2.8 Factors affecting Australian biomes

Climate has been identified as the main factor affecting the global distribution of biomes.

Examining biomes at a larger scale allows for the closer examination of other factors which affect the distribution of biomes on a more local scale.

Mountain ranges

The pattern of biomes along Australia’s east coast is influenced by the location of the Eastern Highlands, or the Great Dividing Range. This set of mountains, even though it is not high by world standards, has an orographic impact on the circulation of wind and the accompanying rainfall. Winds blowing in off the ocean are forced to rise, and they drop their moisture on the eastern side of the range. Source 2.21 and Source 2.22 show the effects of this. The sources show a narrow coastal vegetation pattern and a different vegetation pattern immediately to the west of the range.

Ocean currents

The other impact on biomes which can be found by examining biomes at a larger scale is that of ocean currents. Source 2.35 shows Australia’s ocean currents.

Source 2.35 Australia’s oceanic currents (02:25)

What needs to be examined is where the currents are coming from, as this affects the temperature of the water and therefore the temperature of the air above them. The Eastern Australian Current (EAC) is a warm current. It flows from north to south along the east coast of Australia. This warm current will warm the air above it, causing it to expand. As air expands, it can absorb more molecules of water, so the air moving across this current towards the Eastern Highlands holds lots of moisture.

This is compressed when the air cools as it rises over the Eastern Highlands. The result is simple: lots of rainfall on the eastern side of the Eastern Highlands and much less on the western side.

On the other side of the continent the situation is more complex. The western side of Australia does not have a clear annual oceanic flow. The South Equatorial Current (SEC) is blocked by currents flowing north from Antarctica. These waters are much colder, and they also have an effect on the air flowing over them. Cold air does not pick up moisture from the ocean and so is unlikely to bring rain. As the air passes over the land it is warmed, and is therefore able to absorb moisture, making rain even less likely.

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 2.9

Seasonal air mass movements

Monsoons

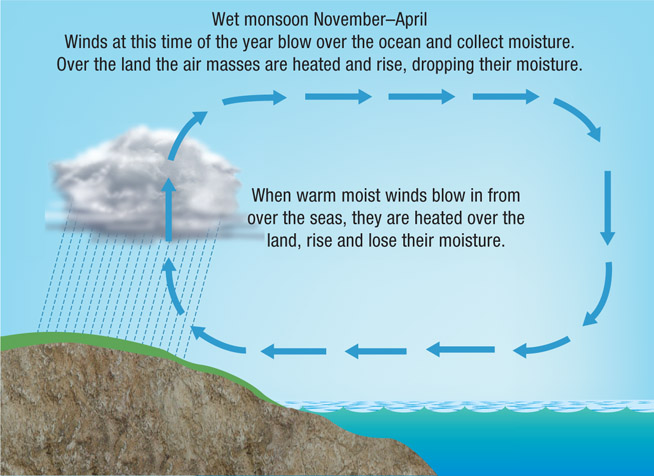

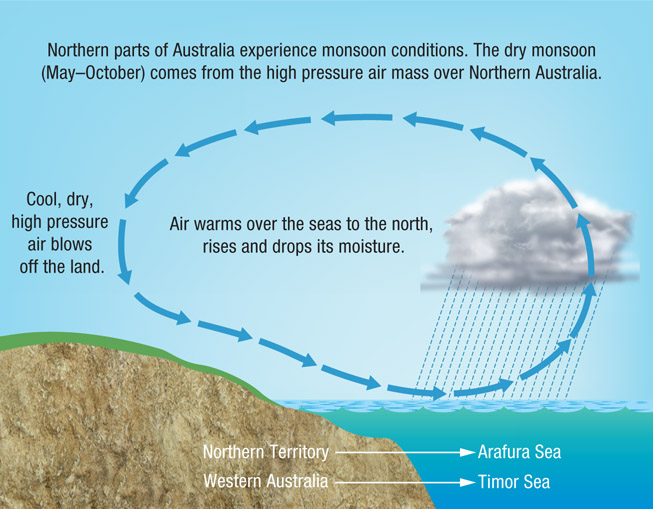

Northern Australia experiences a seasonal change in weather as Earth’s changing location in relation to the sun makes the sun appear to move north and south of the Equator. Air masses are affected by this: areas of low pressure move north as the sun appears to move north (to the Tropic of Cancer) and south as it appears to move south (to the Tropic of Capricorn). This affects the biomes in this part of Australia.

When the sun appears to be over Australia’s Tropic of Capricorn, it warms up the land there and causes the air above it to rise. This rising air draws in moisture from the surrounding sea bodies and rainfall occurs. This promotes growth, especially of the grasses of the savanna areas of northern Australia. This is the time of the ‘wet’ monsoon.

When the sun appears to be over the Tropic of Cancer, in the Northern Hemisphere, low pressure air moves northwards and dry, stable, high pressure air takes its place over the Australian continent. This high pressure air comes from central Australia; it does not contain moisture and is cold, and so it descends. The dry period begins, and continues until the sun again appears to be over the Tropic of Capricorn. Sources 2.36 and 2.37 show how this seasonal change operates.

El Niño and La Niña

Weather patterns associated with El Niño and La Niña events may have more unpredictable impacts on biomes. The monsoons are an annual event, but El Niño and La Niña weather events can last much longer.

These events can bring flooding rain, or crippling drought, to northern and eastern Australia.

They are predictable, which is of great help to Australian farmers: they can work out when to plant their wheat crop and when to expect rain to start the crop. However, the duration and intensity of these events are not so predictable.

They are driven by air mass movements generated by cold ocean currents flowing north along the coast of South America. If the flow of the current is strong, eastern Australia will experience a La Niña wet weather pattern; if the current is weak, eastern Australia will experience an El Niño dry weather pattern.

Source 2.38 El Niño and La Niña weather patterns (01:42)

DEVELOPING YOUR UNDERSTANDING 2.10

- Explain why vegetation cover, rather than the amount of rain that falls in a year, should be used as the method of identifying a desert area.

- Analyse the similarities and differences between how plants and animals cope with desert conditions.

- Explain how monsoons affect Australia’s biomes.

- Examine how El Niño and La Niña events affect Australia’s vegetation patterns.