodes of flooding and drought. During these droughts, salinity can become a problem as saline tidal waters, which have high evapotranspiration rates, flow into low-lying fields.

Rain-fed lowland rice farming is challenging for farmers because of climatic variability and because the soils are often unsuitable. Because of the risk of crop failure, many farmers are reluctant to invest in farm inputs such as fertiliser and tend to avoid HYVs, which demand more water and nutrients. The risk of economic loss from floods or drought is too high for most farmers. As a result of minimising their investment in farm inputs, they usually produce less than 2 tonnes of rice per hectare.

Rain-fed upland rice farming is also known as dryland cropping. In this system, bunds are not used to submerge rice, and lower-yielding rice varieties that require less water are generally used. Because yields are often less than 1 tonne per hectare, rice is only farmed to meet local food requirements. Other crops are grown along with rice to provide cash crop alternatives.

Rice production and sustainability

Environmental impacts

The Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change (IPCC) estimates that methane emissions from rice farming are approximately 15% of the total emitted by all sources. The release of methane into the atmosphere contributes to the overall human-induced Greenhouse Effect. Methane is mainly produced in rice fields when they are submerged: ponded waters prevent atmospheric oxygen from entering the soil, leading to an increase in the methane-producing anaerobic bacteria that thrive on decomposing plant material, manure and nitrogen-based fertilisers.

Source 3.31 Methane gas production in rice fields is enhanced by the use of fertiliser and manure, and by waterlogged conditions. (01:44)

Irrigated rice requires more water than most other cereal crops. This high demand reduces the water available to the natural environment and creates competition with other land uses that share water resources.

Irrigation canals and bunds are designed to direct fresh water away from natural watercourses and into the rice-farming areas. The impact of water diversion is most significant in the dry season in monsoonal environments. During the wet season, monsoon rains provide abundant water, but during the dry season, water availability can be limited. In temperate rice-growing areas, where annual rainfall is generally lower, there is pressure on water resources year-round.

Fertilisers are not fully utilised by rice plants, so any excess is absorbed by the soil, lost into the atmosphere, leached into groundwater or transported offsite by runoff or the release of bunded waters. Fertilisers can therefore lead to eutrophication of waterways: they can reduce the concentration of dissolved oxygen in the soil, which leads to reduced biodiversity and degraded habitat.

HYVs are more susceptible to insect pests than older rice varieties. The use of pesticides is controversial because of concerns over human health risks, and about their effects on the natural environment. Pesticides may affect insects and other fauna that are important for ecosystem functioning. Pesticides are readily transported by water and can affect aquatic ecosystems many kilometres away from their source.

A great deal of land clearing is done to create more rice fields. Land clearing reduces the size of natural environments and can increase erosion and offsite sedimentation. Pressure on land resources from urbanisation, industry and other farming practices has led to the reclamation of coastal wetlands for rice. These reclaimed lands are often not well suited to rice farming because of their low elevation, the presence of acid sulfate soils and their proximity to tidal waters. Reclaimed wetlands can easily be exposed to flooding, and to salinisation and acidification of soil and water.

Rural–urban migration

Rural–urban migration is a threat to the supply of labour for rice-producing rural areas. Economic growth in Southeast Asia since the 1980s has attracted rural youth to secure, salaried positions in the cities and the increasingly urbanised regional centres.

The migration of young people to urban areas has left behind an ageing labour force in rice-farming communities. Rice farms are often handed down through generations, so a lack of interest in maintaining the family-run farm forces owners to sell their fields or to lease them to others, which means the family tradition of rice farming can cease abruptly.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 3.9

Environmental constraints

The success of rice farming is inextricably linked to the environment. Without adequate water supply and fertile soil, rice farmers face the challenge of artificially managing the environments they farm.

To achieve high yields from HYVs, they have to increase their use of fertilisers, pesticides, water and other inputs.

Rainfall is the primary water source for farmers. Keeping water in upstream areas, in large dams and weirs, and diverting water to other land uses and domestic supply, reduces the availability of water in irrigated rice-farming areas. Surface waters (rivers, streams, canals and lakes) are also at risk of contamination from domestic waste and effluent from industry.

Soil fertility is variable across Southeast Asia. Nutrient-rich soils are found in alluvial environments, such as flood plains, and in areas where volcanic activity occurs. Hill slope soils, which are often used for rice terraces, can be shallow and low in nutrients. Sandy soils in coastal areas are often low in nutrients due to leaching.

The disturbance of acid sulfate soils in coastal lowlands can release large amounts of acid and toxic metals, which harm the rice plant and can degrade the offsite environment.

Changing consumption trends

Southeast Asian countries can be categorised as net importers or net exporters of rice. Globalisation and an increase in the disposable income of young people have led to a shift in food preferences.

Urban youth are increasingly adopting Western diets and replacing rice with wheat-based staples, such as bread.

The health benefits of reducing carbohydrates, which are a major component of rice, are also better known. A change in dietary preferences has reduced the consumption of rice by individuals, but the rising population maintains the demand for rice, particularly in rural areas where incomes are lower and traditional diets remain important.

Factors that determine whether a country is a net exporter or a net importer include: the number of people who consume rice, the available labour source, the land available for cultivation, the yield of the rice varieties that can be farmed, the farming technology and seasonal controls (such as rainfall) on production. Countries may shift from being net importers to net exporters and vice versa if there is a change in any of these factors.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 3.10

Investigate the role of pests and how they are controlled in rice fields. Information is widely available on the internet.

Complete the following tasks:

- Identify three pests that affect rice fields.

- Describe how these pests affect rice production.

- List control measures that are used to manage or eradicate these pests.

- Identify the environmental risks of the control measures.